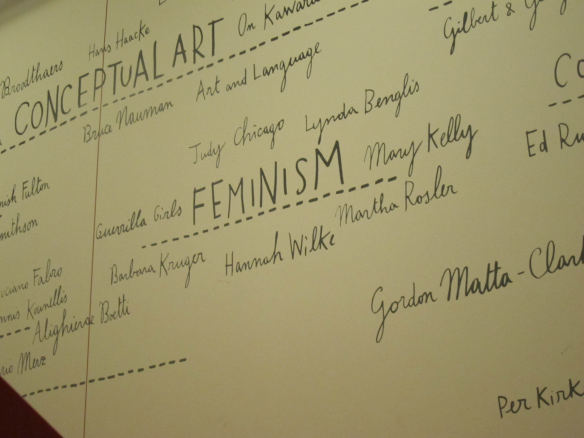

Following Amelia Jones, this course “takes feminism seriously but does not seek to patrol its borders by, for example, labeling authors or producers of images ‘feminist’ or ‘not feminist.” This course challenges a standard institutionalization of feminist art, as evidenced by the Tate Modern timeline, as something contained in a white, US-based, 1970s past. It understands this version as an impoverished vision that blocks our understanding of feminist art as a much more expansive field of creative practice and critical interpretation with important roots in other communities and parts of the world. Feminist art is not over and done; it is alive and flourishing, challenging institutionalized hierarchies of art, raising questions about how we see and and make meaning of what we see, influencing image making practices, and making different futures imaginable.

T 03.31 Course overview

Film Screening: Lynn Hershman Lesson, W.A.R. Women Art Revolution (83 min.)

We watched this film on the first day of class with the following questions in mind:

What story of feminist art does this film tell? What theme, idea, story, person, or artwork from the film made an impression on you? Why?

If you missed the film, please watch it in the UW Libraries Media Center (Suzzallo Library, 3rd floor) where it is on reserve. You should ask for it by the title and the call number DVD ZF 077.

Th 04.02 What is feminism? What is art/visual culture?

bell hooks, Feminism Is for Everybody, “Introduction,” “Feminist Politics,” “Consciousness Raising,” “Feminist Class Struggles,” “Global Feminism,” and “Race and Gender”

bell hooks, Art on My Mind: Visual Politics, “Introduction: Art Matters,” “Art on My Mind”

Cynthia Freeland, But Is It Art?, “Blood and Beauty,” “Cultural Crossings”

Key feminist concepts discussed:

- bell hooks’s definition: “Feminism is a movement to end sexism, sexist exploitation, and oppression.”

- gender equality (reform) vs. systemic change (revolution)

- feminisms as multiple, as a movement open to critique and challenge in order to remain committed to a vision of justice

- intersectional analysis: analyzing systems of oppression not just along single vectors but as operating in a matrix; challenging false universals (like “woman”); understanding one’s own positionality and politics of location; theorizing about practical problems

- sex/gender system: as one that naturalizes and makes normative connections between sex and the social construct of gender; that requires critique and deconstruction in order undo the hierarchies it makes seem natural

- queer (as a noun and a verb)

“Feminism,” Timeline of Modern and Contemporary Art, Tate Modern, London, 2012, photo: Sonal Khullar

]]>By the end of the quarter, you will be able to explode this whiteboard timeline with many other vectors that trace artists and artworks in ways that move us beyond this limited conception of feminist art. See also the Sackler Center for Feminist Art timeline, an expanded but still largely Western-centric chronology. What will you add to these timelines with your own coursework? You are part of this larger project of creative and critical practice!

- What is the difference or relationship between art and visual culture?

- What is feminist viewing?

- What is the relationship between people and things? What is the social life of art as a thing?

- How have feminist scholars of art critiqued dominant stories of art that marginalize women, artists of color, and non-western artists?

- What methods have they used? What have been the successes and pitfalls of these methods?

- What dominant story of feminist art has emerged in recent decades? Who and what does it marginalize? At what cost to our understanding of feminism and art?

