Building England’s Castles:

A Look at

Some of the Chosen Locations, Building Materials, and a Peek into Their History

TESC 417

Kathy

Deraitus

August, 2006

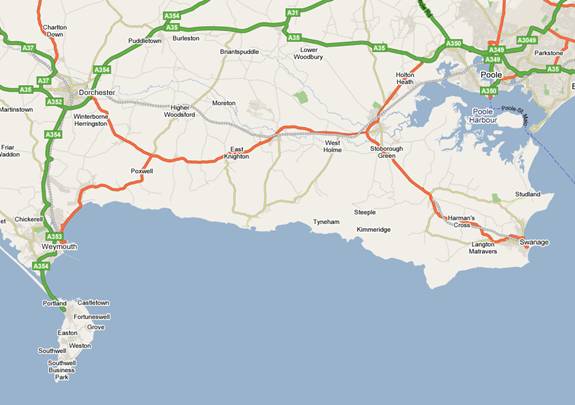

Location of Corfe, Lulworth and Portland Castles

Map by Google.com

During my travels with the University of Washington geology class in July/ August, 2006, I had the

opportunity to visit a variety of castles along the South West Coast of England and within the interior. It’s one thing to see pictures in a book or

watch a movie on castles, but the chance to actually walk into one of these

majestic buildings is an awe-inspiring experience—it was truly a walk back in

time. Why these stone castles were built

in their chosen locations, and the materials the people used to build

them, and why they designed them in the

manner they did, gives us an opportunity to understand English life dating back

to the time of the Normans and Saxons—and gives us insight into a very exciting

time in England’s history. Let’s take a

step back in time.

Military defenses, in one form or another, have

populated English lands as far back in history as 1000 BC. These defenses, although much more primitive

than the spectacular stone forms of castles we know today, nonetheless served

as a form of protection for the community.

These precursors to the English castles would range anywhere from a type

of hillfort of loops, ditches and banks used during the Bronze Age to the early

timber castles built by the Normans. Going

forward in time, these fortifications evolved into the majestic and awe-inspiring

stone castles that we see today. Castles

were built for a variety of reasons and uses. They might serve as a stronghold

to protect the peoples of the town from invasion—from the royal kings and

queens, to the wealthy lords and ladies, and to poorest of the peasants. They were a show of strength and power for

land-owning lords and a mighty symbol of the Middle Ages. It was a warring time in history and the

weapons of the day were no match for the strength of these mighty fortifications. Choosing the best strategic location, the

right design and using the strongest materials was imperative—with this

accomplished, the castle could defend its inhabitants with a favorable advantage

against large warring bands of opponents.

The South West coast of England provides us with a good variety of

castles to explore—some intact and others just skeletons of better days gone

by. Whether intact or falling down,

however, they all provide a rich history of man’s strength, ingenuity and

resourcefulness. There are obvious

strategic locations--whether along the coast, at the river’s mouth or at a

natural low area of a valley. Other

locations, while not as obvious to the casual observer, may have been chosen

because of family history, personal hobbies or

a beautiful view. Once the location

was chosen, the builders would need to decide on design and materials. The onerous job of quarrying the stone and bringing

it to location was no easy job, given the tools of the day. All these components had to be considered

before plunging forward on the arduous job of castle building.

I will focus this paper on

three castles along the South West coast of England, Corfe Castle which is north

west of Swanage on the Isle of Purbeck; Lulworth Castle, in East Lulworth, Dorset;

and Portland Castle overlooking Portland Harbor in Castleton and on the Isle of

Portland .

CORFE CASTLE

On a majestic hill in South West England stands

the shell of a magnificent castle—still standing, against all odds. Its fight not quite over, maybe its job not quite

done—its remains act as if it is still defending the Isle of Purbeck. Built of Purbeck limestone by William the

Conqueror in 1100, sits Corfe Castle—spanning over a 1,000 year-old, rich

history.

“Corfe Castle is a dramatic ruin in a dramatic setting,

standing on a steep-sided natural conical hill commanding the narrow,

ravine-like gap through the chalk ridge that defends the Isle of Purbeck.” (Castelden, 61)

The word Corfe comes from the Ango-Saxon word for ‘pass’

or ‘cutting’—and that’s just where Corfe Castle sits--at the top of a steep

hill overlooking a naturally occurring ravine.

The castle sits on top of the gap in the Purbeck Hills--to the north and

south are vast stretches of land. Its imposing location of the surrounding

lands was enough to suppress the most avid enemy. Two streams, the River Wicken and the Byle

Brook, were responsible for eroding the rock and causing the gap that allows

passage to the southern section of the Isle of Purbeck. This gap was once called a “Corvesgate.” The

castle itself sits upon a steep chalk peninsula.

