Trucking in Cameroon

The road to hell is unpaved

Dec 19th 2002 | DOUALA

From The Economist print edition

The Economist rides an African beer truck—and gets a lesson in development economics

WITH 30,000 bottles lashed firmly to the back, the beer truck pulled out of the factory yard. Or rather, it tried to. The lunchtime traffic in Douala, Cameroon's muggy commercial capital, was gridlocked, as usual, and no one wanted to let a 60-tonne lorry pull out in front of them.

Fortunately the driver, Martin, had been trucking for 19 years, and could manoeuvre the 18-wheeled beast with skill and calculated aggression. After several minutes of inching threateningly forward, he managed to barge out into the fast lane, where the truck immediately had to stop. As far as the eye could see, stationary cars and buses blocked the way.

Considering that Douala is one of Africa's busiest ports, handling 95% of Cameroon's exports and also serving two landlocked neighbours, Chad and the Central African Republic, the poverty of the city's infrastructure is a bit of a problem.

The roads are resurfaced from time to time, but the soil is soft and the foundations typically too shallow. Small cracks yawn quickly into wide potholes. Street boys fill them with sand or rubble, and then beg for tips from motorists. But their amateur repair work rarely survives the first rainstorm.

Besides the potholes, motorists must dodge the wrecks of cars that have crashed. Under Cameroonian law, these may not be moved until the police, who are in no hurry, have arrived. It took our truck half an hour to reach the first petrol station, and another half an hour to fill up, owing to arguments about paperwork. Another hour and two police road-blocks later, we finally left the city. That was the end of the easy part of the journey.

Hard trucking

Visitors from rich countries rarely experience the true ghastliness of third-world infrastructure. They use the relatively smooth roads from airports to hotels, and fly any distance longer than a hike to the curio market.

But the people who actually live and work in countries with rotten infrastructure have to cope with the consequences every day. These are as profound as they are malign. So to investigate how bad roads make life harder, this correspondent hitched a ride on a beer truck in Cameroon, a pleasant, peaceful and humid country in the corner of the Gulf of Guinea.

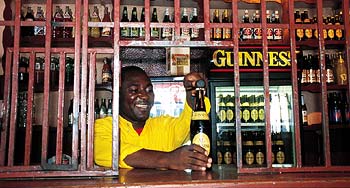

The truck belonged to a haulage firm that makes deliveries for Guinness Cameroon, a local subsidiary of the multinational that makes the eponymous velvety black beer, which is popular in Ireland, Britain—and West Africa.

The plan was to carry 1,600 crates of Guinness and other drinks from the factory in Douala where they were brewed to Bertoua, a small town in Cameroon's south-eastern rainforest. As the crow flies, this is less than 500km (313 miles)—about as far as from New York to Pittsburgh, or London to Edinburgh. According to a rather optimistic schedule, it should have taken 20 hours, including an overnight rest. It took four days. When the truck arrived, it was carrying only two-thirds of its original load.

The scenery was staggering: thickly forested hills, stretching into the distance like an undulating green ocean, with red and yellow blossoms floating on the waves. Beside the road were piles of cocoa beans, laid out to dry in the sun, and hawkers selling engine oil, tangerines, and succulent four-metre pythons for the pot. We were able to soak up these sights at our leisure: we were stopped at road-blocks 47 times.

These usually consisted of a pile of tyres or a couple of oil drums in the middle of the road, plus a plank with upturned nails sticking out, which could be pulled aside when the policemen on duty were satisfied that the truck had broken no laws and should be allowed to pass.

Sometimes, they merely gawped into the cab or glanced at the driver's papers for a few seconds before waving him on. But the more aggressive ones detained us somewhat longer. Some asked for beer. Some complained that they were hungry, often patting their huge stomachs to emphasise the point. One asked for pills, lamenting that he had indigestion. But most wanted hard cash, and figured that the best way to get it was to harass motorists until bribed to lay off.

At every other road-block, the policemen checked to see whether the truck was carrying a fire extinguisher. The driver's mate, Hippolyte, would have to climb down and show the device to a policeman reclining in the shade of a palm tree, who would inspect it minutely and pore over the instructions on the side. Similar scrutiny was lavished on tail-lights, axles, wing-mirrors and tyres, all in the name of road safety. Oddly, no one asked about seat belts, which Cameroonians wear about as often as fur coats.

At some road-blocks, the police went through our papers word by word, in the hope of finding an error. The silliest quibble came from a frowning thug who declared that this correspondent's visa was on the wrong page of his passport. The longest delay came in the town of Mbandjok, where the police decided that Martin did not have enough permits, and offered to sell him another for twice the usual price. When he asked for a receipt, they kept us waiting for three-and-a-half hours.

A gaggle of policemen joined the argument, which grew heated. The total number of man-hours wasted, (assuming an average of seven policemen involved, plus three people in the truck), was 35—call it one French working week. And all for a requested bribe of 8,000 CFA francs ($12).

