Block 14 - Environmental History

Part of a stump and the roots a tree that was once here remain visibile.

The pot holes that exist in the asphalt expose a previous concrete pavement surface, not wood or mud.

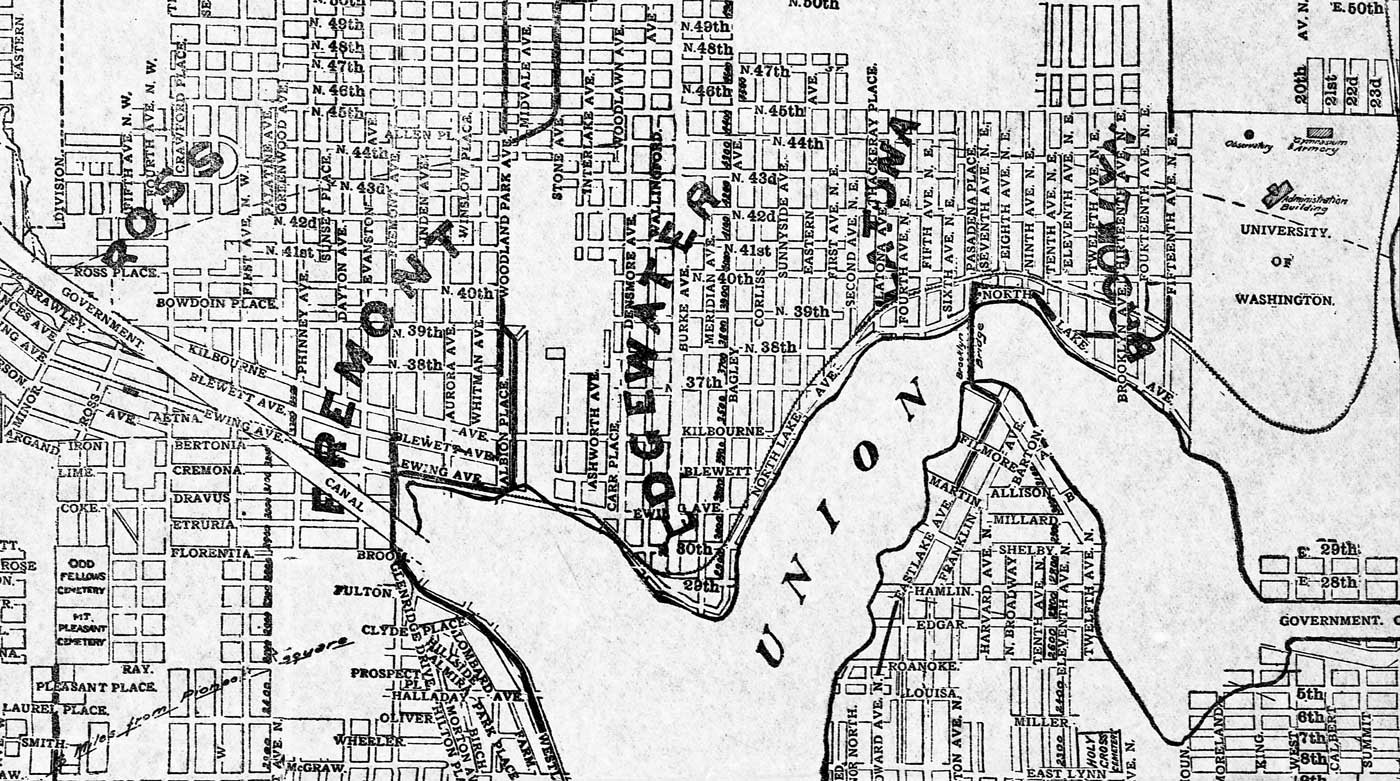

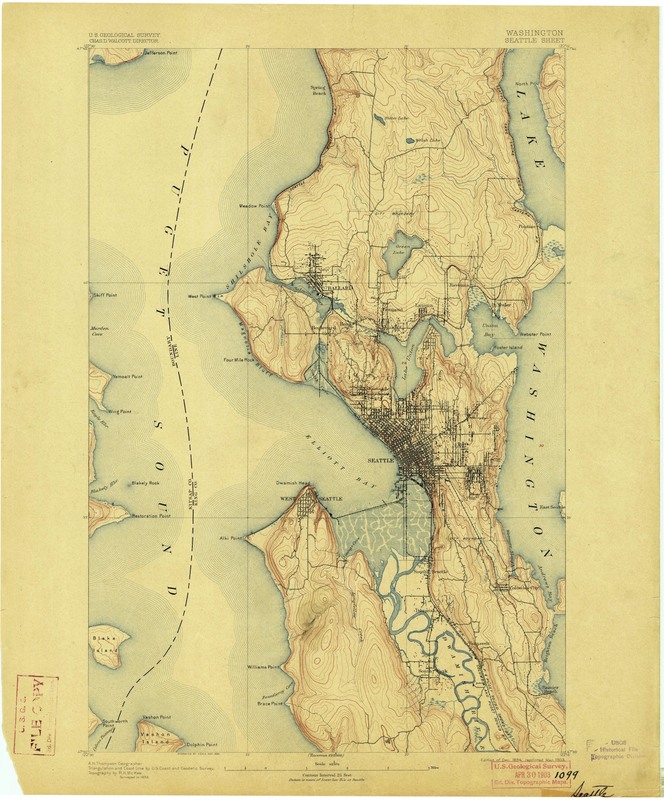

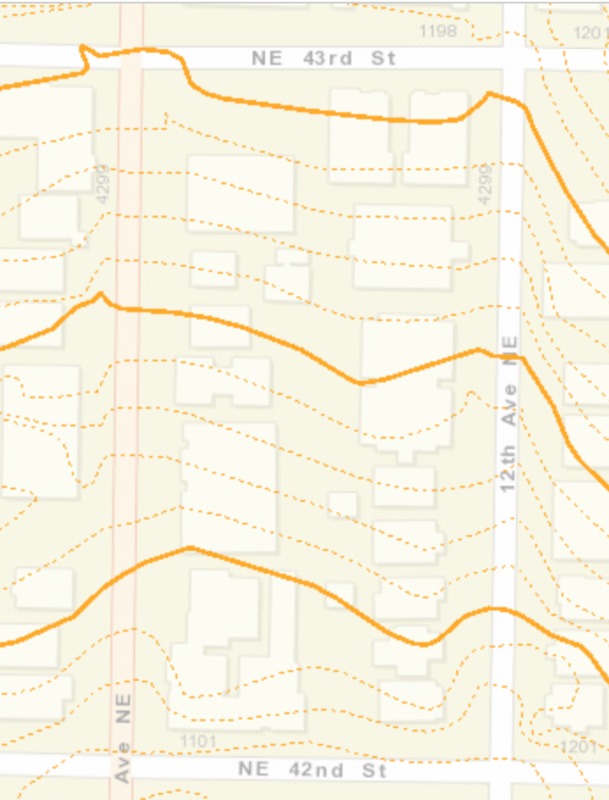

Before European settlements, the area contained lowland forest with massive trees everywhere and a meadow. As described by two of the last indigenous people of the district, the local Coast Salish hunted bear, elk, and deer using snares and spears, and wolves and cougars roamed (Nielsen, p.1). Native blackberries and salmonberries grew and were eaten (p. 2). Since then, no extensive regrading has occurred, but a stream at 45th Street is now only visible in some basements (p. 1). After the United States began occupying the territory, the 173.57 acre lot between 5th and 15th avenues NE and Portage Bay and 45th St, including Block 14, was homesteaded by Christian Brownfield beginning in 1873 (p. 3). Reta Shields, who was born in the U District in 1891, described the area during her childhood as mostly wooded with paths, and as containing a strawberry farm between 12th and Roosevelt (p. 17). The 1894 U.S.G.S map of Seattle shows what appears to be the current Roosevelt Way (ending at 45th St) and University Ave, with sparse houses around them. Between 1900 and 1910 most of the houses that stand were built. The current UW campus was set aside for public school use, remaining as untouched forest through 1885 (p. 7), when real estate developer James Moore platted the Brooklyn Addition. Brooklyn ultimately developed at a slower pace than Ravenna and Latona due to steeper slopes and a slight ridge (p. 8). In 1900, the streets of the District were dirt and mud besides occasional wooden sidewalks, and lacked street lights, sewers, and tap water (p. 20). In 1905, NE 42nd St was “graded and paved.” Current (1993) contour line topographical maps show the streets as clearly a more gradual and steady grade that’s only tilted on one axis compared to within the block, where lines become sporadic and diagonal. The majority of the district was paved with a mix of wooden planks and asphalt for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition of 1909 (p. 30), and some of the plank roads remained until resurfacing after streetcar tracks were removed in 1940 (p. 89). I found no currently existing signs of the muddy and wood-topped streets that once surrounded the same houses. The alleyway is a sea of concrete and asphalt, the streets are asphalt on top of concrete with (presumably) drainage bricks at the edges, the sidewalks are concrete with grass medians containing some trees, and no native ferns seem to exist. Vegetation makes it through cracks in the built environment everywhere, but I cannot be certain what is native to Seattle and what is overgrown American landscaping.