Corfe is located on the South West coast of England between Swanage and Kimmeridge and lies

on beds of Chalk, Wealdon Clay and

Purbeck Limestone. These beds

were laid down during the Cretaceous Age during the Mesozoic period, from 65 to

142 million years ago. The Purbeck was

laid down first, then the Wealdon beds and the earliest are the chalk

beds. These variations in sedimentology

and the resistance of each, has resulted in the deep ravine at the foot of the

Corfe castle. The Wealdon clay was the

least resistant and was eroded by the stream, resulting in the formation of the

ravine. The geology that is underlying the

surface ultimately controls how the landscape is formed.

Although the castle sits upon chalk,

it is actually made from the local Purbeck limestone which is a much sturdier

material. The limestone was quarried a

few miles to the south-

east of the castle and was an easy

material to work with as it was soft yet sturdy and could easily be cut and is

also quite resistant to the weather.

As our class climbed the hill to Corfe and roamed

the ancient grounds and ruins, we observed some interesting and telling

features used in its building. A filler

material was used within the walls to create a wider wall structure—likely for

strength and a way to build it faster.

This filler contained chert pebbles from Cretaceous chalk. There was an interesting wall with a zigzag

pattern to it—it was unusual as it didn’t match any of the other walls. The herringbone pattern of stonework comes

from a Saxon style of stone work.

Due to its strategic location, it is likely that

the site this site was used for defense from as far back as the Roman and

Bronze Age--remains of Roman pottery and Bronze Age burial grounds have been

discovered. Next to use the site were

the pre-Saxons who built a fortified site; and following them were the Saxons

who added an inner ward, a gatehouse and domestic buildings of stone and timber.

During the Saxon reign, and amongst Corfe’s many

rich and often infamous stories, is the one of the vulnerable, young King

Edward. While out on a hunting trip in

the Royal Forest in 978, he stopped at Corfe Castle to see his stepmother and half-brother. To assure himself the throne, his

half-brother stabbed King Edward who soon died after being dragged by his

horse. The dead King Edward’s

half-brother did succeed to the throne

while King Edward was named as a saint – “Edward, King and Martyr.”

Next to occupy this site were the Normans, around 1050-1100 William the Conqueror

started building Corfe and it was one of his earliest castles. He understood the great defensive location

that the hill provided. Normally castles

of the day had a motte around them.

However, the hill at Corfe provided a natural defense so a motte was not

necessary. The Normans used the Purbeck limestone from the

surrounding area as building materials for the castle which was the same stone

that was used to build the village surrounding the castle.

Corfe Castle has been considered one of England’s most important castles—indications of

this show up in the use of stone for its walls which was unusual at the time it

was built by the Normans. It was important because of its great

natural defensive location as well as it close proximity to the coast which

helped William the Conqueror stay in touch with Normandy. The design of the Keep, the inner tower, was

the heart of the Norman castle. It had only one or two ways to get in which

created a last line of defense for its inhabitants. The design, materials and location made Corfe

one of the most secure castles of its time.

It was used not only as a fortress for safety and security but also

housed the royal treasury.

Corfe castle is rich in its history: starting with the pre-Saxons, then the

Saxons, then the Normans and through the Middle Ages, through numerous kings

and queens and ending in destruction during England’s Civil War. A descriptive text taken from the 16th

century states: Corfe castle is “a very fair castle with gatehouse with fair

rooms, kitchens, cellars, halls, chambers and necessaries enclosed within a

great stone wall.” (Yarrow 1) Corfe was destroyed by orders of Parliament

in 1646 but its history lives on, and, somehow its ruined state only adds to

its intrigue.

LULWORTH CASTLE

As our class moved westward along the Jurassic

World Hertitage site on the South West Coast, we were treated to beautiful

views of Lulworth Cove and the fascinating Purbeck and Portland rock formations along this

coastline. “Purbeck is a classic place

to see how the underlying rocks control the development of the landscape and

coastline. Around Lulworth, hard bands

of Portland Limestone form a barrier to

the sea but once breached the softer rocks behind are eroded away to form a

bay.” (Dorset County Council). Visiting the Lulworth Castle provided a good opportunity to see this

stone worked in a grand way. Lulworth Castle sits inland three miles north-east of Lulworth

Cove in Dorset County and has a very classic castle design. Built between 1608 and 1610, its purpose was

for a hunting lodge, rather than for defense, and in the hopes that the

reigning King James I would visit since he enjoyed deer hunting. King James I finally paid it a visit in 1615,

and it has subsequently has hosted five reigning monarchs.

The Purbeck-Portland stone that was used to build

the castle has been quarried since early Roman times. Although it is actually limestone, it has sometimes

been confused with marble because it can take such a fine polish which leaves a

beautiful finish. Quarried from Tilly Whim Caves, Dancing Ledge and Winspit the Purbeck-Portland

Limestone provided the stone for such buildings as Lulworth Castle and Swanage Town Hall.

The Purbeck and Portland limestone was formed towards the end of

the Jurassic and beginning of the Cretaceous periods, around 142 million years

ago.

