Epithelial Histology

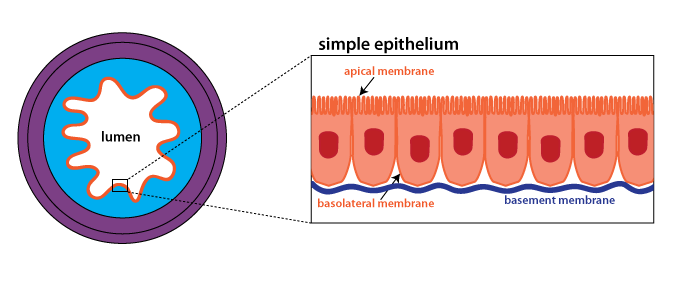

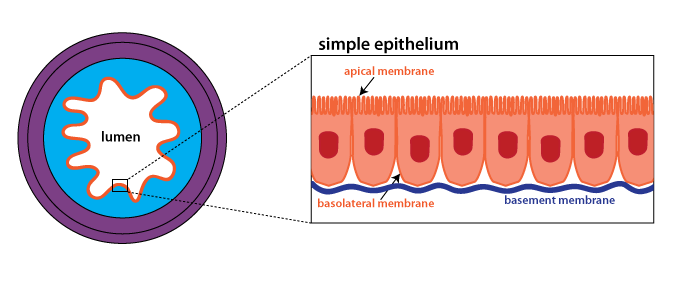

An epithelium is the type of tissue that covers surfaces,

usually the linings of hollow organs in the body, or in the case

of the skin, the outer surface of the body. In many cases,

adjacent epithelial cells are linked by tight

junctions so that the epithelium forms a barrier

that regulates the movement or substances across it (see the web

page on Epithelial

Transport). The figure below shows a schematic of a

simple epithelium, modeled after the epithelium lining the small

intestine.

Epithelia are comprised almost entirely of cells. The apical surface faces the lumen (inside of a hollow organ)

while the basal or basolateral surface is adjacent to

the underlying tissue. In many epithelia, the apical surface

is specialized. For instance, in the small intestine, the

apical plasma membrane is folded into microvilli

(see below) to increase the surface area for absorption of

nutrients. Every epithelium has a basement

membrane, that binds the epithelium to the

underlying connective tissue. The basement membrane consists

of a thin layer of extracellular proteins that is located next to

the basolateral surface. Blood vessels do not penetrate

through the basement membrane. In practice, the basement

membrane is too small to be seen except on an electron micrograph

(EM). In the lecture we will look at an EM of the skin

epithelium that shows the basement membrane.

Epithelia are classified according to whether they consist of a

single layer of cells (simple) or multiple layers of cells

(stratified). Epithelia are also classified by the shape of

the cells: squamous (flat), cuboidal, or columnar.

Be able to identify the following examples, where they are found

in the body, and what type of epithelium they are

(for example: simple squamous epithelium). Terms shown

in purple boldface may appear

on a quiz section test.

In the textbook*, figure 3.10 (p. 78) is a useful overview of

different types of epithelia. In this figure, epithelia are

classified according to function, as opposed to shape and cell

number. Figure 3.15 (p. 86) illustrates the structure of the skin.

*Pages and figure numbers refer to the 8th

edition of Human Physiology: An Integrated Approach by

Dee Silverthorn.

