The Romans in Britannia

Alison

Crouch

TESC

417

Summer

Quarter 2006

Dr.

Davies-Vollum

Dr.

Greengrove

The Romans invaded

and over took many lands during the rise of their empire. The goals when they conquered the lands was to

gain more land and natural resources, although the lands they conquered were

very different. It is important to note

that although the Romans changed and altered societies in the lands they conquered

they still allowed most of them to keep a certain amount of tradition.

The purpose of

this paper is to examine the development of Roman Baths in

Pre Roman Britannia

To understand what

advancements the Romans brought to

![]()

In

4000 BC, things started to change dramatically.

People began to domesticate animals and grow crops. “The earliest features we see of this time

are known as causewayed camp’s, so called because the ditches which surrounded

them are not continuous but crossed by causeways” (Westwood 2). It is likely that immigrants from the

continent initiated these changes. “One

of the results of this change of lifestyle was that, although still hard, it

did leave people with time to spare.

Thus we begin to see monuments; burial barrows (see picture 1), hedge

monuments and other ceremonial structures” (Westwood 4). The Bronze Age begins around 2000 BC. During this age, metal artifacts begun to be

used. The Bronze Age and each following century

brought continual social changes, rise in population, and changes in politics

and religious practices. “The earliest

known settlement in Dorset took place around Chesil Beach and it was from

Chesil Beach that ancient Britons collected pebbles for ammunition to use

against the invading Romans” (Westwood 3).

In

4000 BC, things started to change dramatically.

People began to domesticate animals and grow crops. “The earliest features we see of this time

are known as causewayed camp’s, so called because the ditches which surrounded

them are not continuous but crossed by causeways” (Westwood 2). It is likely that immigrants from the

continent initiated these changes. “One

of the results of this change of lifestyle was that, although still hard, it

did leave people with time to spare.

Thus we begin to see monuments; burial barrows (see picture 1), hedge

monuments and other ceremonial structures” (Westwood 4). The Bronze Age begins around 2000 BC. During this age, metal artifacts begun to be

used. The Bronze Age and each following century

brought continual social changes, rise in population, and changes in politics

and religious practices. “The earliest

known settlement in Dorset took place around Chesil Beach and it was from

Chesil Beach that ancient Britons collected pebbles for ammunition to use

against the invading Romans” (Westwood 3).

Roman Invasion of

At the time of the

Roman invasion, many different tribes inhabited Iron Age

The first

attempted invasions by the Romans were in 55 AD and 54 AD, by Julius

Caesar. The night of

The next attempt

was in July of 54 AD, again Julius Caesar landed with 50,000 troops and 2,000

cavalry; however, this time they landed with no resistance. After some successful battles and being able

to cross the

During Julius

Caesar’s time in

The Celts lived in

well organized societies with strict laws.

Most of the population lived in scattered, isolated farming communities

with granaries, storage pits, workshops, and animal pens, their villages were

surrounded by banks with wattle fencing and a ditch to keep out intruders and

marauding wild animals. Their houses

were made of wattle and daub with thatched roof or in the hills dry stone. The villages in the lowlands had earthworks

for defensive surrounding while those in the highlands had stone walls. (Watney 2)

The Celts also

had relatively advanced bronze and iron technology, and even had

goldsmiths. “The women of the tribes

spun, wove, and dyed wool to make clothing.

Men and women wore jewelry and was very proud of their long hair”

(Watney 3).

Emperor Claudius

ordered the third invasion in 43 AD. The

invasion’s success led to 365 years of rule.

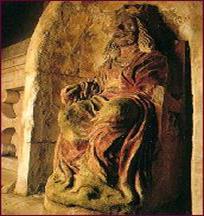

Aulus Plautius (see picture 2) was in charge of the invasion and landed

with four legions, numbering some 24,000 men and an equal number of auxiliary troops

in the natural harbor at Richborough on the east coast of

Emperor Claudius

ordered the third invasion in 43 AD. The

invasion’s success led to 365 years of rule.

Aulus Plautius (see picture 2) was in charge of the invasion and landed

with four legions, numbering some 24,000 men and an equal number of auxiliary troops

in the natural harbor at Richborough on the east coast of

The

Romans were able to tackle the tribes and their hillforts one by one, without

fear of attack by their victims’ neighbors.

Maybe if the tribes would have fought together, they would have resisted

the Romans invasion, however the Romans did possess superior weapons, military

technology and strategy, and were undoubtedly better-trained (Westwood

18). “At the time of its invasion of

Britain, the Roman army was the most disciplined and efficient killing machine

that the ancient world had ever known, and would remain so for the best part of

400 years” (Watney 6). Even with this

superior army, “it would take another 90 years before the whole of

The

Romans were able to tackle the tribes and their hillforts one by one, without

fear of attack by their victims’ neighbors.

