The tissues of the skeletal system, bone and cartilage, are

specialized types of connective tissue. Unlike epithelia,

connective tissue consists of scattered cells and an abundance of

extracellular material. Connective tissue cells synthesize

and secrete proteins such as collagen that assemble into large

fibers to give structure to the tissue. Bone tissue is rigid

and strong because mineral salts of calcium are deposited within

the framework of collagen fibers. Cartilage is solid and

flexible tissue containing a large amount of proteoglycans

(sugar-linked proteins) among the collagen fibers of the

extracellular matrix. The proteoglycans contribute to the

physical properties of cartilage that allow it to resist

compression.

At the gross level, it is possible to distinguish two basic types

of bone tissue: compact bone

and trabecular

bone (trabecular bone is also called

spongy bone or cancellous bone). Compact bone is dense and

solid, while trabecular bone consists of a fine network of

interlocking struts. Compact bone forms the outer layer of

long bones, while trabecular bone is found in the central cavity,

and also at the ends of bones. The figure below shows a

tibia that has been sectioned longitudinally, so that you can

compare compact bone to trabecular bone.

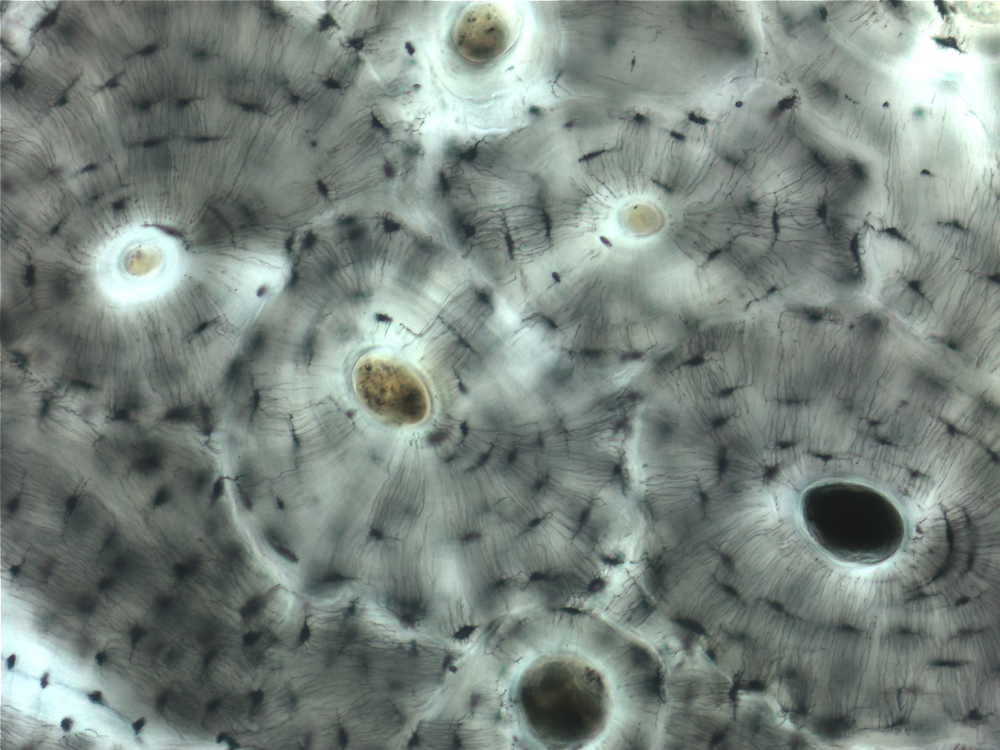

There are three basic types of cells found in bone: osteoblasts, osteocytes, and osteoclasts (see page about bone remodeling). The slides below are of thin ground sections of dried bone, and so the living cells are not visible. However, this type of preparation is good for revealing the spaces and fine channels that are occupied by osteocytes (bone cells) in the living bone.

This picture shows

compact bone at low magnification. Compact bone consists of

many parallel units called osteons

that are tightly packed together to form the strong outer layer of

bone. The large circles that you see at the centers of the

osteons are channels known as Haversian

canals. In the living tissue, the Haversian

canals are occupied by blood vessels and nerves. Each osteon

consists of concentric layers of bone tissue surrounding a

Haversian canal. For a schematic view showing the

organization of bone tissue, look at Figure 10.10 in Wheater's

Functional Histology (see lecture slides).

This picture shows

compact bone at low magnification. Compact bone consists of

many parallel units called osteons

that are tightly packed together to form the strong outer layer of

bone. The large circles that you see at the centers of the

osteons are channels known as Haversian

canals. In the living tissue, the Haversian

canals are occupied by blood vessels and nerves. Each osteon

consists of concentric layers of bone tissue surrounding a

Haversian canal. For a schematic view showing the

organization of bone tissue, look at Figure 10.10 in Wheater's

Functional Histology (see lecture slides).

