On Thursday May 24th, the five of us (Angelina, Chloe, Bailey, Rori, and myself) talked with students, faculty, and passerby in front of over two-hundred and fifty cups strung and swinging in the light breeze. The cups were an overwhelming visual, and the DUB Street burger centered underneath our installation provided a tempting smell for dogs straining on their leashes.

May 24th 2018, Picture taken by Mathieu Dubeau

We centered our project on the water footprint of an average hamburger. A shocking four hundred and fifty gallons of water is used in the production of a quarter pound beef patty, compared to under ten gallons for the same amount of vegetables (UNESCO-IHE Institute for Water Education). In our discussions with students and detailed in our pamphlets, we explained how seventy percent of global freshwater is used for agriculture, and how a majority (up to eighty percent) of global corn production is used to feed livestock like cows and chickens (lecture, 4/24). The importance of this discussion centered around the value of virtual water in the context of water shortages. The UN estimates global freshwater demand will exceed supply by over forty percent in 2030. Despite this, fast food burgers are commonly priced below five dollars, failing to reflect in economic terms how demand for meat is outpacing our global resource supply. For this project, virtual water was our entryway into a discussion of how cheap meat, and the ubiquity of fast food burgers on every block, is fundamentally political.

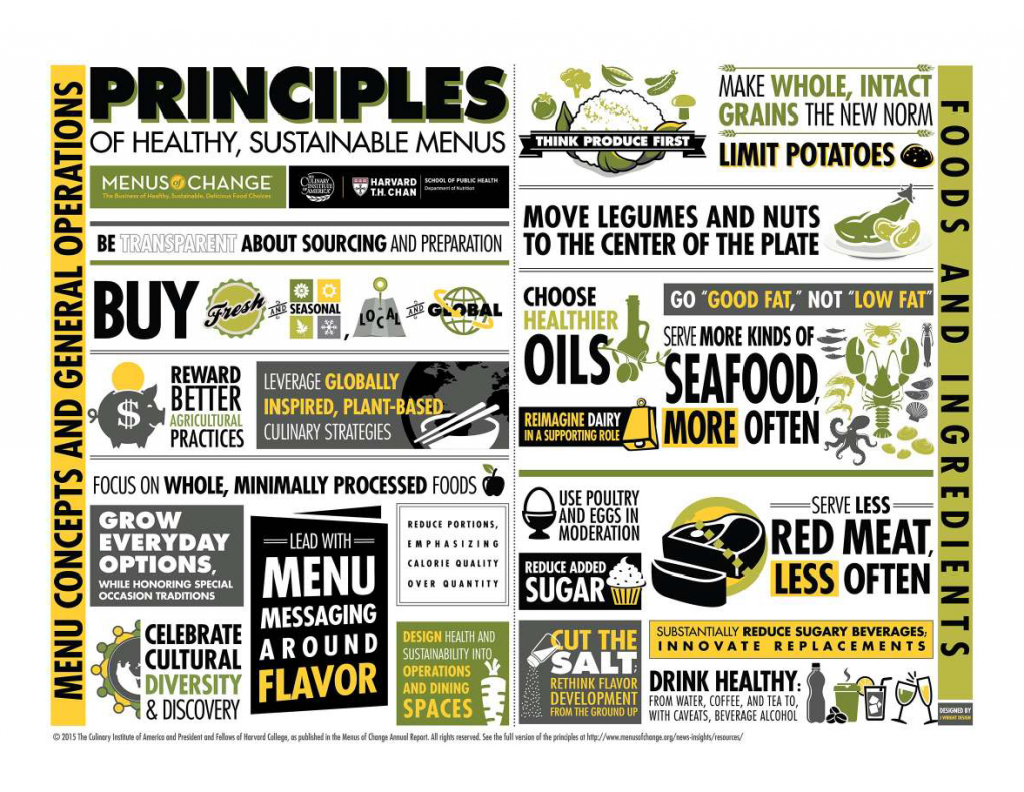

Giulia Szanyi, writer for UW newspaper The Daily, gauged public reaction and wrote, “Students who stopped to interact with the installation and learn what it was about were shocked by the facts they were presented with, and most agreed they needed to change their eating habits.” However, this sentence in The Daily article questions if we successfully delivered the problem of meat as political, not just individual. In his critique of the beloved environmental message of The Lorax, Michael Maniates points out, “When responsibility for environmental problems is individualized, there is little room to ponder institutions, the nature and exercise of political power, or ways of collectively changing the distribution of power and influence in society—to, in other words, think institutionally” (Maniates, 33). However, my group and I were lucky to have stopped Clive, a UW HFS director, who has institutional power to influence what options are available to UW students. He explained, UW is participates in the national Meals for Change initiative, which features “dishes based on a plant-forward food philosophy, a creative cuisine with the accent on fruits, vegetables, whole grains, beans, legumes, soy foods, nuts, seeds, plant oils, herbs and spices” (UW HFS Services). Our project was a reminder that UW students are passionate about sustainable food options and the experience has better prepared us to advocate for such options in the future.