Conclusion

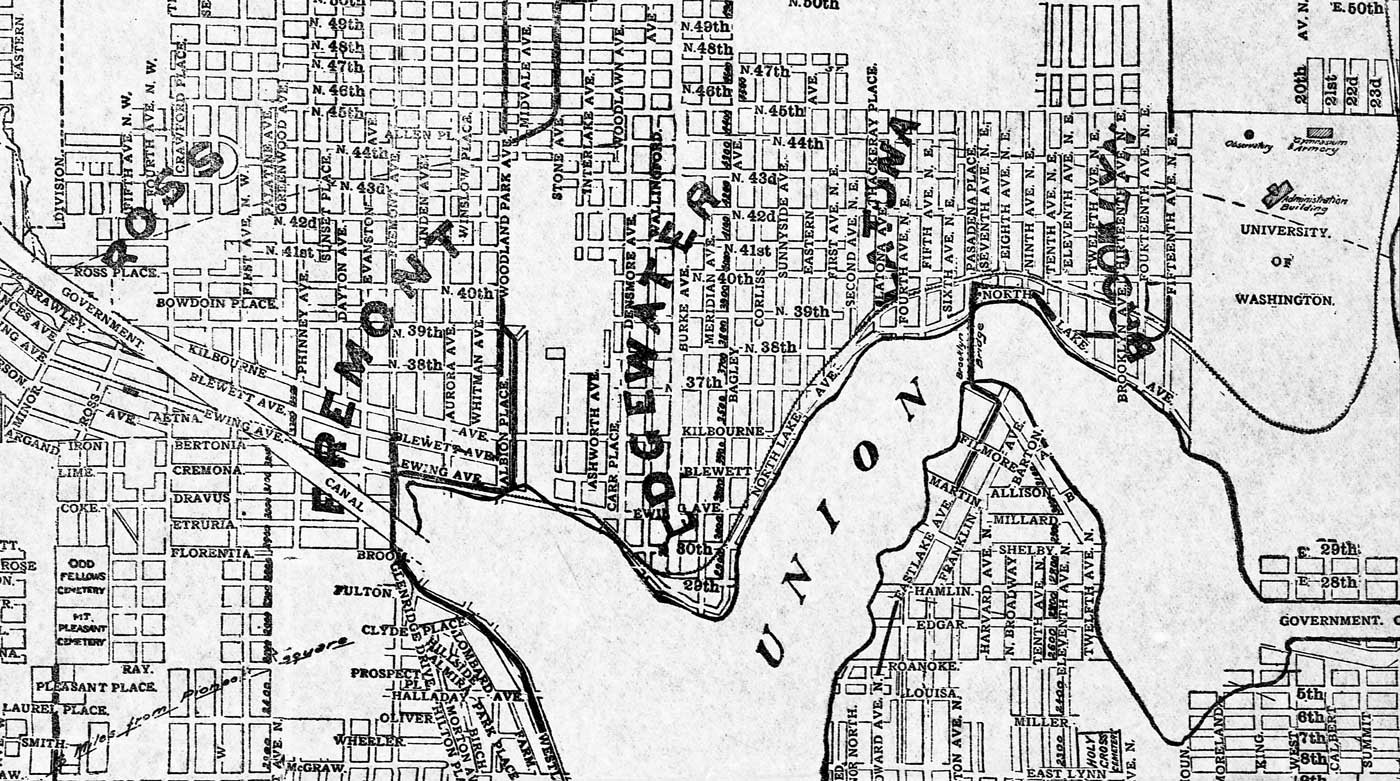

As you find yourself walking south along Brooklyn from the LINK Station of the near future, you may look to your right and see a block covered by apartment buildings. The block between NE 42nd and 41st Avenues, however nondescript it may appear to the urban wanderer, is indeed a living historical artefact, one that traces the urban histories of Seattle, the nation, and the globe in more ways than one. First, you might notice the slope you are walking down at, especially against the underground parking garage under one of the residences; or the few sections of unruly, uncontained natural growth on the block. These facts remind the urban walker that the massive urbanity that they are navigating through is ultimately a human-made, (ostensibly) orderly grid that has been imposed upon a more (ostensibly) chaotic natural world: the city is intimately related to the slopes that were regraded, the trees that were cut down, in order for it to exist. Next, you might notice that the block to your right is entirely residences, and if you need a coffee, or a place to use your laptop, you might want to hop over to the Ave. This seemingly innocuous reality is deeply historical: when the David Denny’s Rainier Power and Railroad Company extended their streetcar line to the University District, it built the line along University Way, rather than along Brooklyn Ave, which real estate developer James Moore had envisioned as the main commercial hub of the neighborhood. Instead, with the increase in traffic from the streetcar line, the Ave would the bustling commercial street that it is today. Thus, the block on Brooklyn Avenue, in the composition of the buildings that occupy its space, can be seen as historically representative of the tight relation between infrastructure development and urban development in the United State. Just as the Transcontinental Railroad of the 19th century accelerated the growth of cities in the West, or the Interstates of 20th century allowed for the growth of suburbs, the early infrastructure development of the U-District, and one decision to develop a streetcar just one block over, had a dramatic effect on the shape of development to come in the U-District. As the LINK expands, historical trends suggest that its opening will transform the U-District. It is quite possible that its opening will drive up property values and rent prices, making the neighborhood less affordable for students and people of low incomes. As the city becomes more and more expensive in general, the U-District, which has long been a residential area for students and people with lower incomes, will have to face the question of “Whose interests are these neighborhood developments serving?"