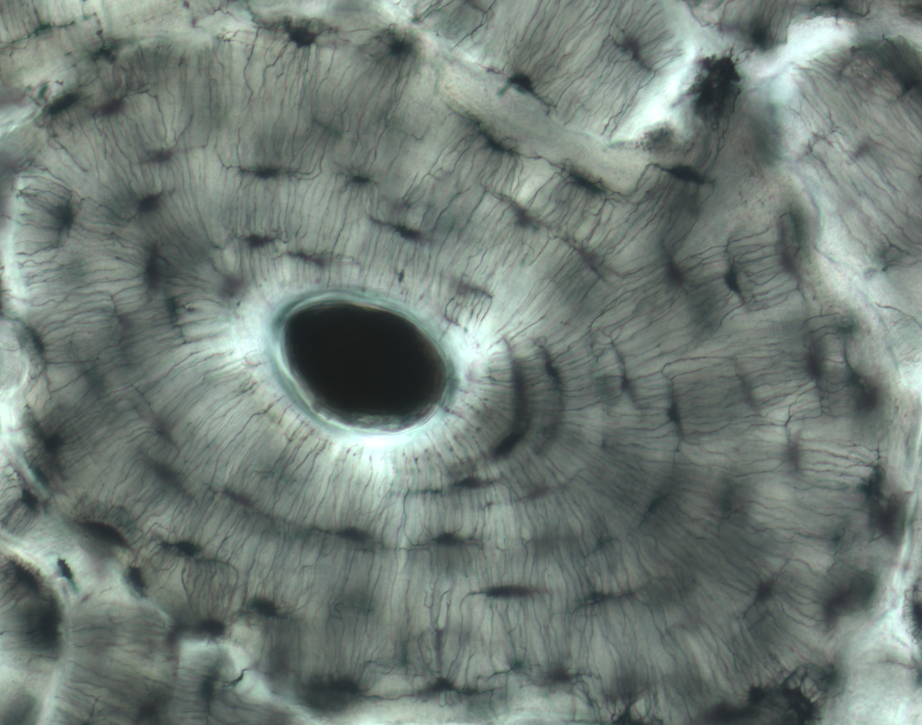

In the higher

magnification view at right, you can see that there are black

spaces arrayed around the central Haversian canal. These

spaces are called lacunae

(singular: lacuna)

and contain osteocytes in

living bone. Because osteocytes are enclosed within layers of

bone, they need to have a way to receive nutrients and communicate

with other cells. So each osteocyte extends fine cellular

processes through narrow channels called canaliculi

(singular: canaliculus).

In the slide at right, the canaliculi are the fine black lines

extending perpendicularly from each lacuna.

In the higher

magnification view at right, you can see that there are black

spaces arrayed around the central Haversian canal. These

spaces are called lacunae

(singular: lacuna)

and contain osteocytes in

living bone. Because osteocytes are enclosed within layers of

bone, they need to have a way to receive nutrients and communicate

with other cells. So each osteocyte extends fine cellular

processes through narrow channels called canaliculi

(singular: canaliculus).

In the slide at right, the canaliculi are the fine black lines

extending perpendicularly from each lacuna.

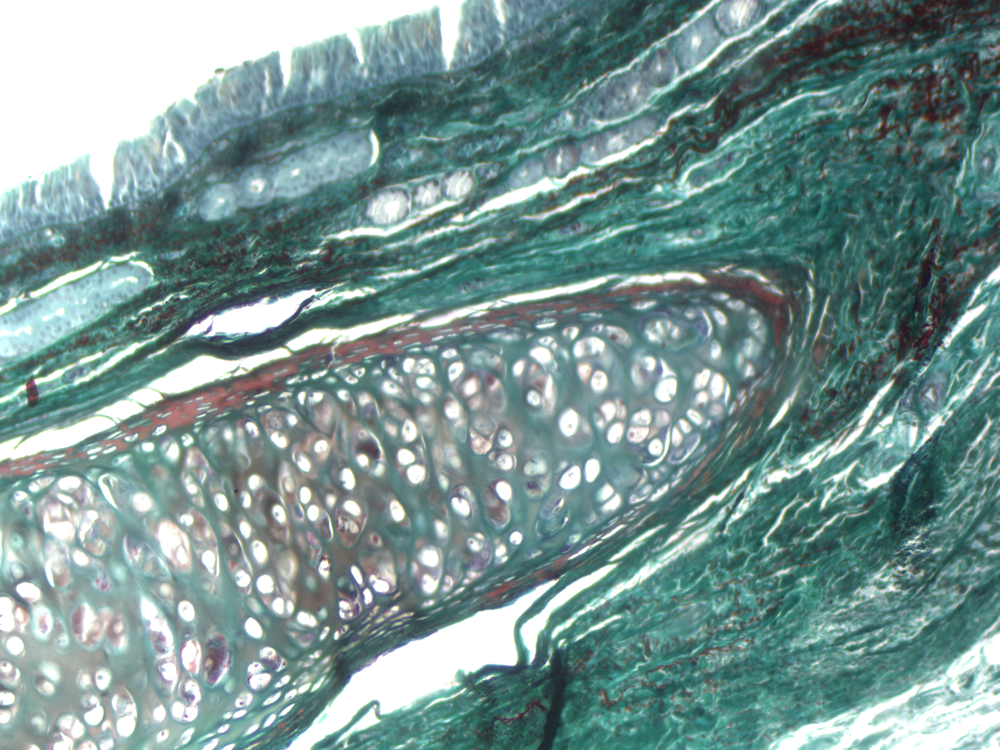

Cartilage is found in a layer at the ends of bones where they form joints (the articular cartilage; we will look at joints next week). Cartilage also forms structural rings and plates in the large airways of the respiratory tract. The slides below are sections from the trachea.