Maybe if the tribes would have fought together, they would have resisted

the Romans invasion, however the Romans did possess superior weapons, military

technology and strategy, and were undoubtedly better-trained (Westwood

18). “At the time of its invasion of

Britain, the Roman army was the most disciplined and efficient killing machine

that the ancient world had ever known, and would remain so for the best part of

400 years” (Watney 6). Even with this

superior army, “it would take another 90 years before the whole of

Romanizing

Once the Romans

had conquered a province, the rapid construction of roads was vital to enable

garrison troops to move quickly to deal with any uprising. Naturally, the roads were also of huge

benefit to trade. Roman roads were

cleverly designed but simple to execute.

The roads were first surveyed to keep them straight. As shown in figure 1, roadbeds were dug three

feet down and twenty-three feet across.

The first layer laid down was large gravel and sand. Next, a layer of smaller gravel was placed

down and leveled. The sides were lined

with blocks and hand-carved stones.

Stones were often pentagonal in shape and fitted together to make the

top layer of the road. To ensure

rainwater would not cover the road it was sloped from the center so rainwater

would drain off into ditches at the sides of the roads. Even though the roads were dug twenty-three

feet across, the carts (and therefore ruts) were only about eight feet

across.

Figure 1 Cross section of a

Romans built towns and

roads and local industries grew and flourished.

[…] In the Isle of Purbeck we see

evidence of quarrying for stone, particularly the Portland Stone and Purbeck

Marble. These were used for major

building works and for decorative purposes.

Hard shale at Kimmeridge was extracted, carved, and turned into

decorative artifacts and jewelry. (Westwood

21)

Before the Romans

came to

“Roman legions had

two tasks: first, subdue conquered territories and then encourage the

Romanization and urbanization of the tribal nobility by allowing them to run

their own affairs and enjoy Roman standard of living” (Watney 10).

In Durnovaria the

usual trapping of Roman affluence have been found there such as mosaics,

hypocaust (central heating) systems, bath houses and roads. North of Dorchester at Poundbury we can see

the remains of a Roman aqueduct that once brought fresh water nine miles to the

people of Durnovaria. At near by

Maumbury an amphitheater was built capable of searing around 10, 000

people. No doubt, the gladiatorial

spectacles proved popular here just as they did with the citizens of

Unlike

all other Romano-British towns,

Unlike

all other Romano-British towns,

In

60 AD and the following year, a devastating rebellion broke out in the southern

part of

In

60 AD and the following year, a devastating rebellion broke out in the southern

part of

Construction of the

Baths

“Around the Sacred

Spring the Romans developed a religious sanctuary and spa, dedicated to Sulis

Minerva which was to become famous throughout the Empire. The settlement which grew out of this

unification would be called Aquae Sulis: the Waters of Sul” (Green 17). “What remains today is a remarkable sequence

of ancient, medieval and later structures that give testimony to the continuous

use of hot water here over nearly 2,000 years” (Cunliffe 1).

The nucleus of the

baths and the

The Sacred Spring

The construction of the Roman Baths began

around 65 AD with the taming of the great spring. First, the surrounding marshland was drained

and the spring enclosed within a watertight lead-lined reservoir wall. Thus harnessed, the hot waters were channeled

into a suite of baths, which formed the central attraction of an immense

leisure complex. Picture 4 shows the

Romans working on building the wall around the Sacred Spring.

The construction of the Roman Baths began

around 65 AD with the taming of the great spring. First, the surrounding marshland was drained

and the spring enclosed within a watertight lead-lined reservoir wall. Thus harnessed, the hot waters were channeled

into a suite of baths, which formed the central attraction of an immense

leisure complex. Picture 4 shows the

Romans working on building the wall around the Sacred Spring.

The Sacred Spring lies at the very heart of the ancient

monument. “Water rises here at the rate

of over a million litres a day and at a temperature of 460C” (The

Roman Baths). The spring rises within

the courtyard of the

“Isolated from the

hustle and bustle of the bathing establishments crowd, the spring would have

retrieved its primeval quietude, broken only by the echoes of the bubbling

waters and hushed voices of pilgrims come to seek an audience with the goddess

Sulis Minerva” (Green 19 ).

The

spring was the point at which our world could communicate with the god. Most people who went asking for guidance or

intervention by the goddess and after their prayers would be answered; they

would leave money or tokens of appreciation to the goddess. Since excavation has begun about 12,000 Roman

coins spanning the entire periods 1- 114th Century AD have been

found. Women also gave combs, jewelry,

brooches, bracelets, and other trinkets.

Picture 5 is of the Sacred Spring taken August of this year.