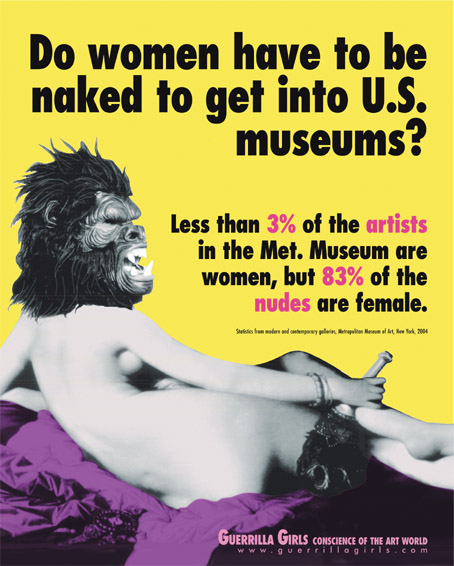

- Following the Guerrilla Girls’ line of questioning (see below), do women have to be Western to get into textbooks of feminist art?

Th 04.07 What is feminist art?

Amelia Jones, The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader, “Introduction: Conceiving the Intersection of Feminism and Visual Culture”

Rosemary Betterton, The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader, “Feminist Viewing: Viewing Feminism”

Arjun Appadurai, “The Thing Itself”

Cynthia Freeland, But Is It Art?, “Money, Markets, Museums”

Begin browsing The Guerrilla Girls’ Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art

Th 04.09 Exploding Canons

Presentation: Sage Ross (Wiki Education Foundation) introduction to Wikipedia Art + Feminism course page: Moved to next T 04.14

The Guerrilla Girls’ Bedside Companion to the History of Western Art

Cynthia Freeland, But Is It Art?, “Gender, Genius, and Guerrilla Girls”

Whitney Chadwick, Women, Art, and Society, “Worlds Together, Worlds Apart”

Handouts: Visual Analysis Paper + Wikipedia Gap Analysis

We will watch the following short video about the Art+Feminism project to begin thinking about the Wikipedia Gap Analysis assignment and to prepare for Sage Ross’s visit to class on Tuesday, April 14. For more information, see the links page.

]]>Yayoi Kusuma & Yoko Ono

Feminist consciousness in Japan has drawn inspiration from women’s movements in other parts of the world and has been forged as part of the development of a specific form of modernity. How can the lives and works of Yayoi Kusama and Yoko Ono be understood through this local-global feminist relationship?

What were the social, historical conditions that laid the ground for their travels between Japan and New York? How did they struggle for recognition in both Japanese and US art worlds? Why have they been left out of histories of the New York and Japanese avant-garde art movement?

When and how have they been included in histories of feminist art?

In her book Into Performance, Midori Yoshimoto uses the term “intermedia” (not to be confused with mixed media or multi-media) to refer to art that blurs the border between art media and life media, that breaks down, in other words, distinctions between art and life. How do Yayoi Kusama and Yoko Ono do this in their art? How might their intermedia art be interpreted as feminist?

T 04.14

Presentation: Sage Rose (Wiki Education Foundation)

Vera Mackie, Feminism in Modern Japan: Citizenship, Embodiment and Sexuality, “Introduction”

Midori Yoshimoto, Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York, “Performing the Self: Yayoi Kusama and Her Ever-Expanding Universe”

Th 04.16

Midori Yoshimoto, Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York, “The Message Is the Medium: The Communication Art of Yoko Ono”

DUE: Visual Analysis Paper

]]>The ultimate goal for me is a situation in this society, where ordinary housewives visiting each other and waiting in the living room, will say, “I was just adding some circles to your beautiful de Kooning painting.” – Yoko Ono, 1967

Pushpamala N & Navjot

In “Feminist Forms, International Exhibitions, and the Postcolonial Woman Art,” Sonal Khullar writes, “The marginalization in this essay [Marsha Meskimmon’s essay on mapping 1970s feminist art globally] of nonwestern artists, postcolonial artists, and artists of color…suggests a larger structural problem in the way the history of feminist art is narrated in Western museums and classrooms.” What kinds of contextualization does she suggest are necessary for a deeper understanding of the artwork that Geeta Kapur writes about in “Gender Mobility: Through the Lens of Five Women Artists in India”? How can greater contextual knowledge shift our understanding of feminism, of art, and of feminist art?

Does the brief history of women’s moments and feminism in India in Radha Kumar’s introduction to The History of Doing help you understand the work of Pushpamala N. or Navjot in ways you might not have grasped otherwise?

What kinds of interventions is Pushpamala making in her photographic re-performances of various images from the past?What kind of archive is she creating through her use of archival materials?

