World Heritage:

Conservation Efforts in the

By Jeanine Riss

Abstract

The United

Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) strive to

advance the fields of human and social science, natural science and culture. Under the theme of culture they have created

the World Heritage List which encompasses those properties which exhibit unique

cultural or natural merit and possess a common heritage for humanity. As members of the World Heritage Convention,

the

Introduction

The preservation of our natural and

cultural heritage for present and future generations is an obligation dutifully

accepted by the many conscientious nations who consider their national treasures

to be of momentous value, not only to themselves, but to humanity. No where more so is this obligation to

conserve the natural and human wrought wonders within their boundaries felt

than in the

UNESCO and World Heritage

UNESCO’s

foundations were laid in the last years of the Second World War. Several European countries came together in

1942 in the

|

|

|

The opening of UNESCO's first General Conference at the

Sorbonne, Paris (20 November to |

|

© UNESCO/Eclair Mondial |

Figure 1. Courtesy of UNESCO.

UNESCO’s mission is many fold. It is fundamental in the advancement of education, the natural sciences, the human and social sciences, communication, information and culture. Under the theme of culture is found the subject of World Heritage. World Heritage is the preservation of both cultural and natural places that embody universal merit for all humanity. To be a designated a World Heritage Site is to be part of 812 unique localities that are deemed to be of significant importance to humanity, both present and future. World Heritage Sites are divided into three categories: natural, cultural and a combination of both natural and cultural or mixed properties. Currently there are 160 natural, 628 cultural and 24 mixed World Heritage Sites (Figure 2).

Figure 2. World Heritage map courtesy of

UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

Once an area of interest is accepted to the World Heritage list and the country of origin ratifies the World Heritage Convention, it receives the protection and assistance of UNESCO (UNESCO World Heritage Centre 2006).

UNESCO adopted the Convention Concerning the Protection of the World Cultural and Natural Heritage in 1972 (UNESCO World Heritage Centre 2006). The World Heritage Convention recognizes the intrinsic link between humanity and nature and the necessity to conserve the natural world in order to advance the benefits we receive through our connection with nature and to preserve the natural world in its own right. It also recognizes the significance of our diverse cultural heritage. Diversity of culture enhances individuals and when brought together strengthens humanity as a whole. To preserve sites of cultural importance provides a sense of continuity and unity of purpose as well as a connection to history for the people of that culture, at the same time allowing the world to partake of the richness of human endeavors from ages past.

The

World Heritage Convention emerged from the union of two distinct movements,

those of nature conservation and preservation of culturally important locations. A momentous event took place in 1959 that

brought together these two ideals. A

proposal was put forth in that year to build the Aswan High Dam in

UNESCO’s goal in regards to the preservation of our cultural and natural heritage is comprehensive. It advocates participation of all nations in the World Heritage Convention in order to safeguard our natural and cultural heritage. It seeks to inspire States Parties (those countries that adhere to the World Heritage Convention) to nominate potential sites within their national boundaries. UNESCO will provide training and technical assistance to better protect vulnerable sites and will work with States Parties to promote management plans for the conservation of World Heritage properties. UNESCO will also supply emergency aid for those sites in imminent danger. It seeks to raise public awareness in issues of conservation and to engage the indigenous population in the management of their own unique heritage (UNESCO World Heritage Centre 2006).

For a property to be considered for inclusion onto the World Heritage List a nation must first have signed the World Heritage Convention and by doing so commit to preserving their natural and cultural heritage. The First step in the nomination process is for the country to make an inventory or “Tentative List” of the significant cultural or natural locations within their borders. These sites may be submitted for inscription within five to ten years. Second, the States Party submits a nomination file with appropriate documentation and maps for those sites on the Tentative List. After receiving the nomination file the World Heritage Centre submits it for evaluation to the appropriate Advisory Bodies (UNESCO World Heritage Centre 2006).

The

International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) evaluates prospective

cultural properties (Khatwa 2006).

ICOMOS was founded in

Once a year the World Heritage Committee decides which sites will be afforded World Heritage status. A submitted property must meet one of ten selection criteria to become a World Heritage Site. They are as follows:

i.

“to represent a masterpiece of

human creative genius;

ii.

to exhibit an important

interchange of human values, over a span of time or within a cultural area of

the world, on developments in architecture or technology, monumental arts,

town-planning or landscape design;

iii.

to bear a unique or at least

exceptional testimony to a cultural tradition or to a civilization which is

living or which has disappeared;

iv.

to be an outstanding example of

a type of building, architectural or technological ensemble or landscape which

illustrates (a) significant stage(s) in human history;

v.

to be an outstanding example of

a traditional human settlement, land-use, or sea-use which is representative of

a culture (or cultures), or human interaction with the environment especially

when it has become vulnerable under the impact of irreversible change;

vi.

to be directly or tangibly

associated with events or living traditions, with ideas, or with beliefs, with

artistic and literary works of outstanding universal significance. (The

Committee considers that this criterion should preferably be used in

conjunction with other criteria);

vii.

to contain superlative natural

phenomena or areas of exceptional natural beauty and aesthetic importance;

viii.

to be outstanding examples

representing major stages of earth's history, including the record of life,

significant on-going geological processes in the development of landforms, or

significant geomorphic or physiographic features;

ix.

to be outstanding examples

representing significant on-going ecological and biological processes in the

evolution and development of terrestrial, fresh water, coastal and marine

ecosystems and communities of plants and animals;

x.

to contain the most important

and significant natural habitats for in-situ conservation of biological

diversity, including those containing threatened species of outstanding

universal value from the point of view of science or conservation” (UNESCO

World Heritage Centre 2006).

