Reconciliation and Trials

JUDICIAL SYSTEMS

“There are enormous efforts by the victims and victims’ organizations, which have been battling all these years for truth and justice. There’s an effort by relatives of the disappeared to find their loved ones and bury them. And by relatives of victims of extrajudicial execution, or survivors of sexual violence, to get justice for those cases.

And finally, thanks to verdicts at the national level, in the last three or four years there has been major advances, like the Constitutional Court ruling that says that the crime of forced disappearance constitutes a permanent crime, or the Inter-American Court ruling on the Dos Erres case, calling on judges and the justice system in general to eliminate obstacles to the trials moving forward. Or verdicts like the one from the Spanish courts, which issued arrest warrants for top military leaders as a matter of universal justice.

So I don’t believe that there’s ever a consensus in any country to “put them on trial now,” but rather efforts supported both by national and international figures and institutions that allow these cases to go forward.”

– Claudia Paz y Paz for ICTJ (International Center for Transitional Justice)

INTER-AMERICAN CONVENTION ON FORCED DISAPPEARANCE OF PERSONS (2000)

In 2000, Guatemala ratified the Inter-American Convention about the Disappearing of Persons. This treaty defined the crime of forced disappearances as a violation of international human rights law and determined that the forced disappearance of persons cannot be justified in any circumstances, not even in emergencies. The treaty also formally established that the crime “shall be deemed continuous or permanent as long as the fate or whereabouts of the victim has not been determined” (Article 3), which was monumental in Felipe Cusanero Coj’s case.[1]

THE GUATEMALAN CONSTITUTIONAL COURT (2009)

On August 31, 2009, former military commissioner Felipe Cusanero Coj was condemned by the Criminal Court of Chimaltenango to 150 years in prison. Cusanero’s trial was the first that asked the Court to determine a sentencing based on the crime of forced disappearances in Guatemala. Ultimately, Cusanero was sentenced for crimes against humanity and for forced disappearances as the Constitutional Court ruled that “It is not when the crime began, but when it stops being committed” and the fate and whereabouts of the disappeared person are established with certainty.

Reactions to the Verdict:

The day of the verdict, one woman whose husband had been disappeared in the 1980s stated that: “If we win today, it will give the rest of us the courage to start talking about the forced disappearances we have suffered.”

As Cusanero was handcuffed following the judge’s verdict, the room erupted in cries of “Que viva la Justicia en Guatemala” (“Long live justice in Guatemala!”).[2] [3]

INTER-AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS- CASE OF BLAKE V. GUATEMALA (2009)

On January 22, 2009, the Inter-American Court of Human Rights determined that based on previous merits and reparations Judgments from 1998 and 1999, the State is obligated to “adopt all the measures necessary” to investigate the denounced facts and to punish those responsible for disappearances and deaths. Furthermore, the Court declared that the State of Guatemala must inform the Court every six months of progress towards the identification and punishment of responsible parties.[4]

CICIG (INTERNATIONAL COMMISSION AGAINST IMPUNITY IN GUATEMALA) (2006)

On December 12, 2006, the United Nations and Guatemala signed an agreement to create CICIG as an independent body to support state institutions, such as the Public Prosecutor’s Office and the National Civilian Police. CICIG operates to strengthen the rule of law by conducting investigations on serious crimes in Guatemala, presenting criminal complaints to the Public Prosecutor, and recommending judicial reforms.[5]

CONCLUSION

These four landmark treaties, court decisions, and organizations helped to advance the human rights movement towards reconciliation for victims of the Guatemalan Genocide within the legal realm. As Maya Alvarado, the Executive Director of Union Nacional de Mujeres Guatemaltecas (UNAMG) stated, “To have these events on trial today as genocide is a significant step forward in bringing to light the atrocities that took place during the civil war, and which the Guatemalan tried to erase…But that is not possible. Indigenous people and the victims are demanding that the truth be known, that those responsible be identified as well as the degrees of responsibility.” [6]

However, it is important to note that trials can also be psychologically straining to victims. According to O’Connell in Gambling with the Psyche (2005), impunity for perpetrators can cause victims to doubt the legitimacy of the criminal justice system and to feel that their experiences have been invalidated. Furthermore, the long, complicated, and sometimes condescending process of judicial proceedings can cause victims to suffer new abuses, such as reprisals or harassment. Finally, the length of the trial itself could impede on the professional lives of victims, as work schedules often conflict with the ongoing trial procedures.