Examples

Epidermis of the Skin

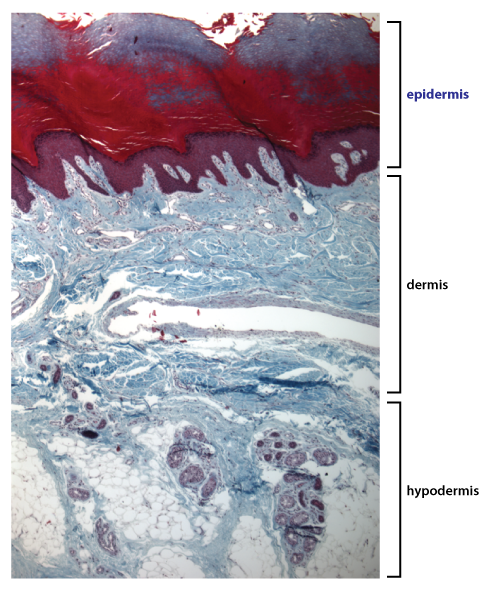

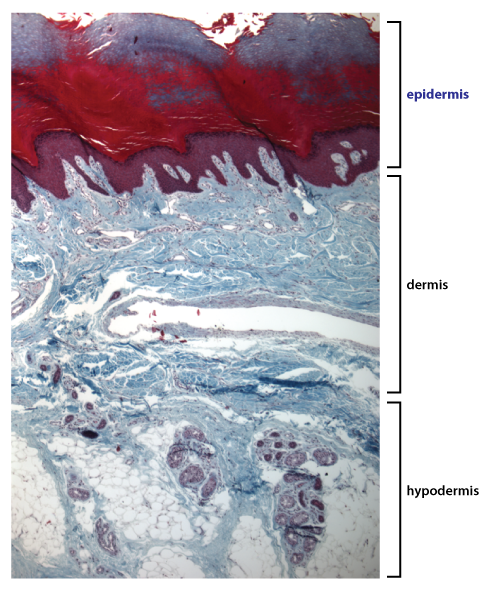

The figure at right shows a low-magnification view of thick skin,

such as you would find on the surface of your fingertip where your

fingerprint is. At this low magnification you can see the

three layers in the skin. The outer region is the epidermis, which forms the surface

of the skin. The middle region is the dermis, which contains

dense connective tissue, blood vessels, and nerves. The

innermost layer is the hypodermis, which contains loose connective

tissue and adipose tissue, along with sweat glands, blood vessels,

and nerves.

