In close reading of feminist poetics, reoccurring themes involving the social and the political formations of Western culture emerge. Authors such as Susan Howe and Joan Retallack focus on the marginality and inequality of certain groups in society using unconventional methods. Through poetics, Howe and Retallack present us with the tools to better understand the complicated and confusing contemporary world. Susan Howe uses history as a way to merge the private and the public spheres in order to reconstruct social hierarchies, while Joan Retallack deconstructs social hierarchy with chance mechanisms in order to challenge the existence of marginality and bilateral domination in society altogether.

First, it is important to examine what is meant by the public sphere, and why it is useful conceptually for understanding Western culture. Jurgen Habermas was the first philosopher to introduce the idea of the private sphere. Habermas related his theory most closely with the western world from the 18th century on. According to Habermas, the public sphere consists of the social, economic and political formations in society that are established and regulated by the bourgeois classes. Also worth mentioning, is that historically as nation states began dividing governmental and religious institutions, Western culture experienced a cultural split, resulting in to two distinct realms. "The public sphere denotes specific institutions, agencies, practices; however, it is also a general social horizon of experience in which everything that is actually or seemingly relevant for all members of society is integrated" (Negt and Kluge). Habermas proposed that the development of the p! ublic sphere as a philosophical idea would encourage discussion of social economic and political institutionalism among all members of society. The public sphere is intended to be a conceptual idea that can be used as platform for critical conversation.

Since there is no actual documented theory that describes the private sphere, many scholars perceive the private sphere in slightly different ways. In poetics, the private sphere represents the authentic self. The private sphere reflects the personal and individualistic side to society, and includes the side of the life that rejects conformity and institutional participation. The private sphere embraces passion, desire and bonds between members of a society. The idea of the private sphere rests solely with the individual and personal choice. Poetics classically is perceived as a personal experiance, because it taps into the private side of the human condition. For Feminists, the idea of the private sphere is significant. The second wave feminist slogan "What is personal is political" suggests that what is private is also political in terms of womens rights concerning reproduction. The right for women to govern over their own bodies is a personal decision, yet also pub! licly directed by laws developed by political institutions. The private sphere is always in coordination and conflict with the public realm. While the public sphere is considered a social construct rooted in the idea of modernism and social hierarchy, the private is not as easily explained by the rules of practical logic or science. Women have classically been associated with the private realm and have historically found themselves at odds with the male dominated social hierarchy that controls public sphere.

Since the beginning of the scientific age,logic has divided western culture in terms of the public and the private. For the individual, public life consists of acting in accordance to the conventions in the society. The conventions are the general trends that people follow in order to claim status, live well, or perceive themselves as living well. Written history often reflects these ideals and as a result tends to reinforce systems of oppression and social stratification, because history is recorded by groups who are in a position of power and possess the means to carry out their own legacy. However, the private life tends to deny the logical and promote the passionate side of human nature. Things like love, war and Greek mythology cannot be explained in logical terms, and actually exist as indicators of our vulnerability to conventional logic. Susan Howe's writing restructures history so we can begin to see the importance of merging the private and the public in orde! r to understand ourselves and others. Howe's work suggests the importance of accepting the permeability of the boundary between public and private in order to see how they affect each other and how that understanding might facilitate progressive social change.

Susan Howe uses poetics as a tool to promote modes of understanding of how history has marginalized groups. Susan Schultz in her article called "Editing and Authority in Susan Howe," explains how Howe revises history in order to tell a particular story that highlights the negative aspects of colonialism and imperialism. Schultz describes Howe's methodology by saying, "She doesn't attempt to step outside tradition, but to redescribe and reframe an existing one in such a way that it admits women" (Schultz142). Howe brings attention to marginalized women in Pierce-Arrow. Susan Howe gives authority to women by inserting herself into the text as an historian and an editor. Howe writes from a realist perspective by saying, "/There are realities independent of thought/" (Howe59). The line from Pierce-Arrow infers that the realities of the contemporary world do not always serve everyone within a society justly, despite advancements in technology and science. To ! bring marginality to the forefront as a concern of modern civilization Howe dedicates part of Pierce-Arrow to women such as Mrs. Pierce, who leads a private existence as the mysterious wife of the famous logician, C.S. Pierce.

Howe represents C.S. Pierce as a marginalized figure. Pierce is a genius, yet Howe presents him as fallible. In Pierce-Arrow Howe rattles off a list of Peirce's achievements and failures in a way that comes off as humorous and sarcastic. Howe shows that Peirce has personality attributes that mainstream society of the time deemed unacceptable. When Howe writes Peirce she is trying to humanize him, which is something that logic cannot explain and history often forgets to do. This is where Howe attempts to merge the private and the public spheres. Pierce-Arrowexposes that the private life of the Peirces is in stark conflict with C.S Peirce's position in society as a logician and a figure of philosophical rationality.