The pithiest explanation of why Cameroonians have to put up with all this came from the gendarme at road-block number 31. He had invented a new law about carrying passengers in trucks, found the driver guilty of breaking it, and confiscated his driving licence. When it was put to him that the law he was citing did not, in fact, exist, he patted his holster and replied: “Do you have a gun? No. I have a gun, so I know the rules.”

Mud, inglorious mud

Even without the unwelcome attentions of the robber-cops, the journey would have been a slog. Most Cameroonian roads are unpaved: long stretches of rutty red laterite soil with sheer ditches on either side. Dirt roads are fine so long as it does not rain, but Cameroon is largely rainforest, where it rains often and hard.

Our road was rendered impassable by rain three times, causing delays of up to four hours. The Cameroonian government has tried to grapple with the problem of rain eroding roads by erecting a series of barriers, with small gaps in the middle, that allow light vehicles to pass but stop heavy trucks from passing while it is pouring. This is fair. Big trucks tend to mangle wet roads.

The barriers, which are locked to prevent truckers from lifting them when no one is looking, are supposed to be unlocked when the road has had a chance to dry. Unfortunately, the officials whose job it is to unlock them are not wholly reliable. Early on the second evening, not long after our stand-off with the police in Mbandjok, we met a rain barrier in the middle of the forest. It was dark, and the man with the key was not there. Asking around nearby villages yielded no clue as to his whereabouts. We curled up in the hot, mosquito-filled cab and waited for him to return, which he did shortly before midnight.

The hold-up was irritating, but in the end made no difference. Early the next morning, a driver coming in the opposite direction told us that the bridge ahead had collapsed, so we had to turn back.

Six hours, 11 more road-blocks and three sardine sandwiches later, we arrived in Yaoundé, the capital, where Guinness has a depot. The alternative route we had to take to get to Bertoua meant passing a weighing station, where vehicles over 50 tonnes face steep tolls. Since we were 10 tonnes overweight, Martin needed permission to offload 600 crates. But it was a Saturday, the man in charge was reportedly at lunch, and we did not get permission until the next morning. It then took all morning to unload the extra crates, despite the fact that the depot was equipped with excellent forklifts. After 25 hours without moving, we hit the road again, and met no road-blocks for a whole 15 minutes.

For much of the rest of the journey, which took another 17 hours, this correspondent was struck by how terrifying Cameroonian roads are. Piles of rusting wrecks clogged the grassy verges on the way out of Yaoundé. We saw several freshly crashed cars and a couple of lorries and buses languishing in ditches. None of the bridges we crossed seemed well-maintained. And when we arrived in Bertoua, we heard that two people had been crushed to death on a nearby road the previous day, when a logging truck lost its load on to their heads.

Coping with chaos

Cameroonian roads have wasted away. In 1980, there were 7.2km of roads per 1,000 people; by 1995, the figure had shrunk to only 2.6km per 1,000. By one estimate, less than a tenth are paved, and most of these are in a foul condition.

In recent years, however, aided by a splurge of World Bank money, things have improved a bit. Douala, once considered one of the worst ports on earth, has been substantially rehabilitated since 2000. A lot has been done to improve the roads around Douala in the last two years, says Brian Johnson, the managing director of Guinness Cameroon. The Cameroonian government no longer takes three years to approve plans for roadworks.

But there is much work still to be done, and firms still have to find ways to cope with horrible highways. Guinness used to buy second-hand army trucks, which was a false economy, because they kept breaking down. Now, it buys its lorries new from Toyota, with which it has a long-term agreement to ensure that it will always be able to get hold of mechanics and genuine spare parts (as opposed to fake or stolen ones, which are popular in Cameroon, but of variable quality). The firm is also making more use of owner-drivers, who have a greater incentive to drive carefully.

“Just-in-time” delivery is, for obvious reasons, impossible. Whereas its factories in Europe can turn some raw materials into beer within hours of delivery, Guinness Cameroon has to keep 40 days of inventory in the factory: crates and drums of malt, hops and bottle tops. Wholesalers out in the bush have to carry as much as five months' stock at the start of the rainy season, when roads are at their swampiest. Since they tend to have shallow pockets, Guinness often gives them exceptionally easy credit terms.

Out in the forest, the firm does whatever it takes to get beer into bars and bottle stores. It is an exercise in creative management. At the depot in Bertoua, crates are unloaded from big lorries and packed into pick-up trucks, which rush them to wholesalers in small towns. The wholesalers then sell to retailers and to small distributors, who ferry crates to villages in hand-pushed carts, on heads and even by canoe.

No matter how hard Guinness tries, however, the bars that sell its brew sometimes run dry. Jean Mière, a young bar-owner in a village called Kuelle, complained that he had nothing to sell to his thirsty customers because the local wholesaler's driver was in jail. Yves Ngassa, the local Guinness depot chief, was incensed. He had arrived in an empty pick-up truck, having been given directions by the wholesaler who normally supplied Mr Mière, but the wholesaler had not mentioned that Mr Mière had no beer, nor asked if he could load some into Mr Ngassa's empty pick-up.