There is another aspect to being part of the World Heritage List. When an

existing inscribed property is in danger of losing those qualities which made it worthy of World Heritage status it may be placed on the List of World Heritage in Danger. Whether through natural disaster, war, urbanization, tourism or pollution sites may be in imminent or potential danger of losing those characteristics for which they were prized. By being placed on the List of World Heritage in Danger this allows the World Heritage Fund to offer immediate assistance and to garner attention from the international community in order to preserve the endangered site in a timely and efficient manner. In conjunction with the State Party of the property concerned, the World Heritage Committee can develop a plan of corrective action in order to preserve the site. If the problems for which a site was placed on the List in Danger go uncorrected, the World Heritage Committee may elect to remove it from the World Heritage List. To date this option has not been applied (UNESCO World Heritage Centre 2006).

World Heritage in

Although the

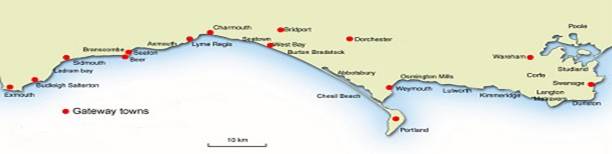

Figure 3. Map of

The

primary significance as a World Heritage Site comes from the area’s almost

continuous geologic formations documenting the Mesozoic Era or approximately

185 million years of our planet’s history.

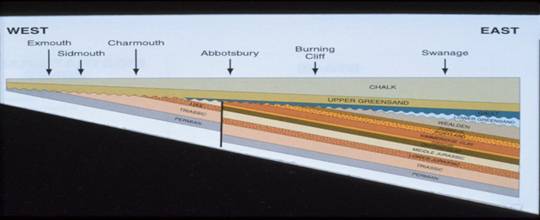

The strata exposed along this section of

Figure 4. Example of geologic conditions of the

The exposure by continued erosion and easy access to outcroppings in such sequential order has made the Jurassic Coast of paramount importance to the study of earth sciences for the past 300 years (Jurassic Coast 2006). There are 6 specific aspects endemic to the site that justifies its World Heritage status. Its unique geology showcases 185 millions years of Earth history. A tremendous wealth of fossils (Figure 5) documenting a wide range of species provides “evidence of major changes in the pattern of life on Earth” (Jurassic Coast 2006). The exceptional examples of geomorphologic features and processes (Figure 6) provides numerous opportunities for study and ongoing research and the area as a whole as been of supreme importance in establishing the era of modern geology.

Figure 5. Ammonite fossil. Figure 6. Lulworth Crumple/Stair Hole

Lulworth Cove,

Courtesy of JurassicCoast.com

It is also an area of extreme aesthetic beauty (Figure 7) with a natural undeveloped coastline and

rural countryside (Jurassic Coast 2006).

Figure 7. Near Durdle

Door,

In

the category of cultural sites the

Figure 8-9.

Romans Bathes and Mosaic Tiles.

First founded by

the Anglo-Saxon around 757 A.D., Bath Abbey has seen several restorations. A Norman cathedral was begun in 1090. The present church was started in 1499, but

suffered ruin under Henry IIIV in 1539 during the dissolution. Major restoration was begun in the 1860s, but

the Abbey again suffered damage when

Figure 10-11.

Other

attributes establishing

Figure 11. Skellig Michael, courtesy of UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

The Archeological

Ensemble of the

Figure 12. Megalithic art from passage tomb.

Courtesy of UNESCO World Heritage Centre.

There

are several sites, both natural and cultural, on

Figures 13-14. Rock of

Figure 15.

Other Conservation Efforts

Other designations

for areas of conservation exist beside that of World Heritage Sites. Sites of Special Scientific Interest or SSSI

sites are assigned for the preservation of natural heritage. In

Figures 16-17. Charmouth beach,

Another

designation is Areas of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB). These sites are chosen for their landscape

qualities with the purpose of preserving their natural beauty. Featured characteristics of conservation

importance include flora, fauna, geological and landscape features and the

history of human colonization of the area.

The National Parks and Access to the Countryside Act of 1949 laid the

foundations for protecting particularly beautiful and diverse countryside by

designating it as an AONB. The agency

responsible for designating AONBs is The Countryside Agency. There are 36 AONB sites in

Conclusion

Whether

it is the history of a planet engraved in stone or the majestic beauty of wave-

swept cliffs, the grandeur and elegance of a cathedral raised on high or the

mysterious allure of a centuries old passage tomb our cultural and natural

heritage is a legacy worthy of our utmost care and attention. As citizens of the world we have a

responsibility to ensure the conservation and to provide assistance for the

protection of the natural world as well as those wonders wrought by human

invention. Organizations such as UNESCO

and the designation of World Heritage Sites are of paramount importance in the maintaining

those areas of unique quality and universal merit. The

Works Cited

Bath & North

Black, Katie.

2006.

City of

English Nature. 2006.

Henderson, S.

Lecture. TESC 332. Issues in Conservation Biology.

ICCROM: International Centre for the Study of the

Preservation and Restoration of Cultural Property. 2005.

ICOMOS. 2005.

ICOMOS. 2005.

ICOMOS. 2005.

Khatwa, Dr. Anjana.

2006.

The Countryside Agency.

2006.

UNESCO. 2006.

UNESCO World Heritage Centre. 2006.

World Conservation

World Heritage Site.

2006.

Back to Student Project