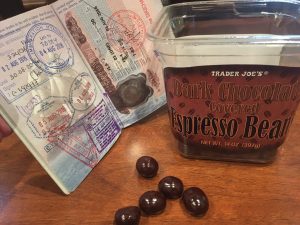

“Your food’s been around the world and I, I, I…” – Photo by Chef Michael

When we think of the types of exports that, in this modern 21st century day and age, significantly shape or change the course of a nation(s), food is not at the top of the list. Most attention, especially in common news media, focuses on the big post-industrial power markets of things like oil, gold, coal, copper, diamonds, weapons, electronics and mechanical manufacturing. And while the international trade of all of these are undoubtedly the main collective driving force of today’s global economy and international politics, as well as making up a huge portion of a nation’s job market, it is the international trade of basic commodities necessary to sustain life that create a foundation allowing the former.

A nation cannot sustainably flourish economically, politically, or socially, in any of the big-ticket resource markets if that nation’s people aren’t getting the food they need (or want). In a way, there are a lot of similar dynamics today in the world food market as there were in colonial times up through colonialism of the first part of the 20th century. The richest and most politically powerful nations, one way and from someplace or another, keep their desired food imports coming in. Nations, that over the past 100 years formed and gained sovereignty, whose economic histories are mainly of the food export-driven variety, are still fundamental in the overall global economy. In addition, many countries (in the tropics are prime examples) that have undergone development of major nonrenewable-resource market economies also simultaneously contribute to the arguably more necessary markets of agriculture.

Traditionally “exotic” food items in American and European supermarkets, such as sugar, chocolate, coffee, tropical fruits, vanilla, coconut, cashews, have only gained in popularity, with levels of consumption seeing exponential growth that correlates with population growth. The top consumers of these food items are those importing them. In our class we did a contemplative practice on a simple little piece of chocolate. But as I thought about the chocolate considering what we’ve studied, the food ceased to be a simple, delicious item. There is a complex story behind those chocolate products in the grocery store, one that involves politics and state-society relations, multiple economies of multiple countries, and varying levels of social welfare. The “fair-trade” (versus free trade) concept stands out, and so does thinking about all that went into getting that “American” packaged product on the shelf.

Perhaps you are a Whole-Foods-going stereotypical West Coast outdoorsy type stocking up on those Clif Bars for a summer road trip. One yummy bite might contain cacao from Dominican Republic, palm kernel oil from Nigeria, coconut from India, sugar from Brazil… you get the point. When considering what all of those food-exporting countries’ politico-economic histories have in common, it is obvious to see they are very different than those of the Global North. Most of the states are relatively young in a post-colonial sense, and while many of them also have major non-food export economies, it is at the most basic level the economy and journey of food that connects each nation to one another.