In all, bad infrastructure adds about 15% to costs, reckons Mr Johnson. But labour costs are low, Cameroonians drink a lot of beer, and Guinness's main competitor, Société Anonyme des Brasseries de Cameroun, faces similar hurdles. Despite the unusual management challenges, Guinness runs a healthy business in Cameroon, its fifth-biggest market by volume after Britain, Ireland, Nigeria and America. Its return on capital in Cameroon is around 16%, and sales of its main brands have grown by 14% a year over the past five years. The big losers from lousy infrastructure are ordinary Cameroonians.

How bad roads hurt the poor

Roads in rainforests are a bad thing, argue many environmentalists. They facilitate illegal logging and destroy indigenous cultures by bringing them into contact with aggressive, disease-carrying, rum-swilling outsiders. But the absence of roads probably hurts the poor far more.

The simplest way to measure the harm caused by bad infrastructure is to look at how prices change as you move away from big cities. A bottle of Coca-Cola, for example, costs 300CFA in Yaoundé, where it is bottled. A mere 125km down the road, in the small town of Ayos, it is 315CFA, and at a smaller village 100km further on, it is 350CFA. Once you leave the main road, prices rise sharply. A Guinness that costs 350CFA in Douala will set you back 450CFA in an eastern village that can be reached only on foot.

It was worth the wait

It was worth the waitWhat is true of bottled drinks is also true of more or less any other manufactured good. Soap, axe-heads and kerosene are all much more expensive in remote hamlets than in the big cities. Even lighter goods, which do not cost so much to transport, such as matches and malaria pills, are significantly dearer.

At the same time, the stuff that the poor have to sell—yams, cassava, mangoes—fetch less in the villages than they do in the towns. Yet, thanks to poor roads, it is hard and costly to get such perishable, heavy items to market. So peasant farmers are doubly squeezed by bad roads. They pay more for what they buy, and receive less for what they sell. Small wonder that the African Development Bank finds “a strong link between poverty and remoteness”.

The UN's International Fund for Agricultural Development estimates that African villages with better physical infrastructure produce one-third more crops per hectare than those with poor infrastructure, enjoy wages 12% higher, and pay 14% less for fertiliser. And no country with good roads has ever suffered famine.

Where roads improve, incomes tend to rise in parallel. One study estimated that each dollar put into road maintenance in Africa would lower vehicle maintenance costs by $2-3 a year. In Cameroon, where the soil is wondrously fertile, farmers start growing cash crops as soon as nearby roads are repaired. Big commercial farmers benefit too. Along the highway to Douala lie great plantations of sugar cane, and banana trees whose fruit is wrapped in blue plastic bags, to keep at bay the birds and bugs that might mar the visual perfection demanded by European consumers.

Where roads are left to deteriorate, women bear the heaviest burden. According to the World Bank, a typical Ugandan woman carries the equivalent of a 10-litre (21-pint) jug of water for 10km every day, while her husband humps only a fifth as much. With better roads, both men and women can, if nothing else, hitch rides on lorries, thereby sparing their feet and getting their goods more swiftly to market.

The famished road

Sometimes, people find ingenious ways around infrastructure bottlenecks in Africa. Buses designed for European roads do not last long in Nigeria, so Nigerians import the chassis of heavy European lorries and mount locally manufactured bus bodies on top. This is much cheaper than importing a whole lorry, and more durable than an imported bus. Locals also simply adapt. In parts of Cameroon where there is no electricity to power a refrigerator, people drink their beer—and indeed any other liquid—warm.

But there is no substitute for building and maintaining better infrastructure. In some areas, such as telecoms, private firms will do the work if allowed to. Thanks to private investment, mobile telephones have spread throughout Africa with the pace and annoying chirrups of a swarm of locusts. In Cameroon, Guinness now finds it much easier to contact employees than it did a couple of years ago, although the firm also frets that mobile telephones are gobbling up scarce disposable income that might otherwise be spent on beer.

The private sector does not, however, spontaneously provide roads, because the beneficiaries cannot easily be charged. Tolls can meet some of the cost of maintaining highways, but it is hard to squeeze money out of peasants on feeder roads.

The World Bank estimates that at least $18 billion needs to be pumped each year into African infrastructure if the continent is to attain the sort of growth that might lift large numbers of people out of poverty. Investment currently runs at less than a third of this. In the current economic downturn, private companies in the West are in no mood to rush into risky investment, least of all in Africa. The gap can only be filled, the Bank reckons, by governments and foreign donors.

In short, the governments of poor countries ought to pay more attention to their roads. A good first step in Cameroon would be to lift those road-blocks and put the police to work repairing potholes.