The

spring was the point at which our world could communicate with the god. Most people who went asking for guidance or

intervention by the goddess and after their prayers would be answered; they

would leave money or tokens of appreciation to the goddess. Since excavation has begun about 12,000 Roman

coins spanning the entire periods 1- 114th Century AD have been

found. Women also gave combs, jewelry,

brooches, bracelets, and other trinkets.

Picture 5 is of the Sacred Spring taken August of this year.

“More fascinating,

for what they reveal about everyday life in Roman Baths, are small scrolls of

pewter and lead on which were inscribed messages to the goddess, many of them

asking her to avenge some grievance or intercede in a family dispute” (Green

19). Some examples of these curses are

“may he who carried off Vilbia from me become liquid as the water, May she who

so obscenely devoured her become dumb […].

[Another one found read] Dodimedis

has lost two gloves. He asks that the

person who has stolen them should lose his mind and eyes in the temple where

she appoint” (Green 19). So far, there has

been 130 found written in Celtic, Latin, and cursive. The person placing the curse did not always

know who exactly did them wrong, but they were able to provide a list of suspects. It was thought that if the culprit were

named, the goddess would know and could then complete the curse (Cunliffe 20).

The

The temple became

the centre of a cult to Minerva with its own priest, the only such one in

As seen in picture 6 the

This room would

have been dimly lit without windows, with the only light coming through the

doorway and from the eternal flame.

The eternal flame was attended to by priests and continuously burned before the statue of Minerva.

This room would

have been dimly lit without windows, with the only light coming through the

doorway and from the eternal flame.

The eternal flame was attended to by priests and continuously burned before the statue of Minerva.

In the late second

century, the Sacred Spring was roofed over to create a far more mysterious

atmosphere – much like stepping into a vast, steaming cavern, its walls

suffused with a rippling greenish light (Green 18-19). At about the same time the

The

Courtyard

The

Courtyard

The

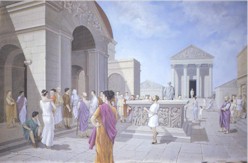

paved colonnaded courtyard surrounding the temple contained many other

religious and ceremonial buildings commemorating a pantheon of gods. Below the temple stood a sacrificial alter

bearing carvings of traditional Roman gods such as Bacchus, Jupiter and Apollo,

at either side of which were shrines dedicated to Sol, god of the sun, and to

Luna, the moon goddess (Green 21).

Picture 7 is an example of how the courtyard could have looked on any

given day the large sacrificial altar can be seen in front of the entrance to

the

The

paved colonnaded courtyard surrounding the temple contained many other

religious and ceremonial buildings commemorating a pantheon of gods. Below the temple stood a sacrificial alter

bearing carvings of traditional Roman gods such as Bacchus, Jupiter and Apollo,

at either side of which were shrines dedicated to Sol, god of the sun, and to

Luna, the moon goddess (Green 21).

Picture 7 is an example of how the courtyard could have looked on any

given day the large sacrificial altar can be seen in front of the entrance to

the

Unlike

modern religious ceremonies, Roman religious ceremonies usually took place

outside, around the large sacrificial altar in front of the

Unlike

modern religious ceremonies, Roman religious ceremonies usually took place

outside, around the large sacrificial altar in front of the

The

Great

The Great Bath was

the centrepiece of the Roman-bathing establishment. It was fed with hot water directly from the

Sacred Spring and provided an opportunity to enjoy a luxurious warm swim. “The bath is lined with 45 thick sheets of

lead and is 1.6 metres deep. Access is

by four steep steps that surround the bath” (The Roman Baths).

“The Great Bath

once stood in an enormous barrel-vaulted hall that rose to a height of 40

metres. For many Roman visitors this may

have been the largest building they had ever entered in their life” (The Roman

Baths). Niches around the baths would

have held benches for bathers and possibly small tables for drinks or

snacks.

Day

at the Baths

Although families

visited the baths, they could not bathe together. “Roman men and women did not take baths

together, not even husbands and wives.

Women usually went to the baths in the mornings, while most men were at

work. Men went to the baths in the

afternoon” (Macdonald 25). During a normal

day, the baths would have been a:

noisy, exuberant place

with: the richly frescoed walls of the Great Bath echoing to the sounds of

diving and splashing; the slapping and pummeling of masseurs at work in the

adjacent massage rooms; the puffing and grunting of weight-lifters showing off

their physical form and prowess in exercise rooms; the exhilarated cries of

patrons emerging from the intense heat of sauna into the cold plunge bath. In corridors and passageways, there would

have been joke-telling and laughter; the hushed tones of some slanderous gossip

shared; perhaps the occasional groan of the ageing legionary slowly lowering

immersing himself in the warm bath in hope of easing the discomfort of

rheumatism. There were quieter rooms

too, for the conducting of business transactions and playing board games, and rooms

for the essential rituals of daily bathing which were such vital part of the

Roman way of life. (Green 20)