Howe plays with reader's perception of Charles Peirce. Howe's style confronts conventional modes of valuing others. Howe showcases Peirce's work in various ways. Howe collages Peirce's notes to embody diverse ways to look at Pierce's work. In "'The Pastness of Landscape'; Susan Howe's Pierce-Arrow," Peter Nicholls says, "Howe is especially interested in the 'unofficial' Peirce as she discovers him in the huge, neglected manuscript collection in the Houghton Library, the Peirce, that is, whose papers frequently have an unexpectedly graphic and comic quality"(Nicholls445). Howe's intimate relationship with Peirce's work and her decision to publish her research in this way shows her determination to make the Peirce's private life public. Howe prints Peirce's notes in Pierce-Arrow. The scribbles on paper denies the reader the choice of simply accepting or denying C.S. Peirce's genius, but to see Peirce as indisputably human. While Howe is humanizing Peirce, she is c! hallenging conventional society's tendency to qualify achievement with propriety.

Susan Howe takes C.S. Peirce's life and starts from the outside, with his position in the society, and works inward towards the personal. However, Howe starts with the hidden side of Juliette Peirce and works outward. Howe writes the history of Peirce's wife, Juliette to emphasize marginality. Juliette is a mysterious figure who lives an isolated existence. Juliette is a retreating figure. Howe depicts Juliette is a woman in history that has all been forgotten because she had been denied a position of deference in the first place. So Howe takes Juliette's private life (as much that is known about it) and writes it to raise questions surrounding gender inequality in the public sphere. Howe reorganizes the information about the Peirces in a way that promotes discussion. There is a connection between Juliette and Howe. Schultz writes, "Howe's authority stems, therefore both from a sense of being a member of an oppressed group whose power can only come from a solidarity, a! nd, paradoxically, from her status as representative of the dominant culture: white, historical rather than mythical and editorial"(Schultz143). Juliette symbolizes Howe's sense of captivity and interest in empowerment.

Howe transcends beyond feminist discourse when she includes Greek mythology in her text. In the Greek myth, the passion of war and the human capacity for brutality defies all logic. So it is clear that Howe is playing with language to challenge the reader into discussing the dichotomy between passion and logic. In Western culture the passionate side of life is frequently hidden from public view. The social formation of western society demands a level of conformity to ideals that promote allegiance to economic and political constructs. Howe is in her own way trying the humanize logic used in the public realm by merging the private and the public. "Lectures our perceptions/ somehow fail for failing /perceptual knowledge of /"pure experience" no two/ "ideas" of future selves/ One explicit knowledge" (Howe53). Pure experience seems to denote the private, while ideas of future selves seems to imply how individuals see themselves reflected in the public eye, e.g. social sta! tus and position in relation to the social hierarchies. Howe repeats variations of the word perception to show that there are conflicts when it comes to easily altering the public landscape.

In raising the topic of perception Howe presents us with a dilemma. The brutality of it all is that perception keeps us from ever wholly experiencing things in the same way. Poetry holds different meanings for everyone based on values, beliefs and life experience. These things direct perception. Howe uses history to exemplify this idea by showing inadequacies of the way that history has been recorded from the point of view of dominant classes and those in power. Howe suggests that history cannot be written to exactly replicate past events. This "Secondness" as Howe calls it is the idea that we always have an indirect relationship to the actuality of fact. Howe suggests that there is way to transcend societal inequalities by exposing ourselves to Secondness, which can result in the unpredictability of change. Nicholl's is interested in Howe's triadic form of perception; Howe's idea of Secondness is the feeling and struggle with actuality of facts. The indirect relatio! nship between readers and the historical figures such as the Peirces gives Howe as quoted by Nicholls "Another language, another way of speaking so quietly always there in the shape of memories, thoughts, feelings, which are extra-marginal, outside of primary consciousness, yet must be classed as some sort of unawakened finite infinite articulation" (Howe qtd. in Nicholls 447-448).