How do Pushpamala’s artworks explore the idea of performativity?

What do you think is feminist about the collaborative art of Navjot in Bastar? What power dynamics are involved in collaborative art?

T 04.21

Presentation: Nina Bozicnik (Assistant Curator) & Emily Zimmerman (Associate Curator of Programs) of the Henry Art Gallery about Upcoming Exhibits, the Henry’s Collection Study Center, and Feminist Exhibit Making

Radha Kumar, The History of Doing: An Illustrated of Movements for Women’s Rights and Feminism in India, “Introduction”

Sonal Khullar, “Feminist Forms, International Exhibitions, and the Postcolonial Woman Artist,” Journal of the Korean Association for the History of Modern Art

Geeta Kapur, “Gender Mobility: Through the Lens of Five Women Artists in India,” Global Feminisms

Th 04.23

Geeta Kapur, “Navjot Altaf: Holding the Ground,” Asia Art Archive

Grant Kester, The One and the Many: Contemporary Collaborative Art in a Global Context, “The Genius of Place,” 76-95

Pushpamala N with Clare Arni, Native Women of South India: Manners and Customs: Jayalithaa, manual photographic print on metallic paper, 2002-03

For further viewing:

Beyond the Self: Pushpamala N

Pushpamala N discusses the inspiration for the Abduction series which was on display in the National Portrait Gallery exhibition Beyond the Self.

Zanele Muholi & Tracey Rose

How can photography function as a technology of discipline, as well as a form of expressive resistance to histories of discipline, control, and invisibility? How does Zaneli Muholi use photographic portraiture in relation to or against the identifying photograph in Apartheid-era South African passbooks? (How might you compare Muholi’s response to the colonial legacy of photography with that of Pushpamala’s?)

How does the history of institutionalized racism under Apartheid continue to influence the LGBTI/Q community in the new South Africa? (See for example the video below that documents unrest during the 2012 Gay Pride parade in Johannesburg.) How does this history matter in relation to Muholi’s art?

What does it mean to talk about masculinities rather than “masculinity” in the singular: male masculinities, butch lesbian masculinities, Apartheid masculinities (black and white), stabane masculinities, etc.? How does that shift our understanding of gender and sexuality and assumptions of congruence between them? How can images, such as Muholi’s Miss D’vine, challenge ideas of gender, sexuality, and race, as well as of modernity vs. tradition?

How did Zanele Muholi become a feminist artist? How would you characterize her or her art as feminist? Why does she call herself a visual activist? How might you compare her collaborative art with that of Pushpamala or Navjot?

T 04.28

Amanda Swarr, “Paradoxes of Butchness: Lesbian Masculinities and Sexual Violence in Contemporary South Africa,” Signs

Gabeba Baderoon, “‘Gender within Gender’: Zanele Muholi’s Images of Trans Being and Becoming,” Feminist Studies

Kellie Jones, “Tracey Rose: Post-Apartheid Playground,” Nka: Journal of Contemporary African Art

FILM: Zanele Muholi, Difficult Love screened in class on Th 4.23

For further viewing:

Rape for Who I Am (this film also features Zanele Muholi)

Th 04.30

MIDTERM (first 50 minutes)