Even though the baths were a place for

cleanliness and relaxation there, was more to them then just jumping into the

water and washing up. In fact, there

were five separate stages to taking a bath Roman-style. “After changing, bathers went into a very hot

room, which was full of steam where they sat for a while. Then they went into a hot, dry room, where a

slave removed all the sweat and dirt from their skin, using a metal scraper and

olive oil. To cool off, they went for a

swim in a tepid pool. Finally, they

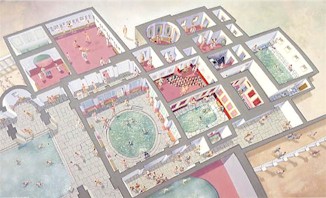

jumped into a bracing cold pool” (Macdonald 25). Picture 10 is an aerial view of what the

bathing complex at

Even though the baths were a place for

cleanliness and relaxation there, was more to them then just jumping into the

water and washing up. In fact, there

were five separate stages to taking a bath Roman-style. “After changing, bathers went into a very hot

room, which was full of steam where they sat for a while. Then they went into a hot, dry room, where a

slave removed all the sweat and dirt from their skin, using a metal scraper and

olive oil. To cool off, they went for a

swim in a tepid pool. Finally, they

jumped into a bracing cold pool” (Macdonald 25). Picture 10 is an aerial view of what the

bathing complex at

Where did the water

come from?

So far, we have

covered what

The water we are

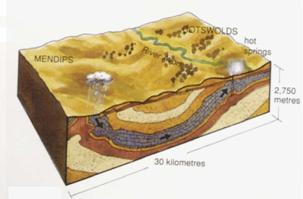

watching now was rain falling on the Mendips.

It percolated down through the carboniferous limestone deep into the

earth where, between 2700-4300 m, natural heat raised the temperature to 64-96

[degree] C. The heated water then rose

along fissures and faults through the limestone to the surface but lay trapped

beneath impermeable layers of Lias clay until a fault could give access to the

surface. The fault lies beneath

Analysis of the

water’s mineral content has revealed the different kinds of rock through which

it has passed. “There are forty-three

minerals in the water; calcium and sulphate are the main dissolved ions; with

sodium and chloride also important. The

water is low in dissolved metals except for iron which causes the orange

staining” (Cunliffe 2).

Figure

2 shows the rain falling on the Mendips hills, then soaking into the

carboniferous lime stones, then

traveling underground toward the fault lines and then finally

resurfacing near the River Avon, which runs through the city of Bath. Although it is a small diagram, it does show

the distance and rocks the water traveled through during its very long journey.

Figure

2 shows the rain falling on the Mendips hills, then soaking into the

carboniferous lime stones, then

traveling underground toward the fault lines and then finally

resurfacing near the River Avon, which runs through the city of Bath. Although it is a small diagram, it does show

the distance and rocks the water traveled through during its very long journey.

First case of healing

Now that we know

where the water came from it is important to understand the reason the Romans

and Celts thought the water from the springs had healing power. The first documented story of the healing

power of the springs in

The young Prince

Bladud [shown in picture 11] having contracted leprosy on his return journey

from a period of study in Athens was confined to a room within the palace of

his father, King Hudibras, lest the disease should spread throughout the Royal

Court. But the headstrong prince,

wearying of his enforced quarantine, escaped and fled the kingdom, taking up

employment as a lowly pig farmer. But,

after a time the pigs also became infected.

So one day he approached the River Avon, herding his pigs down to the

bottom of a steep, wooden valley to forage for acorns.  As

he waited, he noticed a few of them wallowing in a steaming alder swamp not far

from the river bank. He was amazed to

see that when the pigs emerged from the muddy waters their sores had been

healed. Bladud followed their example

and found that he too had been

As

he waited, he noticed a few of them wallowing in a steaming alder swamp not far

from the river bank. He was amazed to

see that when the pigs emerged from the muddy waters their sores had been

healed. Bladud followed their example

and found that he too had been  healed

of his leprosy. The prince was thus able

to return to his father’s court. (Green

15)

healed

of his leprosy. The prince was thus able

to return to his father’s court. (Green

15)

Although

the story has undergone countless revisions and embellishments throughout the

many hundreds of years of its existence.

The above story is the basic of them all.

As we can see, religion and paying

tribute to their gods was very important to the Romans. We took a brief look at the history of

Bibliography

Clark, John. “The mystery of Bladud.” Bath Past.

Crouch,

Cunliffe,

Barry. The Roman Baths at

Green, Kim.

Macdonald,

Fiona. 100 things you should know

about Ancient

Murray, Stephen

J. “Prehistory.” Welcome from Dot to

Domesday.

Rush, Ian. “History 260: History of

The Roman

Baths. Nov. 2002.

Watney, John. Roman

Britain.

Westwood,

Robert. Ancient

Back to Student Project