FOOTNOTES

1. Inter-American Commission on the Forced Disappearances of Persons

2. Disappeared but Not Forgotten: A Guatemalan Community Achieves a Landmark Verdict

3. Asian Federation Against Involuntary Disappearances

4. Order of the Inter-American Court of Human Rights* of January 22, 2009 Case of Blake v. Guatemala

5. A Wola Report on the CICIG experience the International Commission Against Impunity in Guatemala

6. Guatemala Genocide Trial – Women Seeking the Truth

GOVERNMENTAL ACTIONS

DAY OF DIGNITY

The Guatemalan Congress approved Decree 06-2004, which has established a National Remembrance day (February 25th) for victims of the genocides. [1]

GUATEMALAN NATIONAL REPARATIONS PROGRAM (NRP)

“The Guatemalan National Reparations Program (NRP) was created in 2005 as a result of the recommendations of the UN-sponsored Commission for Historical Clarification. The program compensates victims’ families with $3,000 (US) for each victim. For example, when a family from the department of Q’uiche (where 45% of the massacres took place during the internal armed conflict) files for compensation for the murder of their father, their case is reviewed, and if accepted, they receive this sum of money.”

“There are several criticisms of the NRP program. As one massacre survivor said, “What amount of money can compensate for the loss of my son?”[2]

THE HUMAN RIGHTS COMMITTEE HAS MADE GREAT PROGRESS IN INDIGENOUS RIGHTS, HOWEVER, THERE IS MUCH WORK TO BE DONE STILL:

“In addition to the criminal prosecution and punishment of those responsible for human rights violations during the conflict, it was also necessary “to know the truth” in order to make way for remedial measures such as reparations, Mr. Rosenthal stated. The national compensation programme, the Peace Secretariat and the Presidential Commission for Human Rights had been integrated to enable that process.” [3]

“Human rights and victims organizations in Guatemala have worked tirelessly to achieve important victories in the fight against impunity, but much remains to be done to achieve accountability and redress for violations during three decades of internal armed conflict. ICTJ has worked here to assist with reparations and criminal justice initiatives.”[4]

Governmental Acknowledgement

- President Alvaro Arzu (1996-2000) apologized for the role of the government in past abuses

- United Nations Truth Commission condemned US role in Guatemalan dirty war; Bill Clinton expressed regret for US governmental support

- President Perez Molina (2012-2015) refused to acknowledge that a genocide had occurred

FOOTNOTES

1. INTERNATIONAL OR HYBRID TRIBUNAL INTER-AMERICAN COURT OF HUMAN RIGHTS

2. Guatemalan reparations program for civil war victims’ families about more than compensation

3. Major Progress Made in Human Rights Protections since Guatemala’s Peace Accords 15 Years Ago, Although Much Work Remains, Human Rights Committee Told

4. Background: Justice Delayed

TRUTH COMMISSIONS

“Truth commissions exist for a designated period of time, have a specific mandate, exhibit a variety of organizational arrangements, and adopt a range of processes and procedures, with the goal of producing and disseminating a final report, including conclusions and recommendations” [1]

The use of truth commissions, like any other form of justice, have been used to bring some sense of justice and closure to the survivors in Guatemala. Commissions like those of the United Nations Commission for Historical Clarification have sought to bring truth and healing to citizens in Guatemala, as well as attempt to publicly hold the Guatemalan government accountable for the mass atrocities that occurred there. While truth commissions have done significant work to elicit truth and bring justice to the people, it must be recognized that the use of truth commissions alone cannot be solely depended on for the enactment of justice. There is a critical importance in recognizing that there are many factors that go into the execution of a truth commission, including but not limited to: The different groups that are participating in the truth commission, the group organizing and carrying out the commission, and the voices that become dominant in storytelling in the duration of the commission. To use the word “storytelling” is another important concept on its own as well. The details of mass atrocity– the pain, suffering, and understanding of what happened in Guatemala exists as more than a statistic, a set of facts or solid detail of history. It exists in the living narratives of people, and their memories.

It’s difficult to understand the interpretation of the armed conflict from just one perspective. The stories of many survivors come in the stories of their self-defense as often as their stories of witnessing violence.

One woman, Fabiana Ordóñez, an ex-guerilla community member from Santa Anita tells of her involvement in the armed conflict:

“When I joined the ORPA guerilla, that was on May 10, 1982… I was 24 when I joined up in the war…That is why I made the decision to go and fight in the mountains, for a change to take place in Guatemala… so that there is equality so that there is no exploitation…”[2]

Because the Guatemalan government has never acknowledged the responsibility of the death, disappearances, and other acts of violence in the armed conflict, the denunciation of the government in truth commissions was a common thing Eldelberto Torres Rivas, a sociologist, remembers the reaction to the genocide by many sectors:

“The work of the army was applauded by civil sectors, by the press, by businessmen, politicians…” [3]

Both commissions expose narratives of the harm to the Guatemalan people that the government has caused. We’ve found two main truth commissions that were used in Guatemala– one of them under the Roman Catholic Church and one under a United Nations mandate.