Handout: Curatorial Project

Group Work: In-class curatorial project collaboration session

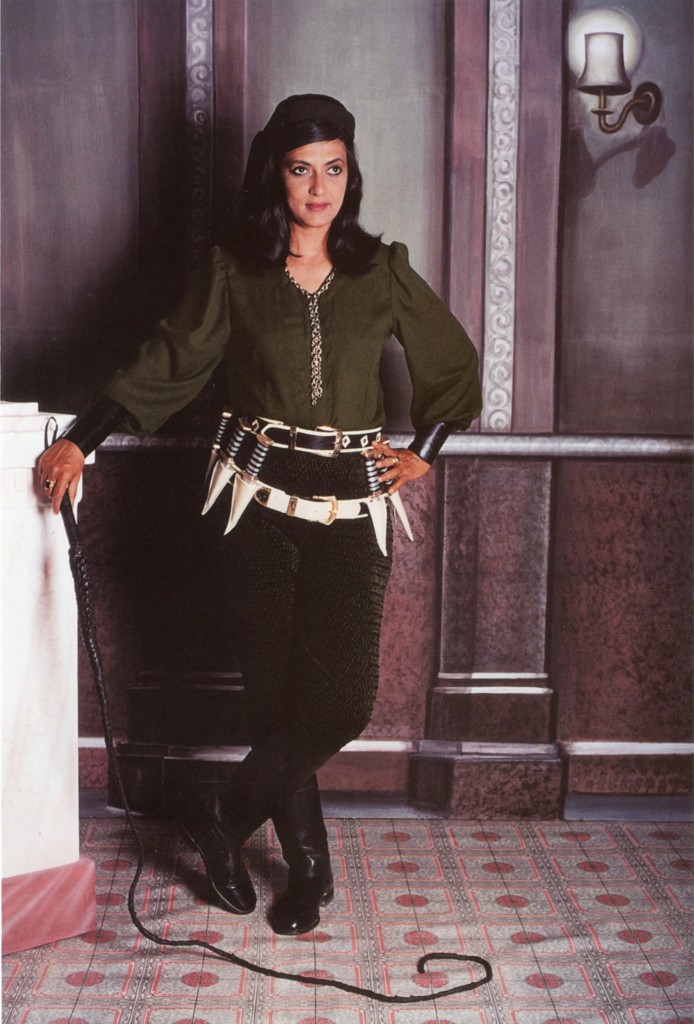

]]>Shirin Neshat

What does Arzoo Osanloo’s chapter help you understand about the history of “women’s rights talk”? What does she mean when she says that it is dialogical? What are the historical and political contingencies in Iran that have shaped women’s rights and their articulation by the women she writes about as an ethnographer? After the 1979 Islamic Revolution, how did the body of Iranian women come to represent the nation, under the Shah and under Khomeini? How is the constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran a hybrid structure? How does it disrupt binaries of Western secular freedom vs. Muslim religious subjugation?

In Iftikhar Dadi’s article “Shirin Neshat’s Photographs as Postcolonial Allegory” about her Women of Allah series, he writes, “The allegorical mode is profoundly ambivalent and complex, and it mediates meaning between realism and fiction in a manner analogous to the effect that the calligraphic screen in Neshat’s photographs creates between the work and the observer.” (128) What are the different kinds of images of veiled women that she alludes to, colonial or anti-colonial? How does she call into question or make more ambivalent and complex their signifying power? What does the calligraphic screen represent, especially for Western viewers who can’t read the script? What does Dadi mean by “postcolonial allegory”?

Why does Neshat set her feature film Women Without Men against the backdrop of the 1953 coup when British and American forces colluded to depose the democratically elected Prime Minister Mohammad Mossadegh? What do you think the four women in the film or the garden where they gather allegorize?

T 05.05

Arzoo Osanloo, The Politics of Women’s Rights in Iran, “A Genealogy of ‘Women’s Rights’ in Iran”

Iftikar Dadi, “Shirin Neshat’s Photographs as Postcolonial Allegory,” Signs

Th 05.07

Film Screening: Shirin Neshat, Women Without Men (This film is based on a novella with the same title by Iranian writer Shahrnush Parsipur.)

Excerpts from Q&A with Neshat as director:

The framing of the story is a fundamental even in Middle Eastern politics–the first and last democratic period in Iran–yet it’s almost unheard of today. Why is August 1953 so unknown outside the Middle East?

I’m not sure why, but I sense it’s only since Sept 11th that the American public has developed a genuine curiosity and interest in Islamic and Middle Eastern cultures and history. As far as I know, in the recent past, very few scholars or the media have pointed back to the Coup of 1953 organized by the CIA, which was directly responsible for the formation of the Islamic Revolution. I happen to believe revisiting history will prove to be helpful so we can put certain facts straight, to comprehend the foundation behind the conflict between the West and Muslims, and to offer new perspectives. For example, how Muslims indeed have been a subject of the criminal behavior of the great Western empires such as the United States and the British.

You’re obviously enchanted by the visual image of the chador. Is this fascination purely cinematic or is there something deeper?

My interest in the veil, or the chador, has both aesthetic and metaphoric reasoning. The veil has always been a complex subject; some consider it an “exotic” emblem, some find it a symbol of “repression,” while others find it a symbol of “liberation.” The veil seems to remain a Western controversy, while in fact the veil s what many Muslim wear in the public domain, so it does not always have to be so politically loaded. In Women Without Men, since it takes place in the 1950s, when the women actually had a “choice” regarding the veil, we have women like Munis and Faezeh, who are constantly veiled, then we have Fakhri who is Westernized and fashionable and not at all covered by it.