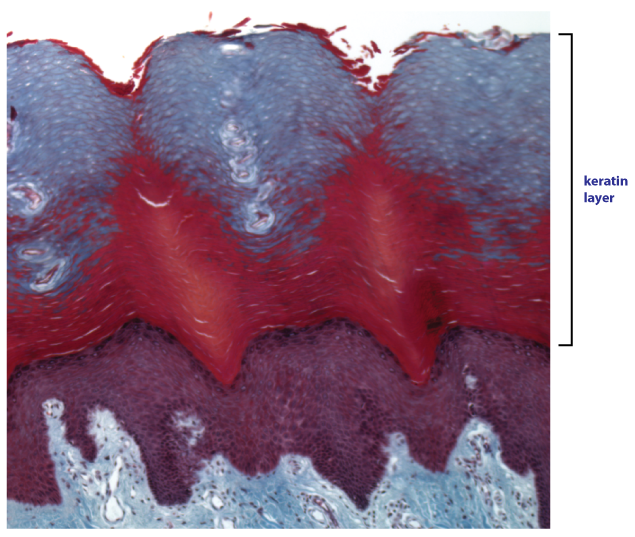

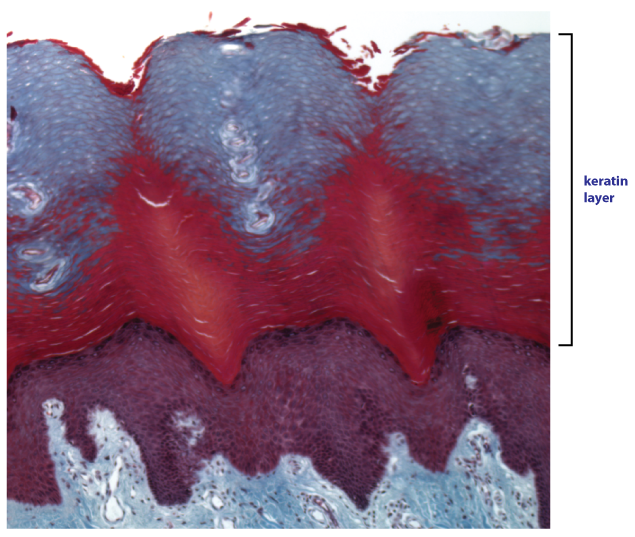

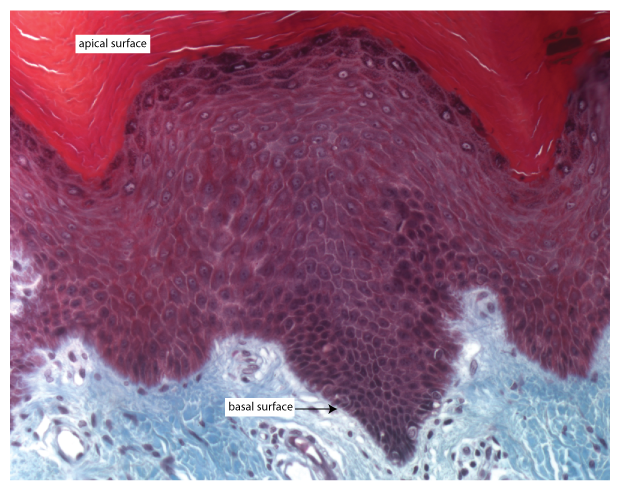

This next image is at higher magnifcation and focuses in on the

epidermis. The epidermis is classified as a stratified

squamous keratinized epithelium. Cells divide

at the basal surface of the epithelium, and as new cells are

generated, older cells are pushed towards the apical

surface. As cells move apically, they become very flattened

(squamous) and they fill up with an intracellular protein called keratin (for this reason, cells in

the epidermis are referred to as keratinocytes).

This

type

of epithelium is protective, with the keratin

layer acting to protect the underlying tissue from

abrasion and dehydration.

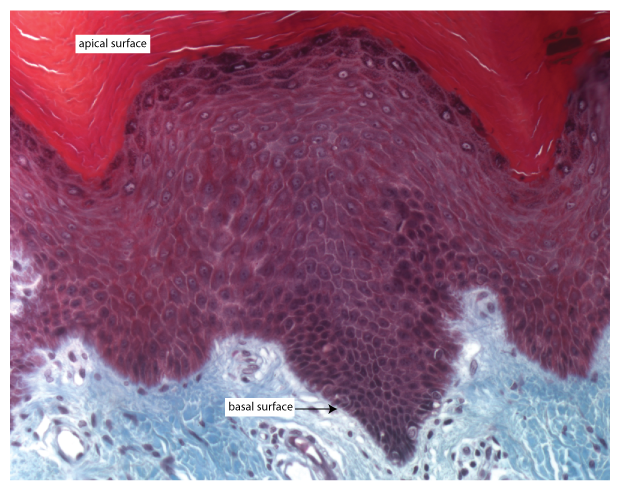

This image focuses on the keratinocytes

(purple layer) at high magnification. Note that cells appear

dark at the apical surface, where they are filling up with

keratin.

OPTIONAL: Melanocytes, which produce pigment, are

located on the basal surface of the epidermis. Although they

produce pigment, their cytoplasm appears clear in this stain. See

if you can find a melanocyte in this picture.

