As we shuffle about from place to place during our daily routines we are constantly surrounded by different surfaces, surfaces that make up a whole, the ”landscape” around us. Buildings, roads, paths, water or dry ground, these surfaces or boundaries of three-dimensional objects, define the landscape. They blend from the ground plane to the sky defining space and blurring boundaries. But our true awareness of these surrounding surfaces seems typically quite minimal.

As I walked a path I have traveled many times, from Gould Court to Condon Hall, I consciously chose to observe the surfaces I passed over. As I began to record these surfaces, the sheer number of different materials and textures surprised me. Rarely could I move more than five yards before encountering another transition of surface. All pieces of the landscape around me that I had failed to recognize. This heightened awareness allows me to observe and better define through parts, the landscape I’ve been surrounded by.

Reclamation:

A once polluted and industrial wasteland is now converted into an inhabitable and welcoming place. The course of time is shown throughout the remaining structures of a time passed in Seattle’s history. The deep earthy tones and patinas brought on by years of exposure to the elements have left a curious beauty to something that was once a ruinous polluter. Although the hand of man has altered the grounds that the ruins occupy they are not the real draw. The old rusty object in a field of green has a power and mystery about it. As nature tries to take back what it once possessed we allow it. The grasses and blackberries begin to take hold of the rusty metal and their roots begin to dig in. The lake keeps watch in the background, ever mindful of the past, its spray slowly deteriorating the towers that once tried to destroy it. The red and black towers stand though, waiting in their place for the slow decay of time to take them. It’s a play of give and take, a constant battle of the elements and a reminder of the past that once was.Tian An Men Square, Beijing, China

I took these photos during my spring break in China. It is fascinating to see the changes that are happening in this place – one of the most crowded plazas in the world. Everything seems changing and moving so fast that they spring out of the focus. Except the solid wall of the ancient architecture and the policeman – they stand as firm as they are and create a sense of authority. It has been said that architecture is the most political art; it is very true here, where the North is bounded by the ancient temple and Mao’s stare, the South offers an extensive view of flat landscape, or urbanscape, teemed with activities under strict surveillance. Traffic jam, tourists, communists, cars and bicycles, monuments and movements – you can feel the pulses of China’s heart. I tend to think that social changes can be manifested through a built landscape, and a particular place in a given time period has its own expression and character that cannot be mistaken as another place. Tian An Men Square is in many ways a unique place. This photomontage attempts to capture the fleeting sense of social changes and human activities, contrasted by the apparent permanence, authority, and security we like to associate with buildings and landscape.Re-occurring Landscape

temporary ◦ impermanent ◦ brief ◦ transient ◦ passing ◦ momentary ◦ provisional ◦ transitory

The landscape of tents which comprise the Fremont Market appear every Sunday rain or shine. These tents modulate the space of 34th Street and define a temporary zone within which the market occurs. Early in the morning the vendors begin to arrive and gradually the landscape emerges. As the day goes on this space is filled with people strolling and shopping. When late-afternoon arrives the goods start to disappear into their storage containers and the tents begin to vanish. By dark the street is empty and no trace remains except an image that is held in the mind and the knowledge that next Sunday it will appear once more.

The market is formed in the street by two lines of square, white plastic tents which can be read together as linear forms or separately as individualized spaces. They modify the space in such a way that the use of the street and the way pedestrians experience it is completely transformed. Most tents face the center of the street creating a corridor or the “inside” of the market. This leaves the back of each tent facing the sidewalk which can be seen as “outside”. This re-orientation of the street is most apparent when traveling down the sidewalk where the backsides of the tents are exposed.

This exercise can be read in two ways: first, from the textural, granular, detailed surface of a tree trunk and surrounding ivy to the larger context of a landscaped slope of trees amidst a field of groundcover. This sequence can also be understood as moving in the opposite direction, from the general, easily identifiable encompassing “landscape” to the more particular, singular, and focused image of a particular surface. Ultimately, I was interested in exploring what I see as a disconnect between the macro and micro-dimensional aspects of our conception of landscape. We are very comfortable observing and studying phenomena up-close, such as when we stoop to smell a flower, admire the texture of a stone counter, or run our fingers through blades of grass in a local park. We are equally comfortable understanding landscape as a framed and quantifiable entity on a larger scale, such as the quintessential Seattle view from Kerry Park or an image of the rolling fields of eastern Washington. What is more difficult is understanding the in-between of a given landscape; what it means to traverse its contours, to absorb its intricacies in a fluid, hybrid, and perhaps even non-linear fashion. This exercise does not claim to introduce such a process, but rather aims to show that—even while maintaining focus on a singular point—a simple vertical and horizontal displacement yields an incredible richness and variety in texture, scale, and perceived depth. If these perspectives could be multiplied, juxtaposed, and sifted through in a dynamic way, they might begin to approximate the power and the potential in the idea of landscape. Just as in architecture, this power is not derived from snapshots, whether large or small, but rather from a persistent and participatory discovery of what it means to move through a space, to respond to its details and its larger gestures simultaneously, and in understanding that a landscape—just like a building—is an active entity, charged with meaning, simply waiting for someone to engage it.

One relationship of landscape and architecture is found through the paths that connect them. There are many types of paths to architecture.

There are aisles, arteries, avenues, beats, beaten paths, boulevards, byways, crosscuts, directions, drags, footpaths, grooves, highways, lanes, lines, passes, passages, pathways, procedures, rails, roads, roadways, routes, ruts, shortcuts, streets, strolls, terraces, thoroughfares, tracks, trails, walks, walkways, and ways.

Most paths cut through the landscape and lead to architecture and the built environment. Some lead to other landscape. We navigate through the landscape either on foot, bicycle, or motorized vehicle on any type of path. These paths could be thought of as the links between destinations. The destination is a piece of architecture.

Some paths provide context for architecture. Roads lead to highways and freeways which lead us to streets then driveways and finally to buildings.

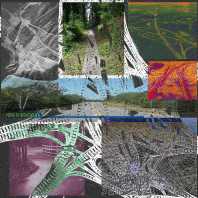

Unfortunately some paths can dissect and coat the natural landscape with unnatural and impermeable surfaces. But other paths are not so obvious in the landscape. When viewed aerially it is easy to see how they can define the landscape. Historically, paths have made travel through natural terrain easier. The ability to pass through the landscape has given the opportunity to attain natural resources in order to construct buildings. Zigzagged on the sides of mountains there are roads that lead to clear-cut forests. The road home becomes a nostalgic link to the architecture we grew up in. There are many ways in which paths relate architecture to the landscape.