The location for Lulworth Castle was chosen

because of its beautiful location—the estate includes 20 square miles,

including some of the most beautiful coastline in England. It also includes woodlands, streams, lakes

and grasslands which provided wonderful hunting grounds. (Lulworth, Dorset, 37)

Lulworth Castle also provides the visitor with a wonderful

glimpse into castle life-- since it is more intact than the castle ruins of

Corfe Castle, one can easily image being back in history some 400 years ago

when walking its grand hallways and entering the immense rooms.

PORTLAND CASTLE

As our class moved

westward along the coastline, we were again treated to more spectacular sights at

Chesil Beach,

Portland Harbor

and the Isle of Portland. The Saxon word

for Chesil means ‘pebble’ and the beaches of Chesil were hills of vast quantities of medium-sized

pebbles as far as the eye could see.

Overlooking Portland

Harbor on the north-east coast of

the Isle of Portland in a strategic defensive location,

stands Portland Castle. Built as an artillery fort by Henry VIII in

1539, it was known as one of his best coastal fortresses. It was during this time that Henry VIII had

broken away from the Catholic Church after divorcing Catherine of Aragon and

was fearful of a threat of invasion from France

and Spain. He went to great lengths to arm England—building

and personally involving himself in the design of a series of artillery

fortifications which were named “Device Forts.”

Portland

Castle, along with Sandsfoot Castle

across the cliff, were built to protect the town of Weymouth

which today is located between two Heritage

Coasts, Purbeck

and West Dorset.

(Osprey Quay, Portland Castle)

Photo

by (c) Skyscan Balloon Photography

The appearance of Portland

Castle differs from the more

classic English castle design in that it’s built low to the ground with 14 feet

thick walls, giving it a squat appearance and, at the time, made it almost

indestructible. It stands on a cliff

overlooking Portland Harbor

and has a large round wall facing the sea and two rectangular wings on the

opposite side. Inside is a two-story

tower in the center with guns mounted on two levels facing the sea. It would have certainly been a

threatening site to anyone considering challenging its force.

The materials

Henry chose to build his castle came from the local white Portland

limestone which has been quarried from the Isle of Portland for centuries. “The Isle of Portland is a rock outcrop formed

from a block of

limestone, 4 miles by 1 ½ miles, that protrudes from Dorset

coast into the English Channel.” (Learning – Portland

Stone web site) This limestone was laid

down during the Jurassic Period, approximately 142 million years ago. Portland

Castle is still standing proudly—a

testament to its good design and fine stone work.

These wonderful relics of the past stand in all

their glory to this day—some in ruins, others intact. Corfe Castle stands majestically against the

countryside, a mere skeleton of what it was.

Parliament went to great lengths to turn it into rubble but it fought

back and stands in testimony to its shear strength. It welcomes people from all over the world to

walk through its broken walls and soak up its rich history. Lulworth Castle attracts multitudes of visitors for a day of

jousting and medieval skits—to anyone wanting to transport themselves from the

Twenty-first Century and go back in time to the Middle Ages. Portland Castle stands strong and proud over the harbor as if

still protecting England from unwanted visitors. The materials and locations that were chosen

were good choices; they served their rulers well for many, many years—whether

it be to defend or entertain. With the

invention of new warfare, these strong, old protectors were no longer the

biggest and strongest defenders--they could no longer serve their original

purpose. However, they haven’t died--these

heroic old relics still live on.

Bibliography

Books and Pamphlets:

Castleden, Rodney. English

Castles, A Photographic History. London, 2006.

Dorset and Devon County Councils. Dorset

& East Devon Coast: England’s First

Natural World Heritage Site. Costal Publishing, 2006.

Lockhart, Anne. Corfe Castle. Hants.

Yarrow, Anne. Corfe Castle. Swindon, 2005.

Weld, Wilfrid. Lulworth, Dorset. Epic Printing.

Web sites:

Castle Xplorer. Simon and Gina Robins. 2001 – 2006. August

22, 2006. http://www.castlexplorer.co.uk/england/portland/portland.php

Jurassic Coast. World Heritage Coast Trust. August

25, 2006. http://www.jurassiccoast.com/index.jsp?articleid=26755

Learning – Portland Stone; thebeasts.info.

Harrisdigital.co.uk.

2005. August 20, 2006. http://thebeasts.info/learning/portland_stone/index.htm

Osprey Quay, Portland Castle. 2004. August

28, 2006. http://www.ospreyquay.com/leisure/portland.asp

Portland Castle. Excelsior Information Systems Limited. 1999 – 2006.

August 21, 2006. http://www.aboutbritain.com/PortlandCastle.htm

Portland Castle. Best Loved

Hotels. 2006. August 25, 2006.

http://www.bestloved.com/attractions/portland-castle-in-portland-dorset-west-country-england-uk.php

Wikipedia. July 27, 2006. August 21, 2006. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Device_Forts

Home

Back to Student Project

![]()

![]()