Windows to Research: Increasing Children’s Self–Esteem Through Supportiveness Training for Youth Sport Coaches

Adapted from Smoll, F.L., Smith, R.E., Barnett,

N.P., & Everett, J,J. (1993). Enhancement of Children’s Self-Esteem Through

Social Support Training for Youth Sport Coaches.

Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 602-610.

Historically, few aspects of personality

have received greater theoretical and research attention than self-esteem.

Although self-evaluations may relate to specific areas of experience,

such as social, academic, and athletic domains, most theorists also subscribe

to a more encompassing construct of global self-esteem that refers to one’s

generalized sense of self-worth. This

construct appears to be plausible on both theoretical and research-driven grounds.

Traditionally,

society has viewed self-esteem to be a product of social interaction. This focus can be seen in the vast amount of

previous research that has been conducted on this topic within the family and

school settings. However, a less studied

social setting that may also influence a child’s developing self-esteem is organized

sports.

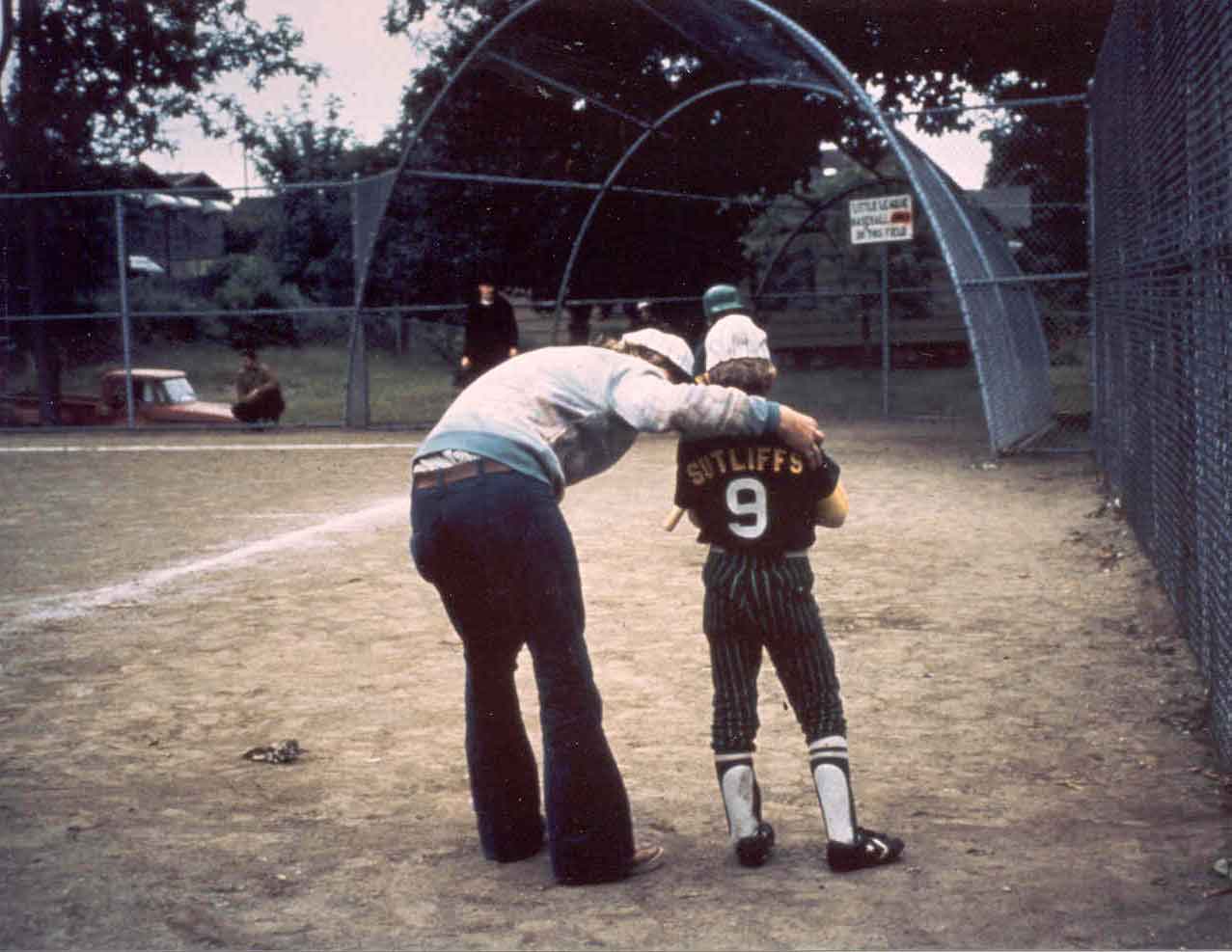

In this study,

eight male coaches of Little League Baseball players were trained in a 2 1/2-hour

preseason workshop designed to increase their supportiveness and instructional

effectiveness when interacting with the players on their respective teams (click here for a more detailed

description of the workshop coaching guidelines). As a comparison group, ten coaches from two

other leagues were not given the workshop.

To assess the effectiveness of the coach training, boys (N=152) from

all three leagues were interviewed in the preseason and postseason. In the interview, each boy filled out a questionnaire

that measured his general self-esteem. There were 14 descriptive statements on the questionnaire, each

of which was rated on a 4-point scale. Six

of the statements referred to positive attributes, whereas eight statements

were negative self-evaluations. The

entire questionnaire provides a maximum range of scores from 14 to 56 (click

here to see the self-esteem questionnaire).