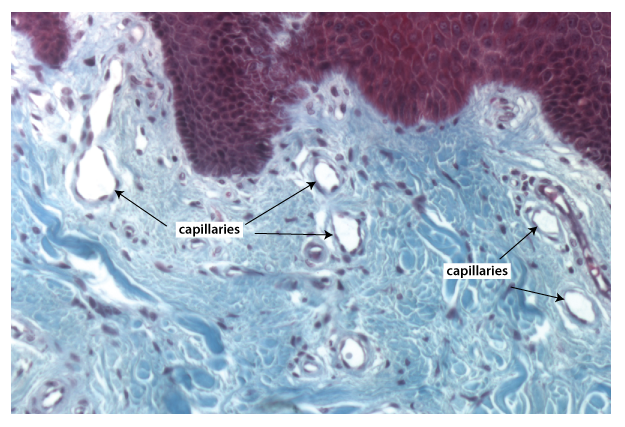

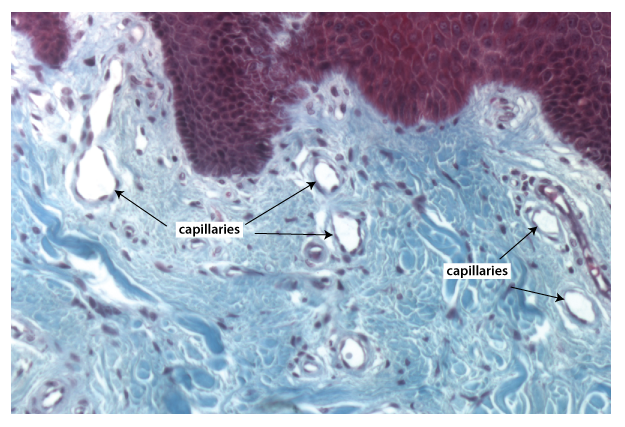

Endothelium

The endothelium is the simple squamous epithelium that

lines all blood vessels. The very smallest vessels,

capillaries, are made up of just endothelium. A healthy and

intact endothelium acts as a barrier that isolates the blood from

underlying tissue, preventing the formation of a blood

clots. Endothelial cells also send important signals,

affecting things such as tissue growth and blood flow. In

the brain, there are tight junctions

between endothelial cells, limiting the permeability of the

endothelium, and protecting neurons in the brain from toxins and

other potentially neuroactive substances in the blood. This

functional barrier is known as the blood-brain

barrier.

The image below shows capillaries in the upper part of the

dermis. Note how each white space is outlined by a single

layer of thin dark cells; this is the endothelium.

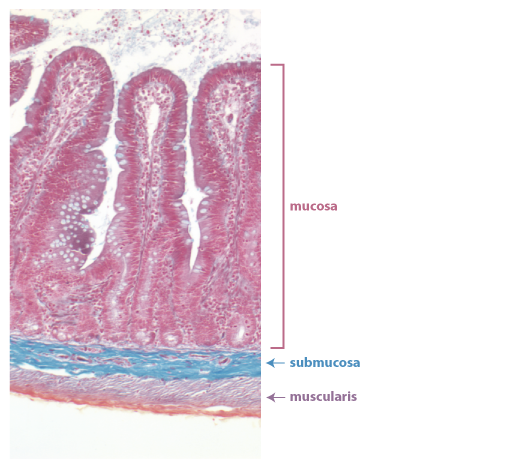

Small Intestine

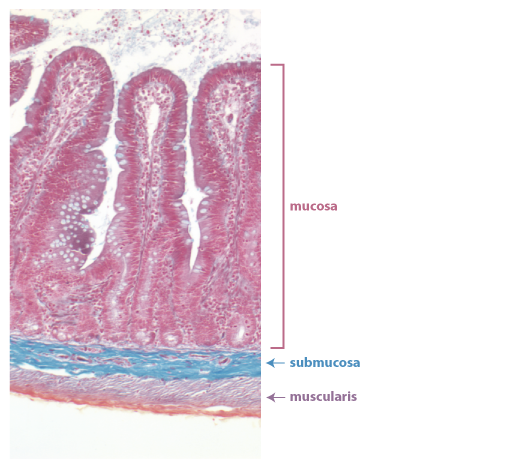

This low-magnification view shows the different

regions of the small intestine. In the digestive tract and

other organs, the layer of tissue next to the lumen is called the

mucosa. The mucosa is sometimes called a "mucous

membrane" because it is covered with a layer of mucus. The

mucosa consists of a small amount of connective tissue and a

highly folded simple columnar epithelium.

The folds of tissue that poke out are called villi

(singlular: villus), and the folds that dip down are called

crypts. The folding of the epithelium increases the surface

area available for absorption of nutrients.

