One of the first things that a person will notice about echinoderms is their radial symmetry: a generally round shape with

equal parts radiating outward from a central portion like spokes from a wheel. While radial symmetry is most obvious in

cnidarians (e.g. sea anemones and jellyfish), echinoderms possess a special type of symmetry that sets them apart from

the cnidarians and places them into a seperate classification: pentamerous secondary symmetry. Pentamerous simply

means the parts of their bodies are based on fives or multiples of fives (e.g. the arms of a sea star or the body tentacles

of a sea cucumber); it is the secondary aspect of their symmetry that places them into a similar classification as chordates.

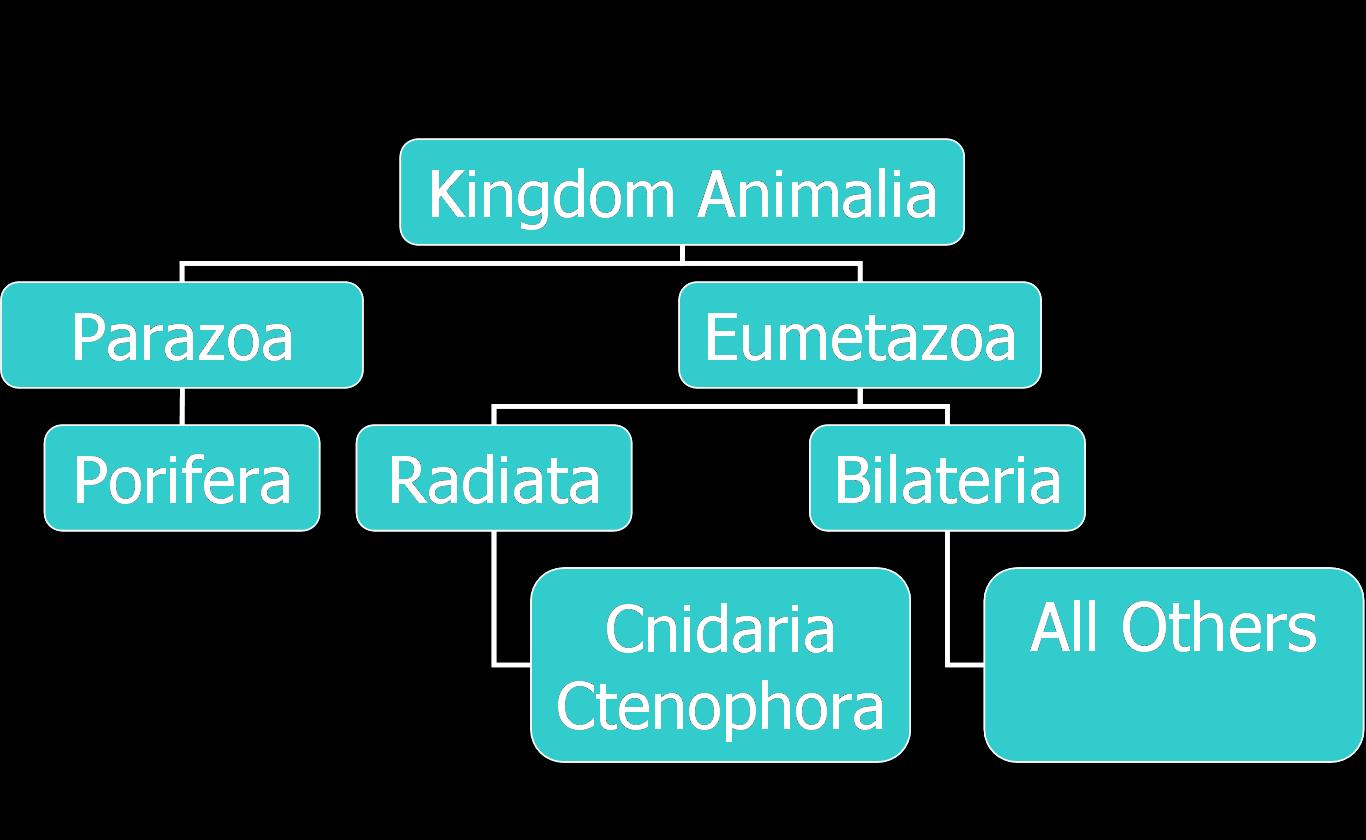

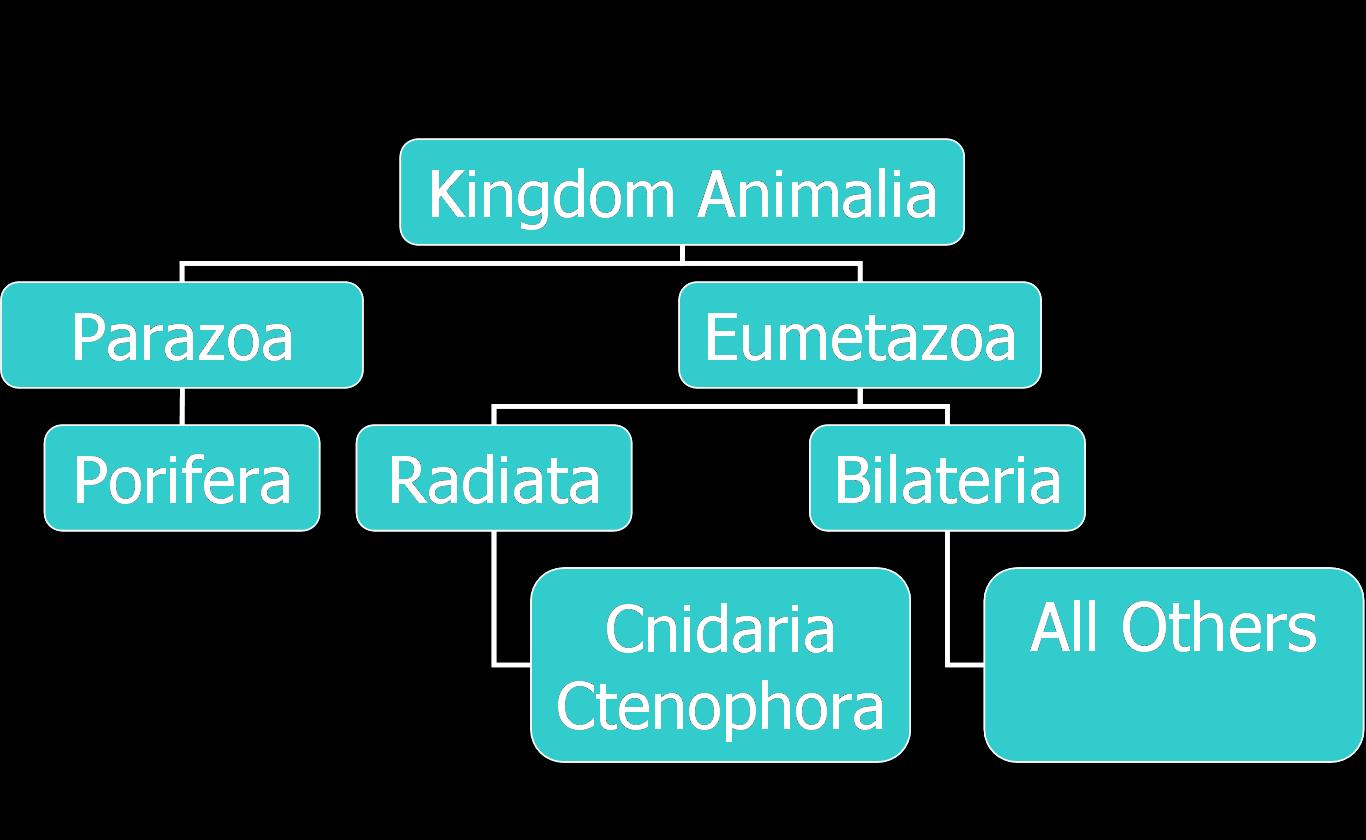

The classification of animal life begins with the division of parazoans, animals with no true tissues, and eumetazoans,

animals with a tissue level of organization. Only marine sponges of the phylum Porifera are parazoans, all others are

eumetazoans. Eumetazoans are further divided into radiata and bilateria, animals with radial or bilateral symmetry and it

may surprise some to learn that echinoderms are, in fact, classified as bilateria.

So how can this be? There are actually several reasons. Most importantly, while adult echinoderms are basically radial,

their larvae are, in fact, bilateral and their radial symmetry is something that develops when they metamorphosize into

their adult forms. Their radial symmetry is an adaptation to their lifestyle which is why it is known as secondary radial

symmetry. There is an additional reason, dealing with the number of germ layers during embryonic development but see

