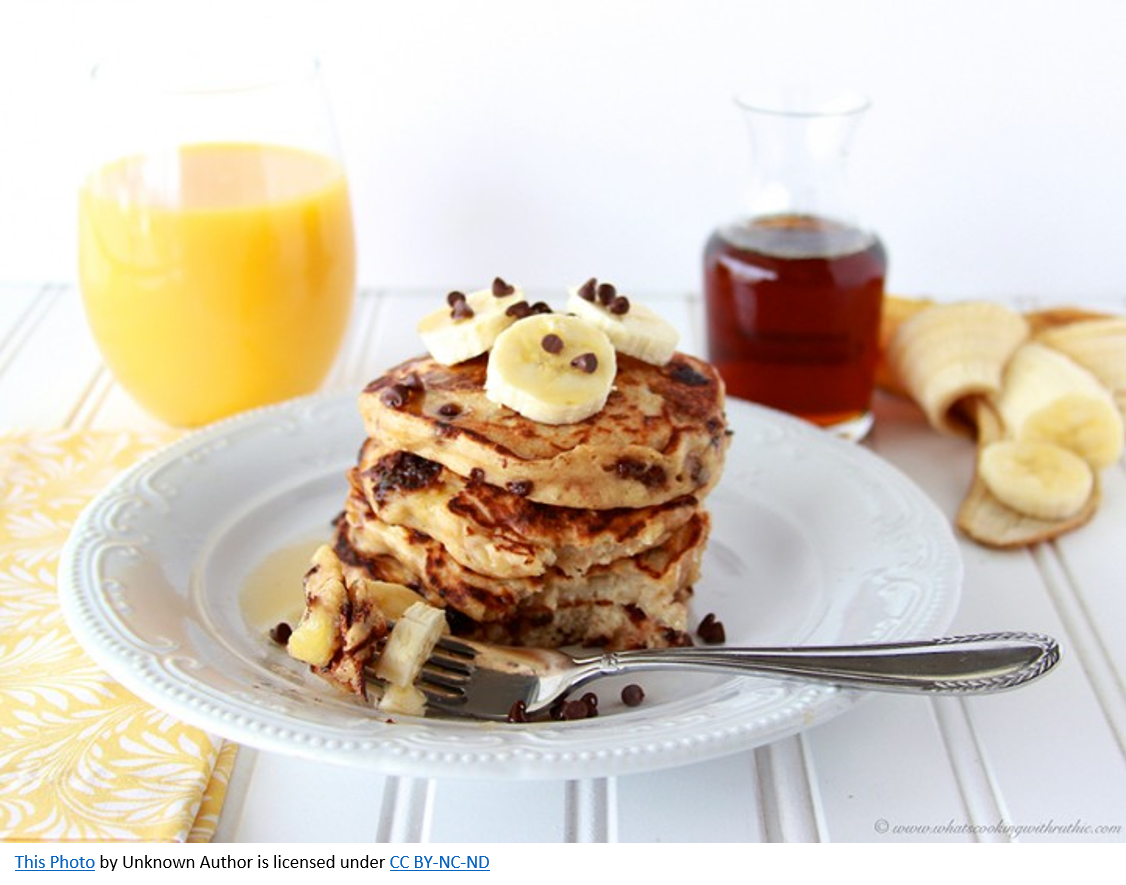

My breakfast this morning was made possible by globalization. Banana chocolate chip pancakes are a standard at my local diner, so it can be hard to imagine a time when they were considered exotic, with their Ecuadorian bananas and chocolate chips made from ingredients sourced in the Ivory Coast. But transcending the limits of local climes and growing seasons, global trade offers me a diverse diet year-round that contributes to both health, pleasure, and perceived quality-of-life.

My breakfast this morning was made possible by globalization. Banana chocolate chip pancakes are a standard at my local diner, so it can be hard to imagine a time when they were considered exotic, with their Ecuadorian bananas and chocolate chips made from ingredients sourced in the Ivory Coast. But transcending the limits of local climes and growing seasons, global trade offers me a diverse diet year-round that contributes to both health, pleasure, and perceived quality-of-life.

But what if I told you I actually employ a kid who harvests my bananas for me? She’s ten years old and works twelve hours each day (Pier, 2002). So industrious. But that’s nothing compared to the seven-year-old machete-handlers who gather the cocoa beans for my chocolate chips. Thanks to child trafficking and forced labor, I don’t pay them a thing (United States Department of Labor, 2016). You might say it sounds a little like slavery. You might be right.

In The Real Cost of Cheap Food, Michael Carolan outlines the ways in which free trade is a system governed by “equal rules for unequal players.” (Carolan, 2011). He details how corporations wield power to grab land and extract resources at unreasonably low prices, creating engines for poverty, human rights abuse, conflict, and even terrorism. All to deliver the low prices we expect in our supermarkets and restaurants.

One has to ask why, as Americans who condemn our nation’s history of slavery, do we look the other way when it comes to our modern economy?

Perhaps it’s the complexity. In the face of tangled commodity chains and indecipherable trade rules, it’s easy to let the link between our “need” for cheap food and the human abuse it requires to remain hidden. No slaves work in fields outside our windows or in the pristine, beautifully stocked grocery stores we frequent. Rather, families laboring to bring us our food are far from view, in countries we’ll likely never have occasion to visit. But as Peter Singer argues (Singer, 2009), distance does not excuse inaction.

[1] Pier, Carol. (April 2002). Tainted Harvest: Child Labor and Obstacles to Organizing on Ecuador’s Banana Plantations. Human Rights Watch. Retrieved from https://www.hrw.org/reports/2002/ecuador/2002ecuador.pdf

[2] United States Department of Labor. (2016). Child Labor and Forced Labor Reports: Côte d’Ivoire. Retrieved from https://www.dol.gov/agencies/ilab/resources/reports/child-labor/côte-dIvoire

[3] Carolan, Michael. (2011). The Real Cost of Cheap Food. Chapter 3. New York: Earthscan.

[4] Singer, Peter. (2009). The Life You Can Save. New York: Random House.

You make some excellent points about the disconnect between Western consumers and the realities of labor in in origin countries. True, we don’t see firsthand the slave and child labor that brings some of our favorite foods to the table – essentially, we’ve outsourced slavery to the developing world. Many Americans seem to be similarly unconcerned with global labor conditions in other industries, like textiles and manufacturing. Cheap food and “fast fashion” go hand-in-hand in a consumption-obsessed society. Sweatshops are another consequence of globalization, as producers must race to be the cheapest and most efficient to compete. I remember when outrage over sweatshop conditions reached a crescendo in the 1990s as the issue gained national media attention – but the same practices still dominate the industry 20+ years later. As you suggest, the complexity of global trade and commodity chains makes it easy for consumers to maintain ignorance, willful or not.

Thank you for your though provoking post. I agree with you that this is a very complex issue, and I think a big part of it is the distance. In another course we learned about some of the barriers to change, as describes by Stoknes, they are the following: doom, distance, denial, iDentity and dissonance. In the food system, all these factors have an impact, but especially distance. First off, people in the States are no longer farmers (at least a huge majority isn’t)! We have become disconnected from our food, the work it takes to grow and harvest, the preparation processes, the slaughter of animals, and even now, with the fast food systems, we have been disconnected from the cooking process. Distance does not excuse inaction, so we must employ mechanisms of communication to reach the mass populations because without a mass shift in public demand, how can we see change?