The trachea is the large

central airway that connects the upper respiratory tract (nasal

passages, oral cavity, throat structures) to the airways that lead

to the lungs. The trachea is held open by rings of cartilage.

These rings do not form a complete circle; instead they have the

shape of a C. The picture at right shows the end of one of the

C-shaped rings of cartilage extending off to the lower left.

The trachea is the large

central airway that connects the upper respiratory tract (nasal

passages, oral cavity, throat structures) to the airways that lead

to the lungs. The trachea is held open by rings of cartilage.

These rings do not form a complete circle; instead they have the

shape of a C. The picture at right shows the end of one of the

C-shaped rings of cartilage extending off to the lower left.

The specific type of cartilage found in the trachea and in the

articular cartilage is called hyaline

cartilage. Hyaline means glassy, and this

type of cartilage has a smooth and translucent appearance.

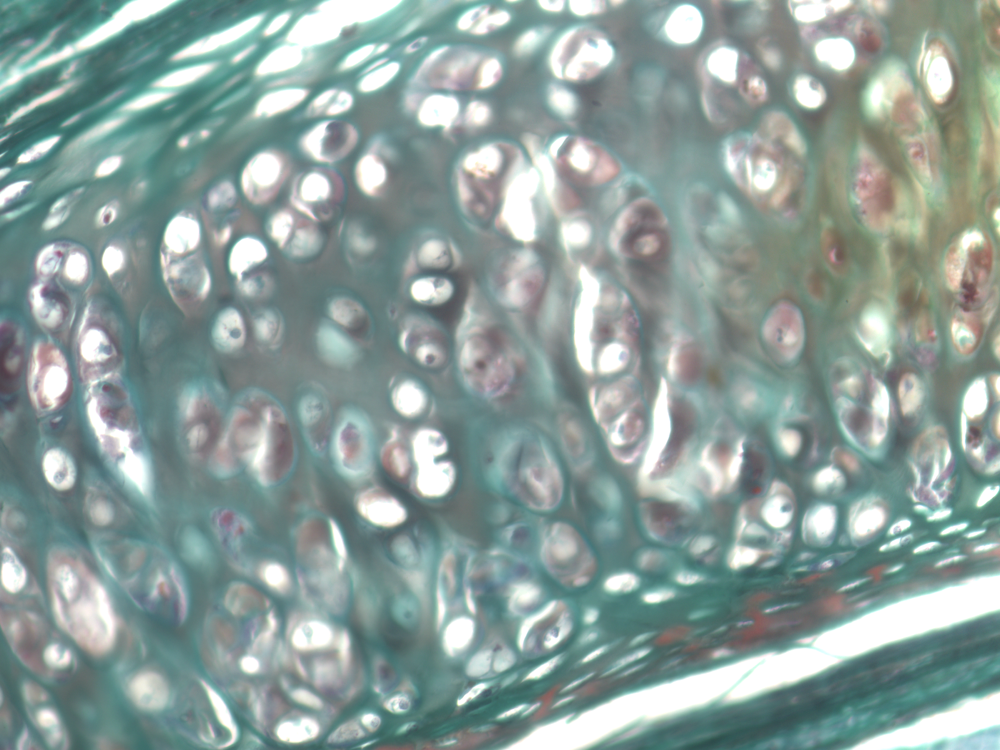

At the microscopic level,

cartilage has the appearance of Swiss cheese. In the living

tissue, each space that you see is occupied by a cartilage cell,

called a chondrocyte. As in

bone tissue, the spaces are called lacunae

(singular: lacuna).

Unlike bone, cartilage is not penetrated by blood vessels. This

limits how thick cartilage can become since nutrients must diffuse

through the tissue to reach cells. Cartilage also has much less

capacity for repair. Damage to articular cartilage is what

occurs in arthritis.

At the microscopic level,

cartilage has the appearance of Swiss cheese. In the living

tissue, each space that you see is occupied by a cartilage cell,

called a chondrocyte. As in

bone tissue, the spaces are called lacunae

(singular: lacuna).

Unlike bone, cartilage is not penetrated by blood vessels. This

limits how thick cartilage can become since nutrients must diffuse

through the tissue to reach cells. Cartilage also has much less

capacity for repair. Damage to articular cartilage is what

occurs in arthritis.