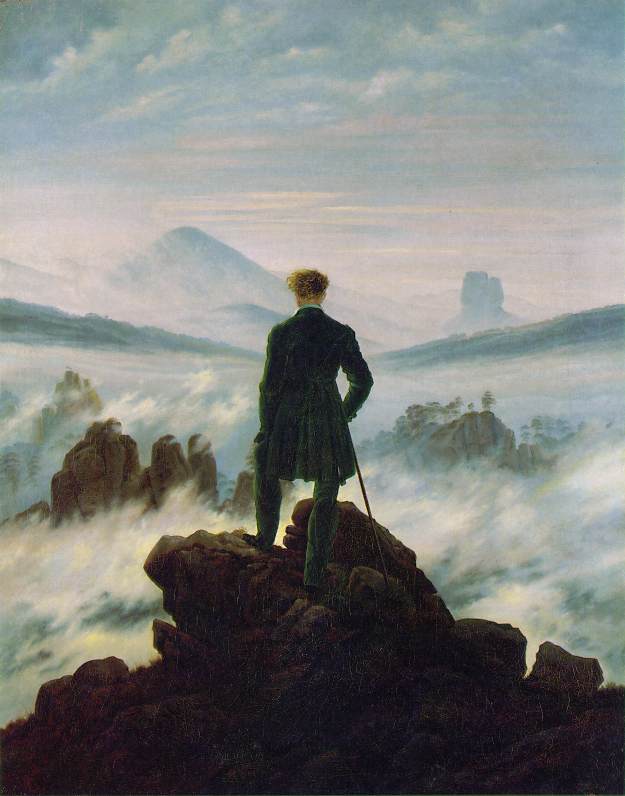

Secondness could be seen as an invitation into the private sphere. Nicholls makes the comparison between Howe and the work of Caspar David Friedrich. The figures in the Friedrich's paintings describe Howe's Secondness.

The figure in the painting shares an indirect relationship with the viewer. The viewer shares in the experience of the figure in the art. However, the viewer is blocked from the whole experience. The viewer is reminded by the presence of the figure that they can never completely see the landscape in the way that the figure does. Nicholls writes, "What we experience is not, of course, the past itself, but, as Angelika Rauch puts it, "an unknowable scenario of the past which resonates in the present situation" (Rauch qtd. in Nicholls 448). Whether it be through painting or Pierce-Arrow, Secondness is a special relationship to figures from the past. It is through the process of Secondness that the private sphere merges into the public realm.

The way that history has been recorded continues to oppress and dehumanize. History is presented in a way that positively reflects the attitudes of social hierarchies. Through Pierce-Arrow, Howe is encouraging rewriting and revision of history to challenge conventional attitudes. Howe uses alternative methods of writing in order to adjust perceptions surrounding the ethical and the social in a way that is meant to be a personal experience, yet also invoke political agency. The constellation experience of Pierce-Arrow demands that readers search for connections, associations, and truths that may feel strange and unfamiliar. Howe writes in a way that resists oversimplification of her text. We must read, discuss, and analyze the words in order to extract meaning.

Joan Retallack also requires her audience to adjust their conventional perceptions of literature in order to find meaning. Retallack writes from the poem Afterrimages, "no future tense in dreams/ (poetry eludes genre as well)."(Ratallack7) While both Howe and Retallack are promoting social and political advocacy, Howe is rewriting history to challenge traditional modes of viewing the past, and Retallack takes a more deconstructionalist approach towards challenging cultural principles that tend to shape the future. An explanation of how deconstructionalist principles can be useful in examining literature to create advocacy for challenging social hierarchies would be best described as a process of evaluating text and literature. Deconstructionalists claim that the problems in western society can be sorted out by emphasizing and disputing unfair dominance of hegemonists and the way that they influence literature and mass cultural views of history.

The contemporary world has dramatically changed in recent history and Retallack points this out in her article "Essay as Wager," by saying that, "The sudden interconnectedness of the planet via satellites and the internet has brought on a cascade of unforeseen consequences, September 11, 2001, was a paradigmatic swerve, wrenching a parochial "us" into a new world without borders" (Retallack1). Retallack is talking about how globalization and technology has changed the social and political landscape. Retallack wages that it is important to break down barriers set by current systems of social and political formation. In her writing, Retallack discusses that there are familiar patterns of existence that can influence public life and keep members of society from challenging the status quo. It is so ingrained in western culture to follow rules and trends set by social hierarchies that it makes it nearly impossible to raise consciousness without using techniques that are tru! ly revolutionary.

Joan Retallack sees that our chaotic world can cause us to revert back to certain ingrained modes of thinking. Under pressure, society seems to return to its most comfortable standards of living. Retallack uses the example that after 9/11 the US experienced a wave of conservative backlash against immigration, minority rights, and free speech. The slumping economy also seemed like an emerging threat to American's standards of living. The contemporary world is rapidly changing and requires radical new ways of thinking. Retallack's answer is Poethics, which is philosophical poetry that could be as socially instrumental as prose poetry. Retallack adds, "These mixed genres are the best way I know to make sense of the kind of world in which we live" (Ratallack4).

Retallack feels that perception of history more like a mirrored image of ourselves rather than a second hand experience. Retallack's perception of history as an afterimage is comparable to Howe's Secondness in the way that it promotes a viewing of history that acknowledges its limitless possibilties in perception. However, Retallack is interested in the temporal image that gets imprinted on the past and vice versa. The afterimage comef from is staring at an object and looking to another and seeing the residue of the first image projected on the latter object. If it is possible to see beyond our own afterimage Ann Vickery writes, "We might then see the past as not only reflecting our own (self-supporting) fantasies but as constraining the fragments of the Other" (Vickerey171). Vickerey expresses that an awareness of self perception is vital in exposing inequalities within society in relation to certain groups, which Vickery poses as the 'Other.'