This low-magnification view shows the different

regions of the small intestine. In the digestive tract and

other organs, the layer of tissue next to the lumen is called the

mucosa. The mucosa is sometimes called a "mucous

membrane" because it is covered with a layer of mucus. The

mucosa consists of a small amount of connective tissue and a

highly folded simple columnar epithelium.

The folds of tissue that poke out are called villi

(singlular: villus), and the folds that dip down are called

crypts. The folding of the epithelium increases the surface

area available for absorption of nutrients.

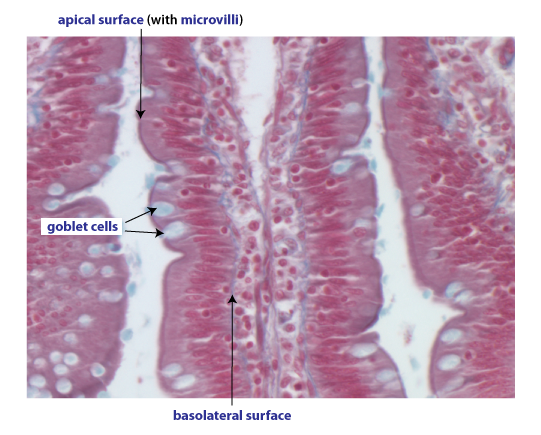

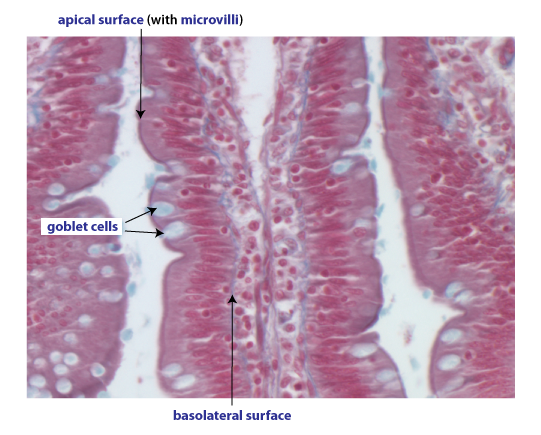

The image at the left shows part of a villus at high

magnification. The absorptive cells (pinkish red) in the simple columnar epithelium are

called enterocytes.

Scattered among the enterocytes are mucus-secreting cells called goblet cells that stain pale

blue. At the apical surface of the enterocytes, there is a

dark line which occurs due to a web of proteins that anchor the microvilli, folds of the apical

plasma membrane that further increase the surface area for

absorption. Another term for the microvilli is "brush

border". We will look at several EMs that show microvilli in

the lecture.