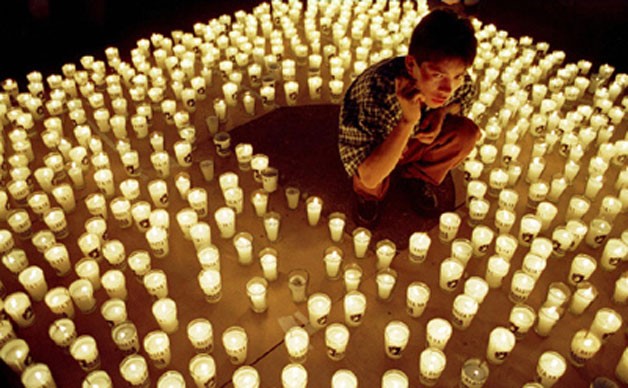

Demonstrations to remember the death of Monsignor Juan José Gerardi Conedera in 2013 and to urge the continued trial of Rios Montt[4]

The first Truth Commission was under the Roman Catholic Church under the Recovery of Historical Memory project. The byproduct was a report titled Guatemala, Never Again (REMHI, 1998).

“These reports allowed us to have a diagnosis of what had happened in Guatemala…All this has been like an investigation which seeks to dignify the memory of the victims and to have the Guatemalan social fabric rebuilt, and to allow the present and future generations to know what happened during the war so that this war may never happen again…” – Nery Ródenas Director of the Human rights Office of the Archbishop of Guatemala[5]

This report was released two years before the signing of Peace Agreements between the Guatemalan government and the Guatemalan National Revolutionary Unity (URNG). The Office of Human Rights of the Archdiocese (ODHAG) started the truth commission to “collect testimonies on human rights violations in Guatemala”. But two days after, Monsignor Juan José Gerardi Conedera was assassinated after the submission of Guatemala Never Again Report. Although reports from the commission allowed survivors to tell their stories, it’s clear the Guatemalan government refuses to acknowledge the violence that was at the hands of the government.

“They [the Guatemalan government] wanted to leave it clear that peace had been signed, but the possibility of assuming responsibilities hadn’t.” –Nery Ródenas Director of the Human rights Office of the Archbishop of Guatemala.[6]

The full version of the REMHI report can be found here on the Recovery of Historical Memory website.

More information can also be found on via Guatemala: Nunca Más and Oficina de Derechos Humanos del Arzobispado de Guatemala

The second truth commission was mandated by the United Nations, Commission for Historical Clarification (Comisión para el Esclarecimiento Histórico). From it, the report Guatemala: Memory of Silence (Guatemala: Memoria del Silencio) emerged.

While the United Nations-sponsored truth commission allowed the voices of those who were affected by the armed conflict to emerge, once again, the government denied all allegations of governmental responsibility of the violence committed.

“We wanted to talk with the government of Guatemala to carry out a process of reconciliation, but they did not receive our testimony. They told us we had not seen anything of what happened in our country”– J Francisco Soto, Director Centre for Human Rights for Legal Action[7][8]

In the report, commissioners report their findings, including spoken testimonies of the violence in Guatemala. Otilia Lux de Cotí of Guatemala– one of the three commissioners for the Commission for Historical Clarification describes some of the evidence in a UN Guatemala Press Conference in March of 1999:

“The Commission’s identification of about 630 sites of massacres perpetrated by the Government had led it to prepare a legal study”[9]

The 84-page report details findings by three commissioners– one woman of Mayan descent and two Guatemalans, chaired by German law professor, Christian Tomuschat, of Berlin’s Humboldt University.

A few prominent conclusions of the report are as follows:

“In total, the Commission conducted 7,200 interviews with 11,000 persons cataloging the interviews in a database. Declassified information from the U.S. government was included in the data.”

“The total number of people killed was over 200,000; 83% of the victims were Mayan and 17% were Latino.”

“State forces and related paramilitary groups were responsible for 93% of the violations documented” (Final Report, English Version, para. 15).”[10]

The full report of Guatemala: Memory of Silence (Guatemala: Memoria del Silencio) can be found here.

Because of the publication of the report, the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights publicly condemned the state of Guatemala. Since the publication of these truth commission reports, various NGOs have put pressure on the Guatemalan government to acknowledge and reconcile the violent harm that they have caused. Since the publication, Guatemala’s President Arzu apologized publicly but made no mention of intended follow up or attempt to reconcile the genocide. While the process of talking about the violence and group discussion of the experiences of Guatemalan citizens in no way compensates for the damage done, it is a small start to the healing of Guatemalan society.

FOOTNOTES

1. Pluralism and Particularity Within the Human Rights Paradigm

2. Guatemala: Rescuing the memory

3. Guatemala: Rescuing the memory

4. @NISGUA_Guate

5. Guatemala: Rescuing the memory

6. Guatemala: Rescuing the memory

7. Guatemala: Rescuing the memory

8. Guatemalan Genocide

9. Guatemalan Genocide

10. Truth Commission: Guatemala

11. Guatemala: Rescuing the memory