The garden figures prominently both in Persian culture and your upbringing. What, for you, is the ultimate significance of the garden, in your culture, your work and in this film?

The concept of a garden has been central to the mystical literature in Persian and Islamic traditions, such as in the classic poetry of Hafez, Khayyam and Rumi where the garden is referred to as the space for “spiritual transcendence.” In Iranian culture, the garden has also been regarded in political terms, suggesting ideas of “exile,” “independence,” and “freedom.” I have made several video-based works in which their concepts explore the symbolic value of the garden in the Islamic tradition. For example, in my brief video installation Tooba, the core of the film was the tree of Tooba, a mythological tree that is regarded as a “a sacred tree,” a “promised tree” in paradise. I created an imaginary garden where the tree of Tooba stood at its center, while a group of people ran toward it to take refuge. Both in Tooba and in Women Without Men the garden is treated as a space of both exile and refuge: an oasis where one can feel safe and secure.

For further exploration:

TED Talk by Shirin Neshat: Art in Exile

Visibility and Visuality: Reframing Gender in the Middle East, North Africa, and Their Diasporas

A special visual issue of Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society

Mona Hatoum

How does Mona Hatoum use installation art to reflect on the politics of displacement, occupation, and diaspora? How does Hatoum engage with intimacy, whether through close-ups such as Corps étranger (1994) or transnationally in such works as Measures of Distance (1988)?

How does her work help you think of relationships between embodiment, performativity, and politics?

How did Mona Hatoum become a feminist artist? How would you characterize her or her art as feminist?

How might you compare Mona Hatoum’s work to that by Shirin Neshat or Anna Mendieta? How does each artist’s work explore loss, intimacy, diaspora, imperialism, sexuality, and bodies?

T 05.12

Rabab Abdulhadi, Evelyn Alsultany, and Nadine Naber, “An Introduction” in Arab & Arab American Feminisms

Salwa Mikdadi Nashashibi, Laura Nader, and Etel Adnan, “Arab Women Artists: Forces of Change,” in Forces of Change

Aruna D’Souza, “Measures of Difference” in Witness to Her Art

Th 05.14

Class Visit: Nadine Naber, Associate Professor, Gender & Women’s Studies, University of Illinois at Chicago

Nadine Naber, “Decolonizing Culture: Beyond Orientalist and Anti-Orientalist Feminisms” in Arab & Arab American Feminisms

Nadine Naber, “Taking Power and Making Power: Resistance, Global Politics, and Institution Building: An Interview with Anan Ameri,” in Arab & Arab American Feminisms

Group Work: In-class curatorial project collaboration session (second 50 min.)

DUE: Wikipedia Gap Analysis

]]>

He Chengyao & Xing Danwen

How have images of “woman” changed throughout modern Chinese history? What is the relationship between visual representations of gendered bodies and political movements such as anti-colonial revolution, socialism, and post-socialist market reform ?

What can you learn about feminism, feminist art, or the politics of exhibit making from the encounter between Judy Chicago and Chinese artists at site six (Lugu Lake) of The Long March: A Walking Visual Display.

What are the body politics of He Chengyao’s performance art pieces? How does she use her own body to question the sociocultural meanings of the female nude? How does she explore through her work the relationship between the personal and the political?

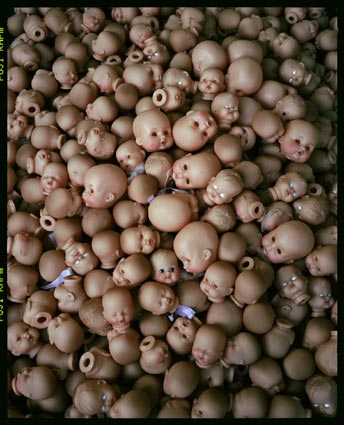

How has Xing Danwen’s photographic practice shifted over time? What do her photographs document? How do the formal choices she makes (about what and how to photograph) convey about labor, environment, gender, and globalization in market-reform China?