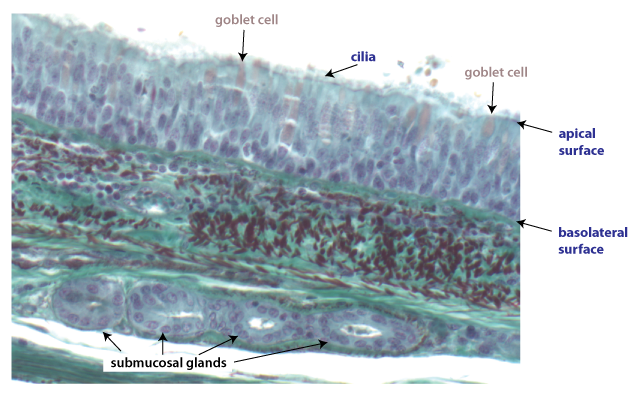

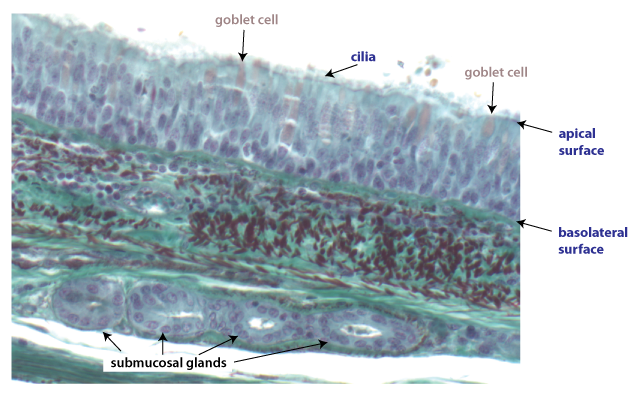

Airway Epithelium

The airway epithelium

lines the passages that conduct air into the lungs. (Airways

conduct air into the lungs whereas tiny sacs called alveoli are

where gas exchange occurs.) The airway epithelium is

classified as a pseudostratified

ciliated epithelium. Although it is a simple

epithelium, it appears stratified because nuclei of different

cells are at different heights, hence the term

"pseudostratified". An important function of this epithelium

is the movement of mucus out of the respiratory tract.

Mucus, which is secreted by goblet cells and submucosal glands,

traps particles and pathogens. The beating of the cilia, located at the apical surface, moves the mucus

toward the pharynx (throat) where it can be swallowed.

The airway epithelium

lines the passages that conduct air into the lungs. (Airways

conduct air into the lungs whereas tiny sacs called alveoli are

where gas exchange occurs.) The airway epithelium is

classified as a pseudostratified

ciliated epithelium. Although it is a simple

epithelium, it appears stratified because nuclei of different

cells are at different heights, hence the term

"pseudostratified". An important function of this epithelium

is the movement of mucus out of the respiratory tract.

Mucus, which is secreted by goblet cells and submucosal glands,

traps particles and pathogens. The beating of the cilia, located at the apical surface, moves the mucus

toward the pharynx (throat) where it can be swallowed.

This low-magnification view shows the different

regions of the small intestine. In the digestive tract and

other organs, the layer of tissue next to the lumen is called the

mucosa. The mucosa is sometimes called a "mucous

membrane" because it is covered with a layer of mucus. The

mucosa consists of a small amount of connective tissue and a

highly folded simple columnar epithelium.

The folds of tissue that poke out are called villi

(singlular: villus), and the folds that dip down are called

crypts. The folding of the epithelium increases the surface

area available for absorption of nutrients.

This low-magnification view shows the different

regions of the small intestine. In the digestive tract and

other organs, the layer of tissue next to the lumen is called the

mucosa. The mucosa is sometimes called a "mucous

membrane" because it is covered with a layer of mucus. The

mucosa consists of a small amount of connective tissue and a

highly folded simple columnar epithelium.

The folds of tissue that poke out are called villi

(singlular: villus), and the folds that dip down are called

crypts. The folding of the epithelium increases the surface

area available for absorption of nutrients.

The airway epithelium

lines the passages that conduct air into the lungs. (Airways

conduct air into the lungs whereas tiny sacs called alveoli are

where gas exchange occurs.) The airway epithelium is

classified as a pseudostratified

ciliated epithelium. Although it is a simple

epithelium, it appears stratified because nuclei of different

cells are at different heights, hence the term

"pseudostratified". An important function of this epithelium

is the movement of mucus out of the respiratory tract.

Mucus, which is secreted by goblet cells and submucosal glands,

traps particles and pathogens. The beating of the cilia, located at the apical surface, moves the mucus

toward the pharynx (throat) where it can be swallowed.

The airway epithelium

lines the passages that conduct air into the lungs. (Airways

conduct air into the lungs whereas tiny sacs called alveoli are

where gas exchange occurs.) The airway epithelium is

classified as a pseudostratified

ciliated epithelium. Although it is a simple

epithelium, it appears stratified because nuclei of different

cells are at different heights, hence the term

"pseudostratified". An important function of this epithelium

is the movement of mucus out of the respiratory tract.

Mucus, which is secreted by goblet cells and submucosal glands,

traps particles and pathogens. The beating of the cilia, located at the apical surface, moves the mucus

toward the pharynx (throat) where it can be swallowed.