the section on Reproduction for more information.

The body of an echinoderm has no anterior side, no posterior side, no left and no right; only an oral side

and an aboral side (literally mouth side and not mouth side). They have a well-developed coelom (body cavity), a

complete digestive tract, and an internal skeleton of calcareous plates (one can look at a sea urchin and wonder how

their test can be considered internal, but it is actually covered by a thin layer of ciliated tissue making it internal).

Echinoderms have no circulatory system, no true respiratory system and no central nervous system (in other words, no

brain, only a nerve net that allows them to react to stimuli). Gas exchange is handled by diffusion across the skin and the

fluid within the coelom transports oxygen to the tissues and carries the wast products away.

The most unique feature of echinoderms is their water vascular system. This is a type of water hydraulic

system that aids the animal in locomation, feeding, and defense. The system consists of a central ring canal with radial

canals extending outward from it into the arms or other parts of the body. Branching from each radial canal are hundreds

of hollow, muscular tube feet that are also connected to bulb-like sacs known as ampullae. Muscles extend and

contract around the ampullae, forcing water in and out of the tube feet, thereby lengthening and shortening them

and moving the animal.

Diagram of the internal structure of a sea star showing the water vascular system.

Picture from Marine Biology by P. Castro.

“This webpage is part of the UWT Marine Ecology 2008 Class Project” : http://courses.washington.edu/mareco08