The Western world is built on male dominated social and political hierarchies that have constructed the patterns of knowledge that culture is based on. What lies beyond Western culture's concept of knowledge is the Other. Women could be seen as an example of the Other. Women are left out of history, as well as current social and political constructs. Women have been and remain mostly captives of the private sphere. Retallack writes in the poem Afterrimages, "/womendressedlikemenpretendingtobewomen./"(Retallack8) This line shows the dichotomy of the female position in society. Neither the past or current social and political formations of the public sphere have accurately reflected feminine intellect. Women are historically and temporally locked in the private sphere. The formation of the public sphere keeps women from participating in a way that is authentic. Retallack uses Chaucer to reflect a historically female perspective. This is Retallack's way of promoti! ng a gendered history. Vickery points out that, "In the Wife of Bath's story, Chaucer challenges the cultural assumptions about femininity otherwise raised in the pilgrims' narratives" (175). Popular and historical images of women are almost always publicized in association with the personal such as the home, relationships, appearances and never in terms of political and economical structures of our time.

Merging the private sphere with the public is fundamental in liberating women from the structural inferiority and advocating greater participation in sorting out major global environmental, social, and political issues. Joan Retallack represents us with chance procedures as way of taking advantage sudden traumatic events as an opportunity for women to surface as activists against economic and political domination of homologous classes. Retallack feels that the modes of the public sphere are so ingrained in our decision making processes that real societal change can only develop out of spontaneous events and chance procedures. In her writing, Retallack reinforces the idea of chance procedure for the exact reason that, "Western modernity has tended to reject the presence of chance in the world because it takes control away from the knowing subject." (Vickerey172) Vickerey points out that Joan Retallack places chance procedures in a positive light, and should not be und! ervalued in terms of usefulness.

Chance procedure presents the opportunity to break away from old habits and conventional attitudes. When societal rifts occur society finds itself on the edge of chaos. During fearful and unpredictable times society reverts back to traditional modes of thinking based on a history that is narrowly presented from the point of view of dominating groups. To break this pattern there must be a proactive effort to embrace the chaos. Retallack writes in "Essay as Wager," "To wager on a poetics of the conceptual swerve is to believe in the constancy of the unexpected-source of terror, humor, hope" (Retallack4). As Americans continue to face terrorism more emphasis should be put on understanding the dynamics of the aggression rather than focusing on how to barricade ourselves against it. Our increasing global environment prevents us from old methods of military might and economic superiority to solve problems.

Where the institutional support of the public sphere fails to protect against the darkest sides of human behavior, Retallack and Howe use poetry to create agency for social change. Poetics is a way of aligning the private and personal experiences of individuals with roles as public intellectuals. As Women, Joan Retallack and Susan Howe enlist social and political agency that is unique by conventional standards. Poetry that integrates alternative views on social and political constructs is instrumental in reaching the public mind despite the chaos of mass culture and the limiting effects of perception. Leading a socially responsible and individually satisfying existence, requires that the public and private spheres to reflect each other more effectively. Joan Retallack states, "Touching, being touched, partaking of textual transfigurations in the unsettled weathers along the personal/cultural coastlines is irreversibly compelling, incorrigibly real"(Retallack6). The ki! nd of oppositional poetics that Joan Retallack and Susan Howe engage in promotes the pursuit of an authentic self. The authentic self is the state that an individual is both aware of the public and private, and thus capable of achieving extraordinary things.

Cohen, Ralph. "Do Postmodern Genres Exist?" Postmodern Genres. Ed. Marjorie Perloff. Norman: U of Oklahoma P, 1989. 11-27.

Nicholls, Peter. "'The Pastness of Landscape': Susan Howe's Pierce-Arrow." Contemporary Literature, 43:3 (2002 Fall), 441-60.

Retallack, Joan. "Essay as Wager." The Poethical Wager. Berkeley: U of California P, 2003. 1-19.

Schultz, Susan M. "The Stutter in the Text: Editing and Historical Authority in the Work of Susan Howe." A Poetics of Impasse in Modern and Contemporary American Poetry. Tuscaloosa: U of Alabama P, 2005. 141-158.

Taylor, Mark C. "Screening Information." The Moment of Complexity: Emerging Network Culture. Chicago: U of Chicago P, 2001. 195-232.

Vickery, Ann. "Taking a Poethical Perspective: Joan Retallack's Afterrimages." Leaving Lines of Gender: A Feminist Genealogy of Language Writing. Hanover: Wesleyan UP, 2000. 167-78.

Wikipedia. November 2006. December 5, 2006. http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Public_sphere.