______________________________________________________________________________________

Analysis

of Group Equivalence

The

mean ages of the coaches and the boys and the mean number of years of total

coaching experience is listed in Table 1. Statistical

analyses revealed that there were no statistically significant group differences

between the experimental and control coaches for any of these three demographic

variables. Likewise, after collecting

pre and postseason data for 62 boys in the experimental group and 90 boys in

the control group (72% and 78% respectively), analyses revealed no statistically

significant difference in age between boys in the experimental and control groups.

Table 1. Demographics

of Age and Coaching Experience for Coaches and Age for Boys.

|

Overall Mean Ages Coaches (years) |

40.00 (SD=6.77) |

|

Overall Mean Coaching experience |

8.89 (SD=4.64) |

|

Overall Mean Ages Little League Boys (years) |

11.39 (SD=.81) |

______________________________________________________________________________________

Self-Esteem

Analyses

Analyses of the self-esteem

measures, both preseason and postseason, were conducted for 147 boys because

five boys in the original sample did not provide data at both times. The preseason self-esteem questionnaire yielded

nearly identical means of 47.80 (SD=4.73) for the experimental group (n=59)

and 47.76 (SD= 5.76) for the control groups (n=88). The postseason means for these two groups were

48.71 (SD=5.43) for the experimental group and 47.40 (SD=6.60) for the control

groups. Statistical analyses revealed

no significant differences between the two groups in postseason means.

In addition, when postseason means were adjusted using preseason scores

as a covariant (thereby removing all effects of any preseason differences),

the postseason differences remained statistically non-significant.

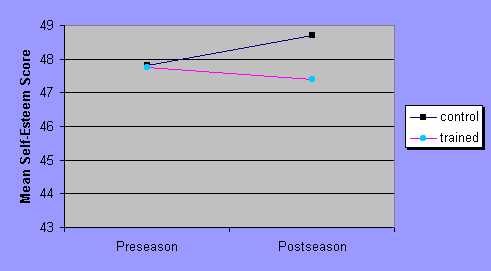

The mean preseason and postseason self-esteem scores for all samples

of boys are shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Mean preseason and postseason self-esteem scores of all boys who played

for trained and control-group coaches. ______________________________________________________________________________________

Although,

it was possible that the coach training intervention had no real effect, previous

evidence led the researchers to hypothesize that low self-esteem children might

be more responsive to variations in coaching behaviors. The previous analyses

included boys of all varying levels of self-esteem.

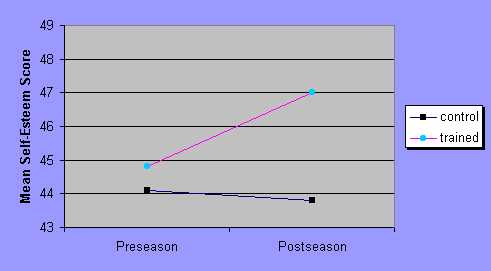

The researchers conducted additional statistical analyses in search of

potential treatment effects for the 86 boys whose preseason self-esteem scores

were below the median value of 49. The

mean preseason and postseason self-esteem scores for this subsample of boys

are shown in Figure 2.

Figure

2. Mean preseason and postseason self-esteem scores

of boys with low self-esteem who played for trained and control-group coaches.

Similar to the larger sample of all boys, in this subsample there were no significant differences on the preseason self-esteem measure between the experimental group and the control group. However, when postseason means were again adjusted using preseason as a covariate, significantly higher level of self-esteem were revealed for the boys who had played for the trained coaches (F(1,84)= 4.56, p<.05). Further analysis of these two groups revealed that scores for the low self-esteem boys who had played for the trained coaches increased significantly. However, scores for the low self-esteem boys in the control group showed no significant change.

At the end of the season the researchers

also asked the athletes to evaluate their experiences in Little League. There

were no differences between the ratings for boys who played for trained and

control coaches for 1) liking for baseball or 2) their coach's baseball knowledge.

However, the boys who played for trained coaches rated items such as

1) their fun playing baseball, 2) their liking for their coach, 3) their coach's

teaching ability, and 4) how well they liked their teammates significantly higher

than did the boys who played for control coaches. Additionally, because the

two groups were from different leagues, there was no significant difference

in their average won/loss records.

The researchers concluded that the workshops were a successful

addition to the preseason preparation for Little League Baseball coaches.

1. What

type of experiment did the researchers conduct?

2. What was the dependent variable? The independent variables?

3. The researchers took advantage of intact groups - the different little leagues.

What steps did the researchers take to show that there were not any major differences

between these intact groups at the start of the experiment? Intact groups

have the disadvantage of building possible selection confounds into an experiment.

Are there other factors that might vary systematically with the different leagues

that could be possible confounding variables?

4. There were some advantages of using intact groups (separate

leagues) rather than randomly assigning coaches to the control group or experimental

group for this experiment. What were these advantages?

5. Suppose that you serve on the Board of Directors for your local Little League and would like to convince the other board members and the volunteer coaches that the Board should sponsor a preseason workshop designed to help coaches prepare to work effectively with young athletes. How you could take advantage of the results of this applied youth-sport study to support your position?