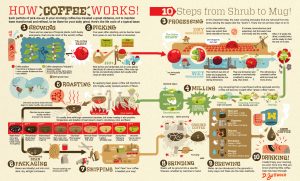

These are the different roasts that can result from the roasting process.

Working as a barista for four years has made coffee an integral part of my life. I drink up to three cups per day, am knowledgeable about different roasts, and smell like it consistently. However, I haven’t taken the time to explore where coffee beans originate from or how they are processed, even when the information is easily accessible. Instead, I get caught-up in my inherent “need” for caffeine or how I can quickly explain fundamental characteristics of a certain roast to a customer. Being busy has prevented me from taking the time to reflect on the underlying processes that coffee beans undergo to reach my mug every morning.

This became especially relevant when engaging in contemplative practices this quarter because I had to stop and take a few minutes to think about my relationship to food. The most impactful practice for me was examining the production of raisins, both by hand and machine. Harvesting raisins is labor and time intensive, and in order to increase efficiency, heavy machinery is primarily used. This reveals that something as simple as a dried grape can be an industrialized food, which ultimately helped me see the long food chain that extends from a raisin in my hand to a farm in California.

Now, when I order coffee, I’ve been more curious about where the coffee beans are sourced and how they are processed. Similar to the raisin, I’ve found that harvesting coffee berries and producing the beans is also labor-intensive, with machinery being a dominant actor at every stage. Not only does this reveal that coffee is industrialized, but also how aspects like waste, oil, and virtual water are incorporated within the chain. Using contemplative practices has been useful in thinking about the negative and positive spillover effects of food and has allowed me to examine my own consumption in more depth.

As a fellow coffee lover, I definitely related to this post. I think coffee has really turned into an on-the-go sort of activity nowadays, which is incredibly convenient but also further encourages people to not know or care where their coffee really came from. I would be interested to see what it would take to get the average coffee-drinker to care about where their coffee was sourced. I thought the infographic you used was really cool and informative, do you think that publicizing this information on a mass scale will make people care about it more? Or are they bound to ignore it because of its inconvenience? As an environmental studies major, one of the biggest issues that I’ve had to tackle was getting people to care about the environment; I wonder if this sort of information will ever make a relevant difference or if it’s bound to just be out there for people to know but not care about.

Iris, I love that you connected the contemplative practice on raisins to coffee. Similar to you, drinking coffee is an essential part of my day. To think of the journey of the coffee bean in place of the raisin is a much more intimate contemplative practice for me. You discuss industrialization of coffee production, and it is interesting to think how distant we are from the process that creates something that feels so close and integral to our everyday lives. Aside from taking the time to contemplate coffee and its greater role in our world’s economic, social, and environmental systems, do you think that we, as coffee drinkers, have a responsibility to reform the industrialized production of coffee? Being aware is certainly an important first step, but is there more that we should do?

Response 2

I really liked the diagram you included at the end of your post; it really helps identify the basics of what goes into the coffee I quickly grab before class. I’d be curious to see a similar diagram, with the proportion of the final cost to consumers that each step amounts to; as we’ve seen in other cases, most of the cost is not from the people growing the coffee in the first place, so breaking down where the costs actually come into play would seem like a good way better put those costs (and the distribution thereof) in context.

I am definitely of the same opinion when it comes to not thinking much about where my food comes from. I’ve been too occupied with research, work, and college to even have time to think and many people in this class and at University of Washington in general can probably relate to this. In addition to being busy, many people most likely don’t want to think about where their food comes from because of the possible negative practices they might find out. This form of complacency enables the continuation of these negative practices and farmers in third world countries are suffering because of it. Furthermore, what happens when we do find out negative practices that occur with the foods we eat? Would most of us attempt to change where we eat or are these eating habits too engrained in our lifestyle to change. This class has really been an eye opener for the negative practices happening in the food industry and we must not be complacent with these negative practices. Every time we go to the coffee shop or even the grocery store, we should thinking about where our food comes from and if any negative practices are associated with the production or transportation of this product. Lastly, we need to think about how to change what we eat and how to encourage others to collectively act upon this.