T 05.19

Sasha Welland, “What Women Will Have Been: Reassessing Feminist Cultural Production in China,” Signs

Sasha Welland, “The Long March to Lugu Lake: A Dialogue with Judy Chicago,” Yishu

Doris Sung, “Reclaiming the Body: Gender Subjectivities in the Performance Art of He Chengyao,” Negotiating Difference: Contemporary Chinese Art in a Global Context

Th 05.21

Gu Zheng, “Projecting the Reality of China through the Lens: On the Artistic Practice of Xing Danwen,” Yishu

Richard Vine, “Beijing Confidential,” Art in America

]]>Hung Liu & Kim Sooja

What does Shu-mei Shih mean by “feminist transnationality”? How does Hung Liu’s artwork exhibit a kind of feminist transnationality? What are the feminist politics of each identity fragment that Shih proposes? What do you learn about feminism or transnationality through the assemblage of these fragments together? Do you agree that the works Shih interprets can be read along a single vector of antagonism? How does Hung Liu use assemblage within individual artworks?

What does the bottari form (the bundle of old clothes wrapped in a traditional Korean bedcover) in Kimsooja’s work represent? What is the relationship between bottari, textiles, and sewing and her video/performance work in pieces like Needle Woman? How would you compare the body and performance politics of Needle Woman with, for example, those in Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece? How does place, as well as transnational movement, figure in Kimsooja’s work? Does her artwork represent a different kind of feminist transnationality than Hung Liu’s body of work?

T 05.26

Shu-mei Shih, Visuality and Identity, “A Feminist Transnationality”

Joann Moser, “A Conversation with Hung Liu,” American Art

Th 05.28

Daina Augaitis and Kimsooja, “Kim Sooja: Ways of Being” in Kimsooja Unfolding

David Morgan, “Kimsooja and the Art of Place” in Kimsooja Unfolding

Group Work: In-class curatorial project practice and troubleshooting session (second 50 min.)

Handout: Critical Review

For Further Viewing:

Kimsooja, Needle Woman

Kimsooja, Beggar Woman and Homeless Woman

]]>T 06.02

Pecha Kucha Presentations (Groups 1-11)

Th 06.04

Pecha Kucha Presentations (Groups 12-22)

What is PechaKucha?

PechaKucha is the Japanese word for conversation or “chit chat.” Created by two architects in Tokyo who were tired of dreadful PowerPoint presentations, PechaKucha is designed to force speakers to prepare shorter, more creative, and more polished presentations. More importantly, designing a PechaKucha presentation motivates speakers to think about their subjects in very different ways.

What are the characteristics of PechaKucha?

- A presentation is created using PowerPoint (or any other presentation software).

- Presenters are only allowed 20 slides and those slides must automatically advance every 20 seconds (thus the “20 x 20” label).

- Consequently, presentations should never be longer than 6 minutes 40 seconds.

- Because of this format, the PowerPoint slideshow must depend on visuals, rather than

text-heavy slides. This is one of the best characteristics since speakers often abuse

text in slideshows. - Presentations are expected to have structure, including an introduction and conclusion

and an internal structure (clear main points, transitions) that will guide the audience through the slide show. In other words, the words and the visuals should complement each other rather than just mirroring each other. - Presentations are expected to be polished and engaging. Because of the time constraints, the auto-advancing slides, and the format, speakers should spend more time planning and practicing their presentations.

- Audiences are more likely to be engaged. It’s sad, but true—we don’t have a very long attention span. Consequently, speakers need experience presenting their ideas in a short period of time and in a more creative, engaging way.

PechaKucha website

This is the official PechaKucha website, where you can watch sample presentations.

PechaKucha presentation on Feminist Asian American artist Su-En Wong

This example from the PechaKucha website will give you a good sense of a presentation on a topic related to the course. Keep in mind, however, that your presentation should not be about a single artist (or set of artists) but about your exhibit proposal.

A PechaKucha about PechaKucha

This presentation gives a good overview of the format and how to prepare a presentation (forgive his humor with slides like “Dude’s Law). Especially useful are his tips on staying away from your computer in the development stage and using index cards to storyboard your ideas and develop a thoughtful narrative flow.

PechaKucha on creating and presenting a PechaKucha

Matthew Bird, an instructor at the Rhode Island School of Design, gives pointers based on what he’s learned from having students in his History of Industrial Design class present using the PechaKucha format.

How to create a PechaKucha using PowerPoint

This YouTube how-to video is boring and technical, but in three minutes it will walk you through the basics of how to create twenty slides in PowerPoint and set up the twenty second timing.